The Sun Also Rises: Miyazaki, Oshima and the Politics of History

- published

- 8 May 2014

Recent years in the Japanese film industry paint a decidedly mixed picture: at first glance, Departures win at the 2008 US Academy Awards and the continuing presence of Takashi Miike, Sion Sono, Hirokazu Koreeda, and others might suggest a healthy and vibrant industry. Behind the spotlight, however, lurks hints of rot. Most recent film statistics suggest an expanding array of films competing for fewer screen hours, and thus less box office tickets. Those films which perform well take an overwhelming percentage of the box office, and leave little else for the rest of the industry. Blockbusters dominate the domestic market, while outside of the aforementioned directors, only a few others manage success abroad.

The Eternal Zero

While Japanese film has made less news, recent political crises have been hitting international newspapers. Now that the LDP has been dominating national politics with a new economic strategy, prime minister Shinzo Abe has found a way to sneak in his extreme right-wing brand of politics into official policy. He has been able to shift the conversation back to that of the early 2000s, when politicians routinely denied Japan’s actions in WWII, blamed foreign powers for the nation’s troubles, and sought to remake Japan in a repeat of its militarist past based on faulty logic.

Yes, faulty logic, one which whitewashes the nuances of Japanese history. That much is obvious, and the international press has pushed back against a number of Abe’s appointees for their most blatant "mistakes." But driving the statements of these politicians is a misunderstanding threatening Japanese society, and a misunderstanding that is not new.

Rather, it is a misunderstanding that has been present since after the war, a repeat of a conversation which occurred sixty years ago, pressed by one filmmaker: Nagisa Oshima. His films from that period provide insight to the present day, both in the film industry, and Japanese society as a whole, about conservative ideas, which fail to allow new ideas and healthy creative expression, in film production, political discussion, and beyond.

Nagisa Oshima and the Politics of History

Fifty years ago, Nagisa Oshima was on the vanguard of a political Japanese cinema: one firmly left-wing, speaking to various economic and social issues still left unresolved after World War II. While not the only director to give a cinematic voice to these issues, Oshima was certainly one of the loudest, and most pointed.

At times contradictory, hyperbolic, aggrandizing, or all of the above at once, Oshima nonetheless had a vision of a Japan clear of its traditional shackles, with a fair and equal society for its oppressed and forgotten lower classes. These ideals come through most clearly in his 1960s films, which touch upon the influence of Japanese history - ancient and modern - in the contemporary era.

Nowhere else in Oshima’s film history is this meeting of history and "now" more prominent than in A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs (Nihon Shunka-ko, 1967). Set within the environment of the political turmoil of 1960s Japan, A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs connects the politics of the time with Japanese colonial history and foundation myths of both Japan and Korea, most definitively by its position in time: the film takes place on National Foundation Day, revering the "official" history of the Japanese nation, in a period where the Japanese state was economically engaged in the Vietnam War - a mixing of historical and contemporary narratives driving the composition of "Japan."

Bawdy Songs shows how these histories can be forgotten and repeated, with disastrous consequences for those at the nation’s margins: namely, the film’s main characters, two high school students named Nakamura and Sachiko (played by Ichiro Araki and Hideko Yoshida).

The two begin the film having just finished taking university entrance examinations in a big city, away from their rural hometown - Sachiko at one college, Nakamura at another, with his three male friends. These four boys are less interested in the exam than in a female student in their examination room, a woman whose name none of them know, just her seat number: 469. Their interest is nothing romantic: they all want to sleep with her, even if it means taking her by force. As they flesh out their fantasies, they go for post-exam celebratory drinks with several of their female classmates (who they also attempt to sleep with) and their teacher Otake (Juzo Itami).

While they go out to drink, Otake teaches them a bawdy folk song, sung from a man’s perspective, about sleeping with various village girls. At one point, he also describes a vast series of traditional folk songs, covering virtually the entire Japanese archipelago, including Okinawa (controlled by America at the time of the film).

What we have in the bawdy songs of Bawdy Songs is, above all, "history." This is not official Japanese history, or even Asian history. Instead, it is a people’s history, or even histories, with all of their horrible contradictions and mythologies. And for each history, we have a song, described by the old leftist high school teacher Otake as "the suppressed voices of the people."

The song Otake teaches to his students, and its subsequent significance of a suppressed voice, function as a twisted rallying cry for them - the four boys at the center of the film, aimless and disaffected, and implied to be from a poorer background, use it to justify their violent sexual desires. The song, describing ways to have sex with local girls, gives the boys a path towards conquest, control over something.

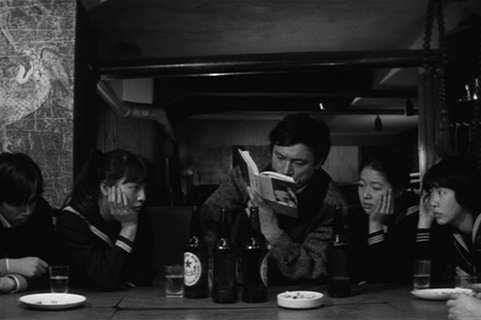

A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs

On its own, the song is interesting and even a little catchy - but when contrasted with the second folk song of the film it takes on a whole new meaning. This second folk song is sung by one of Otake’s students, Sachiko. Sung from the perspective of a World War II-era prostitute working in colonial Manchuria and with a Korean accent – that Sachiko knows this song identifies her history as a zainichi Korean and as the child of a repressed sex slave from the former Japanese empire. Sachiko, like the four boys, sings her own history.

But Sachiko’s song is different from the boys’ song in the sense that it does not justify further violence and oppression. The boys sing the song as they imagine raping their fellow students, and the film itself follows them through it, as Oshima inserts shots of the girls being grabbed, of 469 being thrown onto the table and undressed - their bawdy song drives the framing of the film.

Sachiko’s song is different in that it stops the film: the first time she sings, there are no cutaways, and the camera lingers back and follows her slow walk in a profile shot, keeping her grounded in her environment. Maybe the hope is that the words settle in, and the boys reflect. This happens, once, where after Sachiko sings to Nakamura he acknowledges a violence within him. But this is a fleeting development, and when Sachiko sings again at a peace rally protesting the Vietnam War - her male audience, hearing it, carries her away and, as is heavily implied, rapes her.

Her song represents Japanese historical violence, and her song is greeted with ignorance and celebratory violence of a sort which the boys’ reappropriated folk song comes to represent. Essentially, what happens for the boys, and Nakamura in particular, is a willful forgetting of Japanese history to serve their selfish ends.

And Sachiko herself, by the end of the film, is a silent reminder of what this violence entails. For the last third of the film, she is always present, saying almost nothing, but always there, floating in the background. And as the other characters debate and discuss the meaning of Japanese history - as both a sibling and a violator of its neighbors, Sachiko remains, a living link to that history. And so she watches as Nakamura commits violence and murders the classmate he lusted after, 469, as both her and Nakamura descend, repeating the violence of the previous generation.

"History is in Front of Us; the Future is Behind"[ 1 ]

But what does a pair of high schoolers in a long-forgotten so-called "nuberu-bagu" movie have to do with contemporary cinema, never mind contemporary politics? The lessons of their mistakes, as it turns out, have significant presence in current discussions. To better understand, we must turn to a contemporary filmmaker, one of the few major figures in Japan still engaged with politics of the sort Oshima championed.

Hayao Miyazaki, the celebrated animation director, may not seem like a successor to Oshima; what both share, however, is a keen sense of history and its place in the contemporary social scene. And while Oshima directed as more of a firebrand who had, at times, used his films to lecture about the failures of Japan, Miyazaki has focused on fantasy films, sometimes using abstracted settings to portray important environmental themes. But Miyazaki has rarely been outwardly political, and his films reflect this, without clear answers for difficult questions.

Miyazaki takes the same critical eye towards history and uses it to look at a historical figure in The Wind Rises (Kaze Tachinu, 2013), chronicling the designer of the WWII Zero fighter plane, Jiro Horikoshi. Miyazaki imbues the character with an creative, obsessive imagination and love of the skies; so similar were these qualities to his previous films that one wonders if the spirit of the film isn’t autobiographical in nature.

But the film is not autobiographical, and Horikoshi does, at times, brush up against the politics of the times. Horikoshi, with his colleagues, treats WWII as an unnecessary burden placed upon their designs. Near the end of the film, he even imagines the apocalyptic results of his success, as the burnt wreckage of bombings and downed fighters lingers in his mind.

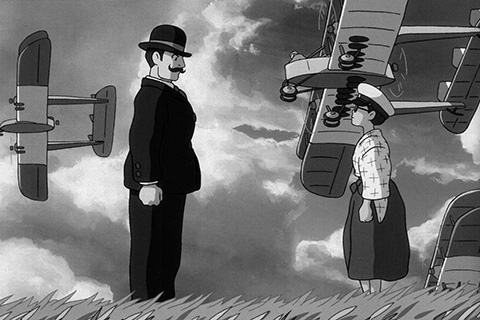

The Wind Rises

The Wind Rises does not preach its anti-war message; instead, the film treats the war as a circumstance greater than any individual, swallowing Horikoshi in a chasm so vast it is almost (almost!) invisible within the film. But the film is also not a direct criticism of Japanese politics, contemporary or historical, because it is a celebration of an individual talent, and an individual creativity. Whatever politics exist in this film’s world serve the character, not the other way around.

At this point, a comparison between Bawdy Songs and The Wind Rises is pertinent, as both films are ultimately about victims and violence. Horikoshi, like Nakamura, is a tragic figure: both are victims of a vast, creeping political violence which forces them into literal violence. Horikoshi, to an extent, recognizes and is haunted by the consequences of his actions. Nakamura, on the other hand, is too young, too naive, and, strangely enough, too cynical to know better. While Horikoshi has dreams and ambitions, Nakamura has none, because he has never had the chance to have them. Why behave rationally when both past and present have been left blank?

This is where these films draw us to the present day, and the era of Abenomics.

Miyazaki and the Conservative Film Industry

Around the same time The Wind Rises was released in Japan, Studio Ghibli published in their monthly magazine Neppu an essay by Miyazaki, detailing his views on contemporary Japanese politics, most particularly his fervent opposition to contemporary right-wing views of wartime history.[ 2 ] What is interesting in this article, however, is Miyazaki’s humility, specifically in how he relates his time as a small child in WWII.

"If I had been born just a bit earlier, without doubt, I would have been a fervent gunkoku shonen. What’s more, had I been born just a bit earlier, I would have signed up to fight and die on the battlefield. [...] For better or worse, had they rejected me over my poor eyesight, I would have probably signed up to draw propaganda comics."[ 3 ]

The Wind Rises

Miyazaki describes the seductive power of the nationalist movement, even as he recognizes it now (and recognized it after the war) as a dangerous current, which would severely damage the nation’s reputation abroad, and its own citizens. And this nationalist movement requires a forgetting of history - a denial of comfort women and a rejection of Japan’s neighbors - in order to succeed. Miyazaki recognizes that, in creating a conservative, propagandistic country in this image, Japan cannot function on the international stage. But so be it.

But how does this relate to the film industry? There seems to be a trend of stagnation underpinning the issues in both politics and film. As mentioned at the beginning of this essay, the Japanese film industry has been stagnating of late. The numbers suggest not much movement: slightly increasing attendance with slightly decreasing revenue.

What is more concerning is the concentration of revenue at the top: in 2013, 69% of ticket receipts went to the top 35 domestic films, compared with 60% for the United States.[ 4 ] At first, this difference may not sound like much, but Japan is then splitting the last 31% amongst a much wider array of releases: 1117 in 2013, of which 591 films are domestically produced. This number is almost double the 683 releases in the US. So there is a tremendous imbalance in releases in Japan, where the highest-grossing films dominate the industry and leave other companies, including all independent releases, with table scraps.

Major companies dominating the industry would be tolerable if the system promoted creative cinema. As director Lee Sang-il states, however, the large companies are "becoming very conservative, because the investor wants a guarantee that they can sell the film to television, for example. Otherwise, the risk is too much for them. If there is something that I really want to do that is outside of that, then it can only be on a very low budget."[ 5 ] And when the film is made on a low budget, outside of the conservative system, the options for release, and for wider viewing, become even more difficult.

Top blockbusters, meanwhile, mostly represent manga and light novel adaptations, or film versions of anime TV, similar to the entertainment at the top of the US box office. For the most part, openly right-wing revisionist films have been uncommon in Japanese cinema. Until this year, in fact, one could comfortably call them a niche business - except that now, one of the highest-grossing films of 2014 is The Eternal Zero (Eien no 0, 2014), a very different take on the same Zero fighter plane seen in The Wind Rises.

In this film, the young male protagonist finds out about his dead grandfather, who overcame a timid personality to die as a kamikaze pilot in a blaze of glory during the war in the Pacific. This plot is not particularly noteworthy or interesting, and similar stories have been playing in the theater in Yasukuni’s history museum of years, to little fanfare. That the film is now breaking box office records for live-action films is, however, noteworthy.[ 6 ]

At this time, twenty years after the collapse of the bubble economy and Japan continuing to sink into economic irrelevance, maybe this is where the story provides a sense of comfort for Japanese youth. Roland Kelts quotes Susan Napier as describing this period as a moment when Abenomics has finally provided a chance for "radical changes." She then comments that, "I think people are both hopeful and scared to hope."[ 7 ] And I think this is useful in considering Nakamura in Bawdy Songs, who is unable to hope and forced into violence. The Eternal Zero, on the other hand, posits a hopeful young man, except that he, like Nakamura, is bathed in lies about his own history, unable to hear the truth.

The Eternal Zero

But what is also very important about The Eternal Zero is that its original author, Naoki Hyakuta, is now a governor of national broadcaster NHK. Hyakuta has repeatedly stated historically inaccurate views of World War II, consistent with those of the new NHK chairman Momii Katsuo. Both men were appointed by PM Abe, and represent a new direction for NHK, where its politically neutral stance appears under threat.[ 8 ]

Similarly, the presence of The Eternal Zero could suggest a new direction for the film industry, but one away from the requests by Lee Sang-il, away from an opening to new talent, and towards an industry whose creative structures toe the conservative political line.

Conservative Film Business and Conservative Politics

The failures of the Japanese film industry to foster new and creative talent would, on its own, not be so notable, were this affliction of conservatism not so obvious throughout other business sectors in Japan.

It’s difficult to cite specific examples of an insular, conservative business culture; a simple overview of the 2011 Olympus scandal, however, provides a potent example. The company’s newly-installed British CEO, Michael Woodford, was fired after two weeks on the job after discovering massive corruption. What makes this scandal so absurd, however, is that Woodford had to speak to the foreign press about Olympus’s decades-long coverup of financial losses before the issue captured the attention of any major Japanese newspaper.[ 9 ]

Woodford represented an attempt to reinvent a company in an "international" image, even when that company was not prepared for a reinvention.[ 10 ] And when he tried to hold the organization accountable, he was faced with a press equally unprepared.

A business world unable to handle outside views plays into hiring practices: a 2012 report concluded that only 20 percent of companies in Japan would consider hiring college graduates with study-abroad experience.[ 11 ] It is not so surprising, then, that Japanese youth are studying abroad in far fewer numbers, as a Japan Times article notes[ 12 ] - and rightly points the blame at conservative business practices, rather than the mindset of Japanese youth.

To say that a rigid, bloated film industry, corrupt business practices, and diminishing study abroad prospects are all connected may seem absurd. But a common thread emerges throughout: a structural conservatism, one which calcifies industry practices, and disallows new and creative ideas to flourish. This path leads to business disaster, as the Olympus scandal shows.

An economy bent on hiding new ideas, and pushing out the facts. Here, we see this thread of conservatism leading us to Abe, and to Miyazaki’s criticism of our current government. In one place, we have structural and economic conservatism leading to creative stagnation; on the other, a political conservatism leading to yet more creative stagnation. The appointments of Hyakuta and Momii at NHK suggest a rot crossing industry lines.

Already, as The Eternal Zero tops the box office, anti-Korean/Chinese books have begun topping the bestsellers lists.[ 13 ] And with Abe’s clear intentions to make Japanese education more “patriotic” how long before Japanese youth begin accepting this distorted history as fact? The Economist has already picked up on the trend, connecting The Eternal Zero’s box office record with a recent Tokyo gubenatorial election; the Hyakuta-backed candidate, Tamogami Toshio, captured an above-average percentage of the youth vote (one in four) suggesting a new, "patriotic," Japanese youth.[ 14 ]

These "patriotic" youth do not allow for much room in expression; reactions online to The Wind Rises from right-wing trolls, for example, called Miyazaki "a traitor" and asked (sarcastically) if he would pay comfort women with his profits. In moments like this, one thinks of Nakamura in Bawdy Songs, ignorant of history to the point of violence.

Another Direction, and a Return to Oshima

It is not simply Nakamura’s descent into violence which still echoes into today. Sachiko, in almost literal terms, still represents today the failure of the Japanese government to re-acknowledge its colonial-era war crimes in Korea and China.[ 15 ] She also represents a small window into the rest of the world, a remnant of relations between Japan and abroad, based on real history.

But Sachiko is not simply a cypher for painful history between Japan and its neighbors; she is also an individual, a teenage girl in contemporary Japan who can possibly provide a future to difficult political and social questions - as can Nakamura. She tries to tell Nakamura to stop, even though this falls on deaf ears.

Instead, both are sacrificed for a strange historical game, where the savaging of "the suppressed people," Japanese and Korean alike, is just as sudden and real as the history driving them there. That all this occurs on National Foundation Day only solidifies the extent to which the historical and contemporary violence is a product of the state’s own power structure.

A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs

And that power structure, when unable to welcome new ideas, makes the cries of "stop!" all the harder to hear. Like Sachiko with Nakamura, individuals such as Lee Sang-il with the film world, or Michael Woodford with Olympus, make their cries upon deaf ears, to the detriment of their industries.

How does one fight this? Bawdy Songs may have the answer in its ending. In the final scene, Nakamura is confronted with a story of the origins of the Japanese people, one which claims Japanese and Korean people are the same - a story of shared lineage, and thus suggesting cooperation. Despite hearing this message, one of a shared lineage, Nakamura chooses to act in violence, killing his object of desire, 469. And just as she dies, the film ends, right in the midst of its climax - the final shot of the film is a closeup of 469’s face with Nakamura’s hands on her neck, so we cannot even see his reaction to her death.

Bawdy Songs has no conclusion; instead, the viewer leaves the theatre (or turns off the DVD) without knowledge of what happens to Nakamura, having chosen to act out in violence without direction - or, for that matter, to his victim 469, or to Sachiko. No one can speculate what each viewer of the film chooses, but there seems to be a strong notion towards a call to action. An older generation has failed to educate its youth on the dangers of war, of history, and of their neighbors. Maybe Oshima hoped that, after the failures of World War II and the Vietnam War, we would do better. Hence the impression of a call to action: learn from Sachiko’s life, and not to repeat Nakamura’s mistakes.

On the other hand, the film is now almost fifty years old, and Oshima has been dead for over a year. The film’s message, despite its pertinency even today, is now part of the same history it depicts.

Perhaps we can turn to Miyazaki. In his Neppu essay, Miyazaki explains his ideal vision of Japan, free of nuclear power, right wing militarists, and a whole lot else. As Matthew Penney summarizes, "he outlines a vision of a Japan with a population of around thirty million with an economy that has been de-nuclearized and promotes shared prosperity, grounded understanding of how goods make it from farm, field, or factory to a consumer’s hands, and environmental sustainability. If a market for animation no longer exists in such a country, Miyazaki adds, so be it."[ 16 ]

One of the most appealing aspects of Miyazaki’s vision of a future Japan is how well it would fit with a society that learned the lessons of Bawdy Songs, one which apologizes for history and engages in peaceful coexistence with its surroundings. One also wonders that, should the government continue to alienate its allies and neighbors, and Japanese businesses continue to calcify culturally and structurally, wouldn’t Japan as a cultural and economic giant decline in the direction of Miyazaki’s vision?

Either way, such a transition would not be easy or without painful sacrifice. But what is inspiring about both Oshima of the 1960s and Miyazaki today is their vision of a Japanese nation without the harmful history built on lies and deceit: essentially, honesty in creative practices, something the Japanese film industry needs today.

References

- [ 1 ]. This quotation is by Yoshie Hotta, used by Miyazaki in his essay in the Ghibli magazine Neppu, July 2013.

- [ 2 ]. An English translation of Miyazaki’s essay can be read at Japan Focus: http://japanfocus.org/-Miyazaki-Hayao/4176. The original Japanese can be found here: http://www.ghibli.jp/docs/0718kenpo.pdf

- [ 3 ]. Translation mine.

- [ 4 ]. in 2013, the top 35 films made $6.5 billion USD, of a market worth $10.9 billion. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/yearly/chart/?yr=2013&p=.htm

- [ 5 ]. http://www.filmbiz.asia/news/lee-sang-il-on-the-limits-of-japanese-cinema

- [ 6 ]. http://www.filmbiz.asia/news/eternal-zero-tops-japan-bo-for-8th-week

- [ 7 ]. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2013/10/08/general/backlash-against-miyazaki-is-generational/

- [ 8 ]. http://ajw.asahi.com/article/behind_news/politics/AJ201402040048

- [ 9 ]. http://www.webcitation.org/64XYGLEOv

- [ 10 ]. http://www.webcitation.org/63EIT2stq

- [ 11 ]. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/30/business/global/as-global-rivals-gain-ground-corporate-japan-clings-to-cautious-ways.html?_r=0

- [ 12 ]. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2013/05/21/issues/ambivalent-japan-turns-on-its-insular-youth/

- [ 13 ]. http://ajw.asahi.com/article/behind_news/social_affairs/AJ201402120004

- [ 14 ]. http://www.economist.com/news/asia/21597946-film-about-kamikaze-pilots-gives-worrying-boost-nationalists-mission-accomplished

- [ 15 ]. We can’t forget that Japanese prime ministers have been apologizing for the state’s actions during World War II repeatedly since the 1990s!

- [ 16 ]. http://japanfocus.org/events/view/189