Pioneers of Japanese Animation at PIFan – Part 1

- published

- 23 September 2004

Thumbing through the pages of the Asiana in-flight magazine on the plane from Tokyo to Korea for the 8th Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival (or PIFan for short), I stumbled across an amusing article about this year's Cannes, which ended with the writer asserting, "On a personal note, I believe that it is the insidious hegemonic hold of colonialism that propels Korean directors or producers to desire the red carpet of international film festivals. I also believe that film festivals are where various political and cultural powers work and clash to determine norms and standards."

Pretty opinionated stuff considering the soporific material that usually passes as reading fodder for jaded air travellers. But if I may be bold enough to add my own rebuttal, it would have to be strongly in the defence of the film festival as one of the few milieus that afford the general public the opportunity to realise fully the joys and diversity of this magical art form. Because like travel itself, cinema has the potential to transport us to a myriad of fantastic worlds. It also has the ability to open windows on different mindsets, cultures, time periods and ways of life that we might otherwise never get a chance to experience.

Whatever the motivating factors are that continue to coax directors of various nationalities onto the red carpet, the appearance of the likes of Kim Ki-duk (The Isle, Samaritan Girl), Lee Chang-dong (Peppermint Candy, Oasis), Park Chan-wook (Joint Security Area, Old Boy) and a whole host of other equally challenging and inspiring Korean directors on the world stage in recent years is a development to be celebrated, not griped about.

The truth is that international film festivals are far less elitist, snobby or highbrow affairs than most people assume, and each has an individual flavour of its own. Witness PIFan for example, held this year between July 15 and 24. Along with Jeonju and Pusan, it is one of Korea's top three festivals, and the one most tailored toward fans with a taste for the fantastic and the bizarre. It's hard to think what sort of "norms and standards" are being determined by a festival that mixes a tribute to German arthouse splattermeister Jorg Buttgereit and a focus both on the movies of Troma and the Shaw Brothers with a series of screenings of experimental and avant-garde works from the 1940s and 50s by the likes of Stan Brakhage and Maya Deren, programmed around British director Paul Cronin's documentary Film as Subversive Art: Amos Vogel and Cinema 16, about the maverick programmer and founder of the seminal New York film club.

PIFan has to have one of the most "anything goes" approaches to programming of any festival I can think of. This could be taken as criticism, but the end result is a refreshingly broad and exciting selection of movies for its visitors. Out of the 261 films screened from 32 countries under the theme of Love, Fantasy And Adventure, there was truly something for everyone. Personal highpoints included Gagamboy, the Philippino spin on Spiderman; Proteus, a boldly experimental South American/Canadian look at a taboo interracial homosexual relationship in 18th-century South Africa; two immensely enjoyable Norwegian movies that caught me completely off-guard, the perky teen-drama Just Bea (Bare Bea) and the small-time hick black comedy Jonny Vang (which I thought played a little like a Nordic version of Nobuhiro Yamashita's No One's Ark); and the epic prison reform drama Virumaandi from India, shot in the Tamil language and starring, written, and directed by Kamal Haasan. The rousing 30-minute prison break at the film's coda, which featured possibly more skewered torsos and severed limbs than the entire George Romero filmography, had local audiences leaping in their seats, hollering and punching the air with delight.

As far as Korean movies went, a rare treat was dug up from the national archives in the form of a restored version of Yu Hyun-mok's long-forgotten An Empty Dream (Chunmong), screened for the first time in almost 40 years since its release in 1965 when it was immediately banned due to a fleeting few frames of nudity (now snipped from the print) from its lead actress. Surreal, experimental and hypnotic, the story of a young lady hallucinating under the dentist's gas and being chased around a series of baroque landscapes caused gasps of recognition from those savvy with the obscurer corners of Japanese cult film history when it became clear that the source material was none other than Takechi Tetsuji's Daydream (Hakujitsumu, 1964). An Empty Dream's director claimed that he had never seen the original, but that it was common practice for the Korean industry to use scripts of Japanese films. With its opulent set designs resembling those of that masterpiece of German Expressionism The Cabinet of Caligari (1919), Yu Hyun-mok's take on the same script is infinitely more stylish and cinematic than the rather cheap-looking original.

Recent Japanese film was well represent by, amongst others, Isao Yukisada's whimsical teen drama A Day on the Planet, Makoto Shinozaki's charming canine caper Walking with the Dog, Katsuhito Ishii's The Taste of Tea and one of the best Japanese movies of the past year, Isshin Inudo's beguiling Josee, the Tiger, and the Fish.

But arguably the most eye-opening of the Japanese works screened at this year's PIFan were all over 60 years old. In a year which is surely going to be remembered as a high-water mark for Japanese animation, PIFan decided to celebrate this most popular aspect of Japanese pop culture not only with screenings of Mamoru Oshii's recent cyberpunk stunner Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence, but also a bold selection of seven programs screened under the title Pioneers of Japanese Animation: From Tekobo to Momotaro. I say bold, because most of the films screened were made during the time when Korea was under Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945). Given that Korea only lifted a long-term ban on Japanese cultural imports in 1998, the Korean reaction to these works was surprisingly appreciative.

I think it's fair to say that allusions to Japanese anime immediately have most people thinking of cutesy pink-haired, sailor-suited heroines with dewy, wide eyes and short skirts, or perhaps, on the other side of the coin, apocalyptic visions of societies with man and machine locked in an uneasy symbiosis. That anime is such a misrepresented genre outside of Japan is no doubt due to the fact that even within the country the chances of tracing a lineage back to its origins have been hampered by the tragic unavailability of prints for viewing. War, earthquakes and the ravages of time have all, as with much of Japanese cinema, taken their toll, and much of what remained has been in the form of scratchy 16mm prints owned by private collectors, most of them wanting a good deal of money before they part with such rare treasures.

Fortunately, due to the selfless detective work of Yoshio Yasui of Planet Bibliotheque de Cinema in Osaka, a large number of pivotal early works have been salvaged, restored, blown up from 16mm to 35mm and placed in the National Film Centre archive. Some of the 53 works screened at PIFan have already been screened as part of "The Other Anime" series run by the University of Michigan in the fall of 2003, at Frankfurt's Nippon Connection festival in April 2004 and as part of an exhaustive programme at the National Film Centre in Tokyo in July and August 2004. Unfortunately, the condition of these prints, especially with the noticeable flaws in their contrast and their soundtracks (in fact, made in the silent era, many of them don't have soundtracks at all) has meant that releasing them as DVD packages may prove a commercially tricky undertaking, more of interest to specialists and film historians than to the general public. It is precisely this kind of problem that has resulted in the invisibility of a lot of nations' early film histories, meaning that for the moment at least, the best chances to see works such as these are via the precious rare windows of opportunity opened up by festivals such as PIFan. The festival also staged a fascinating panel discussion event with Planet curator Yasui and animation expert Yasushi Watanabe, author of the crucial 1977 History of Japanese Animation, which provided a welcome wealth of background context to the films screened there.

The history of the animated cartoon begins in America, kicked off by a character known as J. Stuart Blackton (1875-1941). Born in Britain, Blackton first arrived in the US at the age of 10 when his family moved there from Sheffield. After a chance meeting with Thomas Edison, he founded the American Vitagraph Studio with fellow British émigré Albert E. Smith, making comic shorts which the pair utilised as part of their vaudeville stage acts. In this way, Blackton made the 3-minute long Humorous Phases of a Funny Face in 1906. Another early landmark came later with Windsor McCay's Gertie the Trained Dinosaur (1914), which consisted of a total of 10,000 images all drawn single-handedly by its creator. The animated short film soon caught on throughout the West, and it was such films from the US, Britain and France that were the first examples of this new offshoot of early cinema to be introduced into Japan around 1914. In 1915, 21 foreign animations played in Japan, and inspired by their success, the first works of Japanese animation soon followed.

There is some confusion as to who can claim the distinction of being the first Japanese to start work in the field, but three figures are cited as producing works at around the same time: Oten Shimokawa (1892-1973), Junichi Kouchi (1886-1970) and Seitaro Kitayama (1888-1945). The first two came from a cartoonist background, both working for the satirical magazine Tokyo Puck, and were commissioned by the companies Tenkatsu and Kobayashi Shokai respectively to produce their first works. Kitayama, however, was a watercolour artist with an interest in developments in Western art, and it was he who approached Nikkatsu to undertake the company's first work in the field in 1917.

Of the three directors, Shimokawa was the first to have his work released into theatres, with Imokawa Mukuzo, The Janitor (Imokawa Mukuzo, Genkanban no Maki) reported to have come out in January - although there is some speculation as to whether this film ever existed beyond a title, because as is the case with all of the five works Shimokawa produced before leaving the field in the very same year, not a trace remains.

After its invention in 1915, cel animation rapidly became established as the standard technique for studio animation in the West. It utilizes the labour-saving process of using several layers of transparent plastic overlaid over one another, as opposed to drawing each frame individually, so that parts of the frame can be repeated. During these early days, the celluloid used for cel animation (acetate is now used) was in scarce supply in Japan, so Shimokawa pioneered two timesaving techniques of his own in his work. One was to draw each individual frame in chalk on a blackboard, rubbing out the images and redrawing from frame to frame. Another technique was to make thousands of copies of each individual background, and cover a part of each with white paint in order to draw the moving foreground characters over it.

With his first film, Hanawa Hekonai, Famous Swords (Hanawa Hekonai, Meito no Maki) released in June of 1917, Kouchi was the last of the three to have his film released. Of his oeuvre, only Hyoroku's Warrior Training (Hyoroku no Musha Shugyo, release date unknown, but between 1917-1925) remains. Contemporary reviews however were quick to point out a marked superiority in technique with that of the first works of his two contemporaries, often utilising the cut-out technique in which each frame is composed of individual cut-out parts of, for example, paper, and manipulated from frame to frame. Cut-out animation, often in combination with other methods, became one of the most popular approaches used by later animators such as Sanae Yamamoto, Yasuji Murata, Hakuzan Kimura and most notably, Noboro Ofuji (1900-1961), up until the point where cel animation became a more affordable option. Kouchi left the industry in 1930, after producing his final work Chopped Snake (Chongire Hebi), leaving little in the way of written records of his animation methods.

It is Kitayama, the third of these figures, who is in many ways the most significant. His first animation, Monkey Crab Battle (a.k.a. The Crab Gets Its Revenge on the Monkey, or Saru Kani Gassen) was released in May 1917. Records show that Kitayama was the most prolific of the three (around 30 titles can be attributed to him), bringing out ten in the first year alone, though only his Taro the Guard, The Submarine (Taro no Banpei, Senkotei no Maki, 1918) survives. More significant, perhaps, was the diversity of his output: advertising films, animated sequences for live action films, political propaganda and later educational films intended for the classroom, such as his last work Circle (En, 1932). His chosen animation technique, again, was drawing his moving figures over detailed paper backgrounds, though he later moved to paper cut-out animation. But his most important legacy was in establishing Kitayama Eiga Seisaku-sho, Japan's first animation studio, in 1921.

Whilst nothing from these three initial pioneers survives in a state fit for public screening, one can perhaps get an impression of what their works were like from those that immediately followed in the early 1920s. The earliest to play at PIFan was the The Hare and the Tortoise (Kyoiku Otogi Manga: Usagi to Kame, 1924), a straightforward rendition of Aesop's famous fable directed by Sanae Yamamoto (1898-1981). Typical for most animation of the time, at under 7 minutes in length it is very short, and the print does not contain a soundtrack. It would have been originally screened with a benshi narration and a musical accompaniment, shown not only as parts of programs in conventional cinemas, but also in public places such as schools, a venue which would assume an increasing importance during the next decade when Japanese animation would take on an important role as propaganda for youngsters.

Sanae Yamamoto was a crucial figure in Japanese animation history. Learning the ropes at Seitaro Kitayama's studio, he later became one of the founders of Toei Doga, contributing significantly to such seminal early features as Legend of the White Serpent (1958), Journey to the West (1960) and Arabian Night: Sindbad's Adventure (1962). As such, he bridges the gap from animation's inception in Japan to the crucial period when it effectively came of age in the late 1950s, with the industry simultaneously starting to produce feature-length colour works that attempted to rival higher-budgeted American competition, and with manga artist Osamu Tezuka's efforts to produce work cheaply and en masse for television. He thus provides us with a convenient entry point through which to examine the style and content of this early animation period.

Typically, the earliest Japanese animated works were based on tried-and-tested folk stories, either international favourites or ones of a more specifically local flavour passed down from generation to generation, and more often than not with a strong moral content. Aesop's aforementioned tale of the race between the brash, flash but ultimately overly-complacent hare and his slow but steady rival is a fine example.

From its opening image of the tortoise scrambling from the river onto the bank on which the hare is sleeping, butterflies fluttering in the foreground, the first thing that registers is the quality of detail in the monochrome pencil line drawings that make up the work. With every scene staged as a single tableau in which the movement of the main characters occurs, the animation is understandably jerky and crude, though never distractingly so. Rather than the more rounded, simplified figures that soon became associated with cartoons, in Yamamoto's work the drawings of the animals and backdrops are incredibly realistic, even if, as in the case of the tortoise's victory dance on the hilltop, their actions aren't.

This fixation with detail at the expense of fluidity is rather typical of the time. A similarly elaborate style was manifested in the work of Yasuji Murata (1896-1966), who started his career at the Yokohama Cinema Company creating intertitles for both educational films and the short animations of the American Bray Studios, before being drawn more wholeheartedly into the world of animation. Murata studied the animation techniques of Yamamoto, accounting for the evident surface similarities in their works, and his first work was Monkey Crab Battle in 1927, a remake of Kitayama's seminal debut of the same title.

Despite its comic subject matter and narrative, Animal Olympics (Dobutsu Orimpikku Taikai, 1928), based on an original story by Murata, also opted for an incredible fidelity in its depictions of the various animals that gather to compete in this cartoon inspired by the 9th Olympic Games held in Amsterdam the very same year it was made. The elephants, rabbits, pigs and hippos that all take part in the various events, overseen by a lion and a tiger, are all drawn in outline with a considerable regard for the shape and dimensions of the real creatures, and most remain on all fours throughout the games - when they are not hurtling through midair or being squashed beneath their larger competitors, that is! The subject matter allows for a considerably degree of humour within the 6-minute running time, which is comprised of a series of comic incidents such as the polar bear's pole volt and a pig cheating at the hurdles by swallowing a balloon allowing him to float high above the obstacles until he is punctured by a javelin thrown by an elephant.

A similar degree of verisimilitude in the depiction of the characters is on display in Taro's Steamtrain (Taro no Kisha, 1929) in which the young human hero becomes the conductor of a train whose passengers are all portrayed with human bodies and animal heads. The film advocates good manners and consideration to fellow travellers as Taro patrols the carriages making sure the passengers are all adhering to the basic codes of common courtesy. As a goat tries to squeeze into a seat occupied by three little piglets while their portly father reads the newspaper occupying an entire row opposite, Taro arrives to remove papa pig's bag from the seat. Meanwhile, two large hippo ladies with kimonos and elegant coiffures throw banana skins on the floor, whilst a bull and a horse sit facing each other quaffing sake and getting progressively rowdier before the bull lapses into a drunken slumber, drool dripping from his bovine mouth.

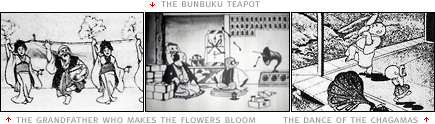

For much of the time Murata stuck with characters already established through comic strips, picture books or folktales. An example of the latter is the 5-minute-long The Grandfather Who Makes The Flowers Bloom (Hanasakajijii, 1928), based on a tale of an old man who spreads ashes on the roots of a dying cherry tree, causing it to bloom and buried treasure to appear beneath its roots. He is spied upon by an avaricious neighbour, who reports what has happened to his landlord. In search of easy gains, the landlord tries doing the same thing. However, the ashes blow into his face making him look a fool in front of everyone.

Fine, intricate line drawings and folklore-based subject matter are also in evidence for Removing the Lump (Kobutori, 1929), based on the tale Kobutori-jiisan about an honest old man who dances with the tengu, mythical bird-like creatures, in order to have them remove an unsightly lump from the side of his face. When his ungracious neighbour tries the same thing in order to get a similar lump removed from his cheek, he ends up with yet another one placed over the original. This film makes fine comic usage out of the grotesque but intricately sketched facial expressions of the old men, though again, this level of detail comes at the expense of the smoothness of the animation.

The tengu are but one of the mythical creature who crop up frequently in these early films. A more enduringly popular attraction was the tanuki, or raccoon dog. Real-life creatures indigenous to Japan, folklore has imbued them with a near mythical status as rotund fun-loving creatures with black bandit-masks and, like their rivals the foxes, an innate magical ability to shape-shift into different objects and creatures. These guardians of the natural environment crop up time and time again in children's stories and animation, the most memorable recent appearance being in Studio Ghibli's Pompoko. There were even a string of live action musical comedies in the 1950s celebrating the lives of such bawdy bands of brothers, a genre later revived by Seijun Suzuki with Princess Raccoon (Operetta Tanuki Goten, 2005).

The tanuki cropped up in Murata's The Bunbuku Teapot (Bunbuku Chagama, 1928), in which a young loafer rescues a tanuki that has been caught in a trap. As a sign of gratitude, the tanuki transforms itself into a teapot, which the man donates to a Buddhist temple. Here the creature reverts back to its original form and causes havoc.

In the similarly themed The Dance of the Chagamas (Chagama Ondo, 1934), the mischievous creatures are lured into a Buddhist temple by the sound of the shaven-headed monk and his young acolyte playing gramophone records, which they attempt to steal. Due to the efforts of its director, Kenzo Masaoka, this film represents one of the most significant industrial turning points in Japanese animation, in that it was the first work to be completely cel-animated. Whilst there's no real loss of detail compared with the works that came before it, the movements are considerably softer and more fluid.

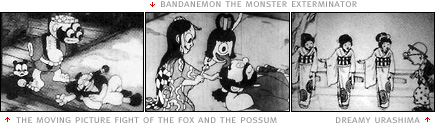

Tanukis were also behind the ghostly goings-on in Ikuo Oishi's 11-minute The Moving Picture Fight of the Fox and the Possum (Ugoki-e Kori no Tatehiki, 1931), in which a fox disguised as a samurai spends the night in a deserted temple inhabited by what at first appears to be a monk and his acolytes. The monks turn out to be a tanuki family, who transform into a variety of grotesque creatures (similar to the yokai, or goblins, later popularised in Shigeru Mizuki's manga series, Gegege no Kitaro) to drive out this unwelcome visitor. Oishi's film is worth noting in that it takes a conscious break away from the detailed representational style of the early works of Murata and Yamamoto into more caricatural, simplified, and rounded character designs apparently influenced by American animations such as Felix the Cat. This allows the animator to invoke more accurate emotional content through the use of such devices as rolling eyes and twitching eyebrows to portray the characters' fear, as well as bringing a greater degree of fluidity to the movement. In a similar vein, Yoshitaro Kataoka's Bandanemon the Monster Exterminator (Bakemonotaiji no Maki, 1935) sees the trainee warrior of the title lured by a village notice board to clear out the spooks from a nearby haunted castle. The creatures in question of course turn out to be tanukis, who disguise themselves as beautiful women to divert the young warrior's attention from the task at hand.

Another recurrent folk tale that has found its central premise reworked through animation again and again is the myth of Urashima Taro, a fisherman transported from the seashore into a fantastic underwater world on the back of a giant turtle. One of the first examples of the tale is Hakuzan Kimura's Dreamy Urashima (Nonki na Tousan Ryugu Mairi, 1925), in which a lazy man wakes up from his sleep and heads off to the seaside to spend the day fishing. There is a brief live-action shot of the sea swelling before the film returns to its animated fantasy world when a beautiful girl appears on the beach and lures him into the waves, transforming into the legendary turtle and carrying him beneath the surface to an undersea kingdom of fish and squid. Here he is welcomed by a bevy of kimono-wearing lovelies who lead him to a stately court full of musicians and dancers. As a ballerina pirouettes on the palace floor in front of him, he is plied with alcohol and handed a small gift box, before being escorted to a giant scallop shell that rises through the water taking him back to the surface. When he returns home, he finds he has aged so much that his wife and son no longer recognise him. He opens the gift box and a hideous demon springs from it and squashes him beneath its fists, at which point the man wakes up, and realising that the events of this story have all been a terrible nightmare, hurries out to work, alerted to the potential dangers of a life spent in idle daydreaming.

In this film, Kimura's flat, 2-dimensional style is very similar to the newspaper comic strips from which a lot of early animation drew its characters and stories. The stooping, bowler-hatted kimono-wearing, central character is virtually identical to the one at the centre of his earlier film Easy-Going Guy Yamazaki Kaido (1925), which was based on a newspaper cartoon drawn by Yutaka Aso published in the Hochi Shinbun. A similar design was in evidence in Kimura's folk-based morality tale, The Story of Shiobara Tasuke (Shiobara Tasuke, 1925) in which a farmer, accompanied by his faithful horse, works his way up in life to become a wealthy shopkeeper. A former painter of cinema signboards, Kimura later vanished as a significant influence on the field when he was arrested by the police for producing Japan's first pornographic animation. Aside from this dubious claim to fame, his work can be considered of fairly secondary importance to his contemporaries.

One of the most interesting presentational aspects to Kimura's Dreamy Urashima is in the depiction of the denizens of the undersea kingdom, like the fantastic characters from Murata's films, with realistic human bodies and fish's bodies at their heads. Remarkably similar-looking fish-man hybrids featured in the opening scenes of Murata's The Octopus' Skeleton (Tako no Hone, 1927), which details the story of how the octopus lost its backbone in a squabble with a monkey. Again, it cross-references the Urashima Taro story as the two find themselves driven out into the middle of the ocean on the back of a giant turtle before they clash with a huge whale.

If a lot of the early animations from the 1920s now seem difficult to watch when presented at festivals such as Puchon, it is in no small measure because of foreign audiences' unfamiliarity with the folk stories and characters that feature within them. And again, it must be remembered that when the films were originally screened, they would have been accompanied by the ongoing accompaniment of the benshi explaining the events unfolding on the screen. A number of the films featured Japanese explanatory intertitles, which are of course no use for non-Japanese speakers, but one interesting thing to note, and one that holds for most Japanese silent film, is that the diegesis of the narrative in these early works is often only partially contained within the film itself. In other words, in the absence of any other contextual information, it is not always possible to follow the story through the images alone.

Throughout the 1930s, synchronised sound would come to replace the benshi, and many older films were reissued in new prints with new pre-recorded soundtracks. Kenzo Masaoka, who introduced groundbreaking changes into animation technical practice with a completely switch to cel animation in The Dance of the Chagamas in 1934, can also be credited with another "first"; the first fully-synched animated "talkie" in 1932, entitled The World of Power and Women (Chikara to Onna no Yo no naka), though it appears that there are no prints of this film in existence any more. Similarly, as advances in animation technique increased the expressive abilities of the image track, the films of the 1930s begin to work far more successfully as stand alone works then their predecessors. A new era of animation had begun…

(Go to Part 2).