The Realism of Fantasy: A Tribute to Fujio Morita

- published

- 15 December 2014

The late Fujio Morita (1927 – 2014) was among Japan’s cinema’s greatest cinematographers, alongside Kazuo Miyagawa (Ugetsu) and for instance Chikashi Makiura (Lone Wolf and Cub). He straddled the Golden Age of the major film studios and the independent era following the collapse of Daiei in 1971, lensing films for such directors as Kenji Misumi, Kazuo Mori, Hideo Gosha (with whom he made 13 films, including Hitokiri), and actor-producer-director Shintaro Katsu.

Zatoichi: A Lover's Suicide Song

I had the honour of meeting Fujio Morita twice, in Kyoto in 2004 and 2006, for interviews about Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon as well as the Lone Wolf and Cub saga, and his collaborations with both Shintaro Katsu and Hideo Gosha. Though he was already 79 years old in 2006 and a great veteran, he was a no-frills man who cycled his way to the interviews and back...

Born in 1927 in Kyoto, close to the Daiei studios, Fujio Morita loved the mechanics of photography. He studied industrial architecture and chemistry, and learned a lot from a certain Mr Miyata, who was instrumental in the development of both Toyo Laboratories and Imagica. By chance Fujio Morita was called upon to give private tuition to the child of Daiei Kyoto’s CEO Masaichi Nagata. Morita subsequently entered Daiei in 1947, where he started out as an apprentice cameraman with Kohei Sugiyama (Gate of Hell / Jigokumon) and Soichi Aisaka (Kurosawa’s The Quiet Duel / Shizukanaru Ketto). In 1950, he replaced future director Tai Kato as trailer director on Rashomon. This assignment gave him the opportunity to visit the set several times, especially around the Komyo-ji Buddhist Temple, where a high-tension line was used to feed the lighting and electrical equipment required to shoot outdoors and record a synchronized sound track. Morita recounted that Kurosawa had to replace unavailable Mitchell cameras with Eyemo cameras (used during the war by combat cameramen) in order to shoot the scenes with Takashi Shimura. He also remembered how Buddhist monks from the nearby temple got angry after Kurosawa and his crew started to fell bamboo trees for the sake of the shoot.

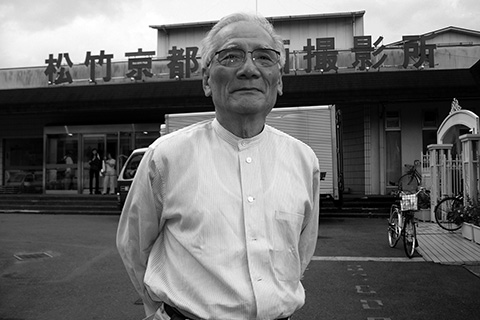

Fujio Morita outside Shochiku studios in Kyoto

At the time, in the early 1950s, it was still impossible for Morita to buy an exposure meter, which cost up to thrice his monthly salary. In 1955, he worked as a focus puller on Mizoguchi’s Taira Clan Saga (Shin Heike Monogatari). He was promoted to director of photography in 1962, on Mitsuo Murayama’s Yamaotoko no Uta, and earned the Miura Prize in 1965 for Daimajin, on which he filmed the "Japanese Golem" at a rate of up to 36 frames per second, in order to create very subtle slow motion effects.

Among the fastest directors in exercise at Daiei was Kazuo Mori, known for Secrets of a Court Masseur (Shiranui Kengyo, 1960), with Shintaro Katsu, as well as A Certain Killer (Aru Koroshiya, 1967) with Raizo Ichikawa. Mori tolerated Morita’s slowness to a degree, for he was still young. But when Morita, during a night of drinking, had the nerve to tell Mori that he was shooting way too fast, the director blew his top and told the fledgling assistant that he was fired and not allowed to be part of his team anymore. However, the two men buried the hatchet a few years later, with Morita lensing such Mori films as Spy on the Masked Car (Ano Shishosha o Nerae, 1967) and Zatoichi At Large (Zatoichi Goyo-tabi, 1972).

In 1969, Shintaro Katsu urged Morita to take on photography of Hideo Gosha’s Hitokiri (Tenchu). Though Morita did not care much about Gosha as a director, due to his background in television, he had been impressed with Goyokin (1969) and felt anxious to film such stars as Yujiro Ishihara, Tatsuya Nakadai, and writer-actor-director Yukio Mishima in what was a last-ditch film effort to stop Daiei’s downhill slide. However, Morita and Gosha hit it off perfectly, and given that the rule at Daiei was to put directors and cinematographers on an equal footing, Morita found himself in charge of continuity throughout the film, while Gosha could focus on directing his stellar cast.

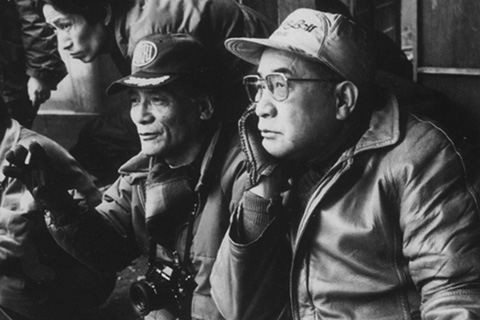

Fujio Morita (left) with Hideo Gosha

The difference between Goyokin and Hitokiri in terms of telephoto lenses and zooming was due mostly to the fact that Fujio Morita did not have the new generation of Panavision lenses at his disposal, but the old Mitchell cameras - which his Toho-based colleague Kozo Okazaki compared to heavy propeller planes. "I could not have done an über-Goyokin," Morita once admitted. "Mechanically speaking, it was still difficult to zoom in and out with the cameras we had, even more so with the Cinemascope format." However, Morita made up the lack of lens smoothness with frame composition skills, and, like Kozo Okazaki, a willingness to experiment with what he had at his disposal. This is how he tried out a difficult reticulation effect in Izo Okada’s death scene. Perfectly poised between film studio tradition and modernity, Morita created a cartoonish effect in the first part of Okada’s great marathon race, by which the character, played by Shintaro Katsu, would leave small clouds of dust in his wake, like characters running in manga and Japanese animation. Furthermore, though Morita was still a young DP, he was allowed to do retakes of dreamlike (or nightmarish) scenes that proved difficult to handle properly in the later part of the film.

Although Hitokiri was a commercial hit and won several awards, it could not fix Daiei’s finances. The Kyoto-based studio went bankrupt in 1971. Morita and set decorator Yoshinobu Nishioka then set up an association called Eizo Kyoto, which included directors and technicians of the former Kyoto-based Daiei company. They all resumed work on Shintaro Katsu’s films and TV series, especially the long-running Zatoichi saga.

Like Daiei assistant director Mitsuaki Tsuji and the editors who worked for the actor-turned-director, Fujio Morita had a difficult relationship with Shintaro Katsu, who had decided to discard traditional film grammar in favor of a free, handheld camera style and extensive use of zooming. This was much to Morita’s chagrin, for the rational DP always cared about shot to shot continuity and master shots, which Katsu as a director simply did not care about. The two men almost butted heads on the set of Zatoichi in Desperation (Shin Zatoichi Monogatari Oreta Tsue, 1972).

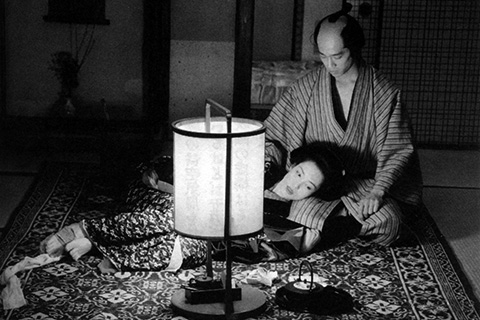

Still, Morita lensed several episodes of the Zatoichi TV series with great success, including the much-appreciated A Lover's Suicide Song. This visually stunning 23d episode from Season 1, about Zatoichi helping a goze (blind shamisen player) played by Ruriko Asaoka, was directed by Shintaro Katsu and rooted in a more traditional film language which highlighted Morita’s tremendous composition skills in snowy landscapes, his ability to match, light-wise, interiors and exteriors in a single shot, and his perfectly timed use of close-ups. Seiichi Sakai, who used to assist editor Toshio Taniguchi, told me how this particular episode was hailed as a minor masterpiece and was much discussed by audiences and critics alike. This kind of top-notch quality also helped Katsu feel that he could still maintain the highly professional standards of movie production in his TV creations, with the precious help of such technicians as Yoshinobu Nishioka and Fujio Morita, and directors like Kenji Misumi, though this method would prove too money and time-consuming for the fast demands of the TV market.

Zatoichi: A Lover's Suicide Song

After having made a few feature films himself, Katsu eventually told Morita how he regretted discarding Daiei’s film grammar and Kenji Misumi’s aesthetic legacy in favour of mostly anarchic visuals. "He started to measure up his own films by the standards of Misumi’s work and felt that his were simply below par," Morita said.

In 1973, Morita, despite some back problems, lensed Kenji Misumi’s Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart In The Land Of Demons (Kozure Okami Meifumado). The two men knew each other well since the Daiei days, and had a smooth collaboration, though the director could be overly harsh with actresses. Morita remembers how young actress Kaori Momoi (in a wedding dress) angrily left the set of a TV series because Misumi would have her repeat a scene countless times. Baby Cart gave Morita the opportunity to shoot what may be the best chanbara scene in his career. He experimented again with film speed in the sword fights and action scenes, with a rate of either 36 frames per second, in order to have slow-motion effects, or 18 frames per second, so as to speed up some movements (this effect was called motion nusumi). Morita also liked to use the nakanuku effect, which meant removing several frames in the editing of an action scene. Morita did all this in order to go beyond photorealism and give the film a kind of manga-like stylization, as in Hitokiri.

After Kenji Misumi’s death in 1975, Morita still had his hands full with the Zatoichi series, although Katsu Production was becoming weaker and weaker. After one more television series and a film shot in Tokyo, he had a chance encounter with Hideo Gosha, who was then in Kyoto looking for a DP for his upcoming renaissance film, Onimasa. Morita quickly accepted the offer and urged the producers to start production as quickly as possible, for the script called for hot, summer scenes which had to be shot before the season ended and before actress Masako Natsume was scheduled to undergo surgery (she was then very ill and would die in 1985). Morita said how he always remembered the Onimasa shoot for the talent of the late Natsume, who was the only actress to make him weep on the set, behind the lens of his camera, in the scene where her character had to cry when reunited with her father, played by Tatsuya Nakadai. After the commercial success of Onimasa, Gosha and Morita went on to make 11 more films together, though the latter and his associate, set decorator Yoshinobu Nishioka, were initially reluctant to work for Toei – Morita once said how he hated filming Yakuza Wives (Gokudo no Onnatachi, 1986), though he was bent on not making the usual Toei yakuza flick. Thanks to the skilled duo, Gosha was able to focus on directing his actors, and even more so his actresses, as passionately as he wished, while Morita and Nishioka were allowed to experiment with sets and visuals.

Tokyo Bordello

For Tokyo Bordello (Yoshiwara Enjo, 1987), Morita filmed through gauze in order to emulate the soft style of Shinichi Saito’s paintings. For Four Days of Snow and Blood (Ni-ni-roku, 1989), he used a bleach bypass to create a de-saturated effect and show a world devoid of "human colours." Morita was especially proud of Gosha’s last film, The Oil-Hell Murder (Onnagoroshi Abura no Jigoku, 1992). The director was then terminally ill, and Morita did his very best, for instance in the shot where an embarkation floats towards a hut on a lake, a shot which Morita cited above all others in the book Interviews with 40 Japanese Cameramen by Takeshi Yamaguchi (Heibonsha, 1997). Morita also filmed what may qualify as the greatest fire scene in Japanese cinema (together with the castle scene in Kurosawa’s Ran) in Tokyo Bordello, namely the recreation of the great inferno that destroyed the pleasure quarters of Shin Yoshiwara, back in 1911. The 150-metre long set was thus burnt to the ground in front of up to seven cameras.

Tokyo Bordello

All in all, Fujio Morita helped Gosha mature as a director by taking on the arduous task of controlling shot-to-shot continuity, which the director often overlooked on account of his TV background. Morita felt that it was the DP’s task to tell the director when a close-up or a zoom was needed. He felt that he was the "eyes of the audience" and that, in their later days, both Kurosawa and Gosha forgot about the virtues of close-up in favor or wide shots that looked too much like paintings. Close-ups, he felt, were essential in giving film narrative more emotive power and physicality, which is why Morita would slowly track or zoom forward towards the actors in order to get closer to the expression of their emotions and physical reactions.

In his later days, Fujio Morita started to give classes and lectures, and he liked to stress the fact that he valued films that, beyond fantasy, possessed a real socio-historical content, very much like Tokyo Bordello. He would often remind film students when and how, for instance, Japanese women had gained the right to vote. Having grown up in a Kyoto area where there were real geisha and poor prostitutes, Morita stressed that he greatly valued Gosha’s unblinking approach to "the realities of life," such as sexuality, contraception, venereal diseases, illnesses, insanity, and death. Morita also stressed how Gosha was probably the only director ever to rehearse sex scenes with a male assistant in order to ease his actresses’ anxiety.

Fujio Morita deemed it impossible to still make good Japanese costume films, because the orthodoxy of the genre had simply died away and directors had no great knowledge in terms of its aesthetics, history, and Japanese history as a whole. Maybe, like Kurosawa, he lamented the fact that the younger generations of directors would no longer make films based on great literary classics and historical subjects, but rather flavor-of-the-month TV dramas and comic books.

The Oil Hell Murder

In 2012, Fujio Morita was called upon to help supervise for Imagica (formerly Toyo Laboratories) the 4K grading and restoration of Gate of Hell, a film that retains Daiei’s aesthetic legacy. (Morita had filmed Hideo Gosha’s Death Shadows / Jittemai in 1986, the last film ever shot at Daiei’s Kyoto-based studio.) "Fortunately, legendary front-line cinematographer Fujio Morita, who was a camera assistant on Gate of Hell, understood the intention of art and color of the film, and was able to supervise the grading to revive the vibrant look," said Imagica’s technical advisor Norimasa Ishida.

The late Seiichi Ichiko, who was Shintaro Katsu’s assistant on the Zatoichi TV series, once said that there were three great directors of photography working at the Kyoto Daiei studio: "Kazuo Miyagawa, Chikashi Makiura and the younger Fujio Morita. Miyagawa was classic and Makiura very artistic, while Morita had a great visual flair. Morita was especially adroit with the long telephoto lens, slow forward-backward zooming and color matching shots." All in all, Fujio Morita was one of the last great Daiei cameramen, whose work was perfectly poised between film studio tradition and aesthetic innovation. Let us hope that his legacy will not be lost to the younger generations of DPs and directors, so as to allow them to make the kind of Japanese cinema that we love, challenging in both its aesthetics and socio-historical commentary.

(Special thanks to Seiichi Sakai, Fujio Morita and Yoshinobu Nishioka)