Ayumi Sakamoto

- Published

- 18 August 2014

by Dimitri Ianni

With 591 domestic entries, the year 2013 was a dense one for Japanese cinema, yet one with an arguable decrease in quality. In this environment, first-time director Ayumi Sakamoto (b. 1981) and her debut feature Forma are showing notable promise. The film received the Best Picture Award in the Japanese Cinema Splash section at October 2013’s Tokyo International Film Festival, followed by the FIPRESCI Prize at the 64th Berlinale in early 2014.

The appeal of this sparse psycho-drama shot in a Haneke-like style lies in its minimalist direction composed of lengthy static shots, challenging the viewer to the point of exhaustion, yet ultimately rewarding them with its cold and distanced-framing approach to the real, unveiling little by little, layer after layer of hidden truth and repressed resentments. Probing the dark recesses of our human hearts, Sakamoto's austere and fragmented narrative delivers an intriguing and suspenseful mise-en-abyme, which undoubtedly establishes her as a new voice to follow within the wide-open landscape of new Japanese cinema.

Dimitri Ianni met Ayumi Sakamoto at the 2014 Nippon Connection festival in Frankfurt, Germany, with help from interpreter Mizuki Mazz, with additional translating and editing by Mariko Nouchi.

Could you tell us how you became a film director?

Right after graduating from high school I tried to enter Nihon University College of Art (Nichigei), but unfortunately I failed. There probably could've been other opportunities for me to attend short term art schools to study filmmaking but being from such a remote area as Kumamoto (located on the island of Kyushu), I was only aware of this arts university and didn’t have any alternative. So after that I went job hunting and found work at a studio making commercials. That’s where I met Keisuke Yoshida, who was a lighting technician and collaborator of Shinya Tsukamoto. I was really excited about entering a completely new world, and shortly afterwards Yoshida offered me to join the Tsukamoto team and start working with them. There I learned production and shooting and I became a lighting technician. I assisted him on all his films starting from Lizard (Tokage, 2003) thru Nightmare Detective 2 (2008). Later I crossed paths with Ryo Nishihara, who helped me with scriptwriting and with whom I co-wrote Forma. And eventually I met my producer Fumiyuki Yanaka who became my mentor and helped me enter the film industry and accomplish my debut.

What impressed you most working for Tsukamoto? Was it a decisive experience in wanting to become a director?

I really respect him and I wouldn't be who I am today without his existence. What struck me the most was his sheer passion. The essence of an artist is passion, that's what I learned from him. Though he already created so many movies it never runs out, and he always retains a strong desire for each new creation. I really felt an indefinable aura and energy surrounding him. Of course his directing and writing are great, but it was rather his being than his movies that was a driving force to me. Yet I had already chosen to become a film director when I was a student. Actually what had a decisive impact on my choice was seeing The Key (Kelid, 1987), an Iranian film written by Abbas Kiarostami and directed by Ebrahim Forouzesh. Up 'til then, for me cinema was just mainstream entertainment which I mainly experienced through Hollywood and Shochiku's Tora-san series. But watching The Key changed my perspective on the art of filmmaking. It revealed a new world of expression. It was such a great film, with very little dialogue and a unique setting. Basically the film revolves around a boy looking for a key. There was hardly any drama but at the same time it became so dramatic. So to me small things became more effective in creating drama, which is opposite to mainstream conventions. At the same time since there was no Internet at the time, I didn't have access to a wide range of filmic expressions. So this film became an eye opener and convinced me I could make a film myself.

Let's talk about Forma. How long ago did you start working on the project?

It was about 6 or 7 years ago.

Why did it take you so long?

During the time when I started writing with Nishihara, I was still working as a lighting technician. It was my main job so I didn't really have that much spare time but I already envisioned the idea of Forma, and was constantly thinking about it.

Was it your original idea? How did you collaborate with Nishihara?

Yes, it was my idea. The main flow, like switching the main character during the story or inserting the video sequence at the end, was already there. What I did with Nishihara was discuss the details. We eventually ended up writing 25 versions of the script before the final draft. Though during the process of writing, which took around 4 years, there were times where we didn't even talk to each other because we ran into an argument over some detail. But without his help I wouldn't have been able to complete this movie.

Forma

Did you shoot the movie according to the script or did any changes happen during the shooting?

We followed the shooting script, except for a few parts that I changed. For example the long park scene. There used to be another scene to follow on, but I realized it could actually be shown in the park scene so I integrated them. There were a couple of scenes like that. And actually there was a major change concerning the ending of the movie. In the script the father was supposed to stab Yukari to death in the last scene. But Yanaka my producer doubted its purpose the day before shooting. He didn’t judge it, but he asked me if I was convinced, looking back at all the scenes we had shot so far, thinking about their characters. Was that really what I wanted to convey… I was challenged by his objection and couldn't sleep the whole night before shooting. And I realized what was meaningful wasn't so much that he stabbed her, but how both characters were going to deal with and overcome such a critical situation. So I finally decided to change the ending.

So you decided to leave the final scene more open to interpretation?

Yes, this made more sense. It’s more effective if you let things hang in a suspenseful way. It allows the audience to participate and decide for themselves how things will go on. Movies should stimulate the imagination. Also I decided to change the scene just before the shooting started. The setting was ready and the camera was about to roll. Yukari even had a patch of blood inside her jacket so that she could act the stabbing scene. As I was standing among my actors (Emiko Matsuoka and Ken Mitsuishi) I felt the atmosphere of the set and decided to change the scene and cut it that way. Also the last scene took place on the very last day of shooting. So Nagisa Umeno who plays Ayako was also present for the farewell. And when we decided the change, she was really content with our choice. So it convinced me I had made the right decision. Usually the script dictates shooting, but in the case of Forma it was different. I think the concept of the film, the atmosphere on the set, the condition of the actors at the moment of the shoot, all these elements influenced the film and made these changes happen.

Traditionally a movie is shot in little pieces, not in the consecutive order of the script. How did you shoot and why?

You’re right but we proceeded differently. We planned to shoot the film in sequence. And my producer's idea was that the final scene should be shot last. It was also what I wanted because it provides a better sense of reality to the actors. Action happens in order and they get a sense of time and unfolding of events.

Forma

So your purpose was to achieve realism, to be as close as possible to reality?

Yes I wanted a sense of the real. And also there were no rehearsals during shooting because I wanted to let the chemistry happen between actors. I wanted to let them act freely in order to witness something burst out or unexpected happen from the ordinary reality. I wanted a sense of "realness". My goal was to have reality enter film.

I'm surprised you didn't have any rehearsals, especially considering the length of the scenes which are shot in single takes.

My intention was that the actors shouldn't act but instead become their characters. In order to achieve natural acting we prepared thoroughly before shooting. So in the end we only needed one take to shoot each scene. For example, we only did two takes for the 24-minute warehouse scene, but I eventually ended up using the first one.

Since you didn't rehearse with your actors prior to shooting or on set, how did you achieve such natural performances?

In order to prepare the actors I worked a lot on elaborating the background of each character and their past. For example for Yukari I would write down all the details of her life, like what kind of music she listens to, what was her childhood like, what's her relationship with her friends, what's her family like, how she behaved as a little girl, as a teenager and now as an adult, etc. Or I told the actors, for example, 4 years ago Ayako used to go to a tennis dating circle but she's been sexless for 2 or 3 years. So I gave all these facts and background information to the actors who had them in mind before shooting. That's how they managed to become their own characters and avoid ‘acting’ as characters. And I also created a calendar schedule which spans from January 15th until March 25th which is the actual day the stabbing was meant to occur. So everyone calls it the "killing calendar" as a joke. And on each corresponding day I wrote which scene took place and what happens in the characters' lives. In that way they got a sense of the unfolding of events in real time.

Halfway through the movie when the character of Nagata appears, you decided to break the narrative, introducing multiple points of view, in a Rashomon-like structure.

Actually Nagata was the first character I had in my mind, I started to develop the story from him and he holds many meanings. I wanted to construct the story objectively, not to stick with one main character but with different point of views. So I built the story in a matter-of-fact approach avoiding empathy with any specific character. I chose to break the continuity and mix the scenes up that way because I didn't want the characters to reflect upon their past in a classic flashback device. Instead I wanted to show the actual facts as they were happening and expose the reality of the instant from different perspectives and angles. That's why I chose to edit the film that way. It's a way to describe reality through a more objective perspective.

Besides, another important element of the film is that the father is an editor. His job is to edit the lives of people. So when he suddenly receives the videotape of what happened in the warehouse it becomes an ironic play on his job. The reason why I introduced this irony is that nowadays, in our information society, information is very uncertain: what’s real or fake? We see made-up information everyday and doubtlessly take it for granted. So people who work in the mass media industry, as well as artists, all walk a tightrope about how to present information to the public. I wanted to express how risky and responsible our position is, as well as to caution myself as an artist. So it was also a form of self-critique about how carelessly we creators control information at times.

Avoiding any close-ups also contributes to this objectiveness.

When shooting close-ups, we tend to empathize with the characters and justify their actions. People will feel that through the screen. This is the main reason why I didn’t use any close-ups on faces. Also there are many layers of emotions behind each character, even though these are not expressed in words. Close-ups or camera blocking cuts off all emotions and atmosphere behind them, this is another important reason why I avoided them.

Forma

In film, subjectivity is created through editing, which you refuse to adopt in Forma. So in a way your film stands as a hidden critique of our information society and the status of contemporary images.

Actually the underlying theme of the movie to me was that I always feel something is wrong with the fact that the media detain power to deliver wrong information and change facts.

I also noticed in the movie you included many video screens. Like when Ayako goes into the electronics shop and fiddles with a camera or at her home where the TV set is playing in the background. The presence of those video screens is a hint to this critique.

Yes, that was actually part of the hidden meaning in the film, so I'm glad you noticed it.

I’d like to talk about your influences. The video device that records the murder, the fact that a killing happens off-screen, and also how the father discovers it through a videotape, all these elements reminded me of Haneke’s Benny's Video. Was this film any source of inspiration to you?

I wasn't really inspired by Benny's Video for the videotape murder scene. Actually I watched it along with some of his other movies after Forma’s production had been decided, but I am very influenced by Haneke. I absolutely love his films. Actually there are several nods to his work in Forma, like the tennis scene which was a reference to the ping pong scene in 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance. And in Yukari's room you can see a DVD box set of Haneke.

What do you appreciate about Haneke?

Funny Games was the first movie of his I saw. What I liked about his work is that he hides his true intentions from the audience. The essence of his movies is hidden. Its meaning is never delivered in a clear cut way, his images are very much open to interpretation. In that sense he really inspired me. So in Forma I tried to hide the main theme of the movie and not make it too obvious what the film was really about. I'm concealing it under layers but it still comes out because of its powerful nature.

I also think you both share a certain coldness and distance towards human beings. The way you stare at them.

Yes, I have a similar stare. I tend to look at things happening in the world from a distance. I have an ambivalent feeling. Human beings wage war, kill, hate each other, eat meat. I detest human beings, including myself who’s part of them nonetheless. But on the other hand I love people. So these conflicting emotions nourish my work.

Forma

Are there any other directors which you appreciate?

Angelopoulos and Kieslowski.

I noticed in the editing room when the father is watching a sports report, the commentator calls out one of the participants as Kieslowski.

Yes, that's correct. It was a small homage. I'm really surprised since you're the first one to notice this.

What I found interesting in the mise-en-scène is your use of off-screen. You deliberately downplay any strong emotion by shifting it off-screen, like when Ayako cries at home and you just show a shot of her father staring at her. Or again when Yukari cries after Nagata. You’re trying to suppress all the drama from the screen.

This idea comes from Iranian cinema. Because of the political context and the strong state censorship which afflicts Iranian films there are a lot of explicit acts that you can't show on screen. Like two people kissing, holding hands, someone crying, or a killing... So you have to find a way to express these emotions without showing them. That's what I noticed in the strength of Iranian cinema and tried to appropriate in my own filmmaking.

With Forma you’re making a kind of anti-cinema?

Exactly. Anti-ism against Japanese cinema.

Forma

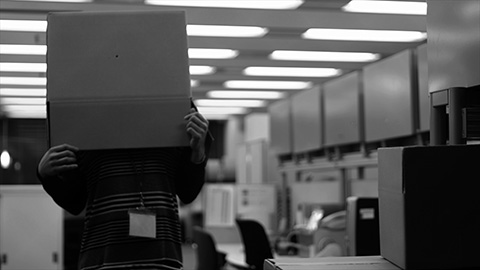

The opening scene when Ayako puts a box on her head is striking. How did you get this idea?

It was actually Nishihara's idea. It was an abstract way of depicting the mental state Ayako's character is going through, all the darkness that she is shrouded in. By wearing this cardboard box she’s suppressing her being, her emotions. She feels like disappearing because she doesn’t like herself, which is mainly driven by hatred and negative emotions, but that's also what keeps her going. And at the end she got suffocated by cardboard that Yukari was pressing onto her face. So it connected both scenes together well and made sense. It also plays as a tribute to Kobo Abe's novel The Box Man (Hako Otoko).

I see Forma more as a conceptual attempt at defining the power of cinema rather than a straight narrative fiction. And the title of the film reinforces this impression. Could you elaborate its meaning?

The title comes from Latin which has several meanings like form, figure or appearance. It also refers to Aristotle's theory of universals: the eidos. But actually there's no direct translation in Japanese, so I used the original word. For me it represents something immutable. If you look back at it, no matter what happens today, it will always exist. So for example, it’s a fact that Ayako was living her life before she died. So even though her body disappeared, the fact that she had an existence in the world is an undeniable fact. That was my interpretation of the meaning of Forma. Even if you can't see a trace or a fact it’s still there in a way because it happened. If you try to translate Forma in Japanese, the closest would be honshitsu [本質], meaning essence or origin. But for me the word has a more mental significance, something spiritual related to the soul.

Last, being French, it was funny for me to notice a shoe box in Ayako’s bedroom with the name ‘cocue’ written on it. Did you know that in French it’s the feminine form of the word for cuckold?

No! Are you joking? That's amazing! [laughs]. You know in Japan it's a very cute brand of women shoes. I didn't know the meaning of the word, but it's like a happy coincidence because actually I was wondering if we shouldn’t have moved it, since it kind of stands out, but I thought Ayako would like that brand. And it happens it was not in Yukari's room, so now I realize it perfectly fits Ayako's character and represents her. So while shooting, if all the crew and cast give their all, they draw little miracles like this to happen.