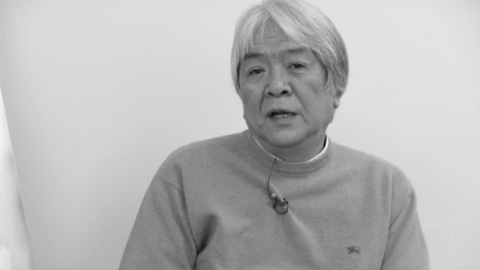

Jun Ichikawa – An Appreciation

- published

- 15 December 2008

Where is the "real Japan"? Haven't Westernization and modernization killed it off for good?

Lafcadio Hearn, the writer best known for explaining the "real Japan" of folklore and legend to the world, asked these questions a century ago and his answers, with some reason, were not encouraging. A Japanese born in 1850 who survived into her eighties would have seen an entire society move from the feudal to the modern era. The sword-carrying samurai of her girlhood gave way, by her old age, to peasant conscripts marching off to conquer Asia with machine guns and tanks.

But core values and beliefs change more slowly than weaponry and, the longer I live in Japan - more than thirty years now and counting - the more I realize that, appearances to the contrary, the "real Japan" is still alive - and is a different place indeed from anywhere else.

Among Japanese directors born after the war, Jun Ichikawa knew that Japan the best, though his one attempt at a period drama, Ryoma's Wife, Her Husband and Her Lover (Ryoma no Tsuma to sono Otto to Aijin, 2000), was also his one big failure.

A common one-word description of his films, especially the ones from his first decade as a director, is jimi - which the dictionary translates as "plain, simple, quiet, modest." His heroes, from Yasuko Tomita's sullen, stubbornly determined school girl in Bu*Su (1987), Ichikawa's first feature film, to Masahiro Motoki's struggling manga artist in Tokiwa: The Manga Apartment (Tokiwa-so no Seishun, 1996) and the curiously old-fashioned brother and sister in Tokyo Siblings (Tokyo Kyodai, 1995), fit the jimi label well enough, whatever their outer quirks or inner fires.

Jimi is also one word that pops into my head when I return from abroad, especially from the anything-but-quiet United States, and see the drably, if neatly, dressed commuters silently absorbed in their i-Pods or comics or thoughts on the train from Narita. These are people who never appear in the street fashion magazines, but, with a change of costume and hairstyle, would not have looked out of place in the Japan of Hearn - or Yasujiro Ozu.

Also jimi are the corners of Tokyo where so many of Ichikawa's films unfold, such as his native Kagurazaka, which still evokes the atmosphere of the hardscrabble post-war period, when Ichikawa was a boy, as well as the glory days of the geisha who once flourished there.

But while liking such jimi people and places, Ichikawa was anything but a nostalgist. Like his cinematic heroes, including François Truffaut, Eric Rohmer, Ken Loach and Mike Leigh, as well as the inevitable Ozu, he was interested in revealing human truths behind seemingly ordinary and everyday surfaces, minus the sentimentality and melodrama endemic to Japanese "humanistic" films.

He could be quite unsparing to his heroes, from the humiliating disaster that befalls Tomita's defiant outsider in front of her entire high school at the end of Bu*Su to the madness that destroys Hiroyuki Sanada's desperate writer in Tadon and Chikuwa (Tadon to Chikuwa, 1998), but he never treated them as disposable directorial puppets. They had a solidity and dignity as individuals, whatever their eventual fates.

No wonder actors wanted to work with him, even though he could be tough on them. (He told me that Tomita, then a teen idol TV star and singer, "became neurotic" on the set of Bu*Su."I was too hard on her," he said wistfully.) He elicited performances that, quite different from the star's usual perky or macho image, were often career peaks. Looking at Rena Tanaka, another pretty teen idol, he saw a loneliness he brought out to stark and memorable effect in Tokyo Marigold, in which Tanaka plays a friendless girl who volunteers to be a "substitute lover" for a guy she likes, while his real girlfriend is abroad.

Also, as much as Ichikawa enjoyed looking back at an earlier Japan, even making Tokyo Siblings as an Ozu tribute, he was also in tune with his times. No Life King (1989) is a prescient early look at children so absorbed in the virtual reality of a computer game that it begins to invade their non-digital world, with disturbing consequences. Ichikawa's treatment is anything but sensationalistic; instead the film reflects the real-life ways in which "urban legend" memes pass from mind to young mind like viruses.

But the jimi label, though only partly justified, stuck, to Ichikawa's discomfort - and disadvantage. In the 1990s, more raucous voices among his generation of Japanese directors, from Shinya Tsukamoto to Takashi Miike, grabbed the attention of foreign fans and became cult favorites.

At the same time, he did not, like Takeshi Kitano, Naomi Kawase or Hirokazu Koreeda, make films that advertised their seriousness to prestigious festivals with austere stylistics, tamped-down emotions or, in the case of Kitano, extreme violence. A much-in-demand director of TV commercials before and after he started making features, Ichikwa had a gift for revealing poignant moments of transient beauty in everyday settings - the classic Japanese aesthetic of mono no aware (often translated as the "pathos of things"). He could even make a morning sky over a typical Tokyo cityscape look glorious - less with camera or editing tricks than his superbly perceptive eye.

This gift, though, did not make him - to use that 1990s buzzword - edgy. He got his share of invitations and prizes from foreign festivals - Montreal gave him its Best Director award in 1997 for his relationship drama Tokyo Lullaby (Tokyo Yakyoku), but the highest honors, as well as the critical trends, flowed elsewhere.

This struck me as a gross oversight and I beat the drum loud and hard for Ichikawa's films in The Japan Times, to little avail. In 2004 I presented four of Ichikawa's films - Bu*Su, Tadon and Chikuwa, Dying at a Hospital (Byoin de Shinu to iu koto, 1993) and Tokyo Marigold (2001) at the Udine Far East Film Festival, with Ichikawa present - the first such festival tribute in the West.

Dying at a Hospital, Ichikawa's masterpiece, has been little screened abroad - partly, I suppose, because of its off-putting, if entirely accurate, title. Seeing it on the big screen in Udine's Teatro, I was struck by not only his stories of five terminal cancer patients, told with sensitivity and restraint (all based on a book by a practicing physician), but the interspersed montages of ordinary people doing ordinary things - hunting for clams at the seaside, watching a baseball game, dancing at a Bon festival. Ichikawa filmed them in his spare moments over a period of months, then edited down hundreds of hours of footage.

These montages express the preciousness of life, the presence of the eternal in the everyday with grace and clarity. Much of their power derives from their juxtaposition with the scenes of cancer patients who will never experience those ordinary things again. "Death is the great equalizer - it's something that comes to everyone, " Ichikawa told me. "...I thought a movie about death shouldn't have one hero. Everyone should be the hero." In other words, the joyously living as well as the painfully dying.

Having had my own brush with mortality just prior to Udine - I was rushed to a Frankfurt hospital coughing blood after coming down with severe bronchitis - I saw that film, sitting next to Ichikawa, with fresh eyes. There is not a single tear-jerking scene in it, but I found myself sobbing uncontrollably - and trying mightily to restrain myself, so I wouldn't look like a total fool to Ichikawa. After the screening, and accepting congratulations from fans whose faces were as tear-streaked as mine, Ichikawa and I walked out of the theater. "I just make films that make people cry," he said with a sigh not entirely ironic.

By this time he had finished the film that he is now best known for - Tony Takitani (2004).

Starting with Tadon and Chikuwa, Ichikawa had made film after film in which he tried to break with his jimi image, including the cartoony, if beautifully shot, Ryoma's Wife, Her Husband and Her Lover, with playwright/director Koki Mitani writing the script ("It was a failure...Mitani probably should have directed it himself," he told me.) Tony Takitani, however, was by far the most successful.

Based on a story by Haruki Murakami about an introverted illustrator (Issei Ogata) with a fashion-crazed wife (Rie Miyazawa), Tony Takitani may have had certain affinities with Ichikawa's earlier films, from the withdrawn personality of the hero to the restraint of the shotmaking, but it was in fact another experiment, with a laterally moving camera shifting from scene to scene, like sliding picture cards in a kamishibai (traditional picture play), as a dulcet-voiced narrator told the story. It won the Special Jury Prize, Youth Jury Prize and FIPRESCI Prize at the Locarno fest, as well as many honors elsewhere, but I found it overly stagey and literary (though Murakami himself apparently loved it.)

When Ichikawa died, age 59, of a cerebral hemorrhage on September 19, he was finishing post production on his last film, "buy a suit." The winner of the Best Picture Award in the Japanese Eyes section of the recently ended Tokyo International Film Festival, this 47-minute film is a return to Ichikawa's indie roots, shot entirely with an HD cam.

The story is simple - a young woman (Yukiko Sunahara) arrives in Tokyo from the countryside to look for her long-lost older brother (Sabakichi) - a brilliant but eccentric man who recently sent her a postcard ending with a vague reference to his current residence.

After meeting with her brother's former classmate and close friend, who lost track of him years ago, she tracks him down - and finds him living under a blue tarp near a bridge. He tells her he is planning to get back on his feet with a dubious-sounding business venture, but she is sceptical. An enterprising sort, she arranges a meeting with his one-time lover - a blowzy bar proprietress - hoping for a reconciliation and a return to a more-or-less normal life for her brother.

Ichikawa films this journey into the past - and a possible future - with no sets, no professional actors, nothing but his gift for transforming the mundane and temporal into the transcendent.

There is a certain rhythm to the shots in "buy a suit." Scenes of traffic or pedestrians transition to long or medium shots of the principals, finally moving in for close-ups. There is, however, nothing predictable or obvious. Instead, Ichikawa leads us steadily, delicately into his characters' hearts - and the mysteries of life. He makes Tokyo look idyllic, despite its urban clutter and noise, but he also exposes its cruelties and insanities. The ending is a devastating, haunting reminder of our human fragility.

"buy a suit" is a brilliant, fitting coda to a life and career cut too short. And, yes, it is the most jimi Ichikawa film of all - small, quiet, real.