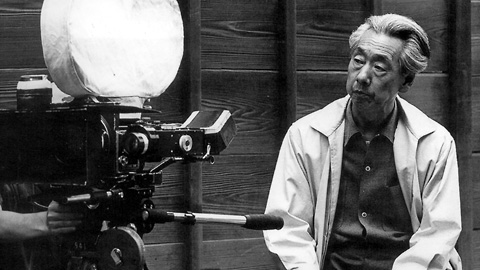

Mikio Naruse – A Modern Classic

- published

- 11 February 2007

Although Mikio Naruse is counted amongst the great Japanese classical masters of cinema, alongside Kurosawa, Mizoguchi and Ozu, his reputation has only recently reached the West. This is largely due to the lack of availability of his films, a situation lately improving. He did not win any international film festival prizes during his lifetime. Also, critical evaluation of his films within academic circles has never been strong. It is actually curious that Japanese cinema is always taught by centering on the three names mentioned above, and throwing in Oshima to highlight the new wave and Kitano as an example of the current cinema. So a re-evaluation of Naruse as one of the masters of Japanese cinema is a necessary rethinking of the canon.

The invisibility of Naruse might also be due to his style. He was not as elaborate as Kurosawa, and neither did he develop a highly distinctive personal bookmark style, as did Mizoguchi with his long takes or Ozu with his parametric treatment of space. Naruse's style is calmer, simpler and "easier", but it hides underneath it a richly depicted view of human relations, especially those within or resembling domestic situations. The National Film Center in Tokyo already screened several Naruse seasons this decade, and, following the interest, Japanese bookshops now stock a number of new books on the director. In the West, Naruse retrospectives started with the 1983 Locarno Film Festival. It took until very recently for critics, researchers and historians to follow suit, notable among them Jean Narboni, Ben Singer, Freda Freiberg, Catherine Russell, Audie Bock, Alain Masson, Chris Fujiwara and Alexander Jacoby.

Of interest are the recent screenings of pre-war films, such as The Whole Family Works (Hataraku Ikka ,1939), which reveal a tendency towards realism and narrative experimentation. They certainly widen the image of Naruse as a stylistically "invisible" director, as he experimented both with visual style and with the flashback structure of his films. In his first sound film, Three Sisters with Maiden Hearts (Otome-Gokoro Sannin Kyodai, 1935) Naruse had the chance to experiment with voice-over narration. Thus, alongside our image of Naruse as a mature master of 1950s and 60s, there is another, exciting Naruse to be found in the prewar period. Naruse's prewar films reveal a tendency towards flashier camera work, including tracking shots and cutting over the 180 degree line, as opposed to his more "invisible" postwar style. This more apparent style can be noticed in Morning's a Tree-lined Street (Ashita no Namiki Michi, 1936), a story about two young women who work in a Ginza coffee shop and struggle with their lives and relationships. Indeed, the characters and themes dear to Naruse are there: bar hostesses and coffee shop waitresses who try to support their families, impossible love, and the role of money in relationships.

As the early films already reveal, Naruse worked within the domestic and female-oriented genres, such as shomingeki and domestic melodrama. Already the titles of his films - Mother (Okaasan), Husband and Wife (Fufu) and Older Brother, Younger Sister (Ani Imoto), give an indication about Naruse's interests. Naruse's film center on dialogue scenes, within which a web of human relationships and emotions simmer just under the peaceful surface. The setting of his stories was therefore close to Ozu's, but while Ozu pictures his characters getting on peacefully with their lives despite some disappointment, Naruse's characters seem to deal more actively with their disappointments, and finally end up being more bitter about them. In this sense Naruse's pessimistic view on relationship problems strikes a very modern sensibility, one that we still can identify with. Naruse has been compared to Anton Chekhov on his treatment of human life. If one goes to look for biographical sources, those can be found too: perhaps the numerous women supporting themselves and their children without a husband are a reflection upon Naruse's own childhood of having been raised by his sisters after his parents' deaths. The protagonist of Mother (1952), who gives up her child for adoption is a typical female character in Naruse's films, as well as the war widow who runs a small shop in Yearning (Midareru).

Lacking the funds, Naruse never received a university education, and instead took a job as a set construction assistant at the Shochiku studios. After ten years of assistantships - a normal term before achieving the position of director during the heyday of studio system - Naruse was allowed to direct slapstick comedies.

Although bitter dramas centering around women and families are Naruse's trademark, one schould not forget his sense of humor. Naruse had a knack for bringing out his characters' humorous sides, for example in the sisters and brothers fathered by different men in Lightning (Inazuma, 1952).

Naruse also wove the practical topic of money into the relationships he was depicting. For example, in Late Chrysanthemum (Bangiku, 1954) the female moneylender goes around trying to collect debts back from the geishas, but falls prey to a greedy man herself. The same theme with money as the basis of relationships continues in Flowing (Nagareru, 1956). Family members are married off for fortune and survival rather than the sake of tradition, for example in Summer Clouds (Iwashigumo, 1958) depicts the changing of family relations as being always tied to economic turns.

Naruse directed for two studios. It has been claimed that Shochiku thought one Ozu was enough, and that this is why Naruse switched to PCL, which was later to merge into Toho. It is under Toho's roof that he directed his most famous films, but he also branched out to Shintoho and Daiei. Naruse's first Toho film was Three Sisters with Maiden Hearts, based on a Yasunari Kawabata novel. Naruse was to return to Kawabata in 1954 with Sound of the Mountain (Yama no Oto, 1954). Naruse loved literature from his youth on, and was to film numerous novels, many of them from Fumiko Hayashi, Naruse's favorite writer. These include Repast (Meshi, 1951), Lightning, Late Chrysanthemum, the partly autobiographical Lonely Lane (Horoki) and Floating Clouds (Ukigumo, 1955).

The story of Floating Clouds about a woman's struggle in postwar Japan also offers magnificent acting from one of Naruse's regulars, Hideko Takamine, the quintessential Naruse actress with her ability to reflect women's hopes, disappointments, earthly practicality and bitterness. The same bitter fight between one's own hopes and the limits of the surrounding reality are brought out wonderfully in Takamine's role as the bar owner, mama-san, in When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Onna ga Kaidan o Agaru Toki, 1960). Another Naruse regular was Haruko Sugimura, who specialized in tougher, middle-aged women's roles, for example as the money lender in Late Chrysanthemum. Setsuko Hara also played a good number of roles in Naruse's films.

The stage is often a cramped apartment or a restaurant, bar or guest house frequented by average folk. Naruse used to block his actors on such narrow stages that they were hardly able to move. In dialogue scenes Naruse filmed one actor at a time from the beginning of the scene until the end, before he turned his camera to the co-actor. Acting in Naruse films was not always an easy task: many of his regular players complained that the director never gave them particular instructions on what he wanted from a scene [ 1 ].

In outdoor scenes the bridge is also a crucial set for dialogue scenes, underlining the characters' aim towards something. Naruse's style became more and more simple over time and he did not seem to have any need to highlight his message with visual means. In his last films the camera hardly moves at all. This simplicity, however, was created through a refined system of filming: Masao Tamai, Naruse's regular cameraman, has told how Naruse wanted the outdoor scenes to be filmed so that one actor moves and looks over his/her shoulder at another actor, who then moves. The takes were done with a non-moving camera, but this filming style created a flow in the scenes. Akira Kurosawa, who briefly worked as an assistant to Naruse in the 1930s, has analyzed that Naruse's way to pile short takes on top of each other gives an impression of one long take [ 2 ].

Although as a director he is central to the Classic period, there is something very modern about Naruse's characters and stories. This is perhaps one of the reasons for the recent interest in his films. Watching a Naruse film is not about examining "how they used to make films". It is about getting involved in stories that still strike a chord with us.