The World of Yasujiro Ozu

- published

- 8 December 2003

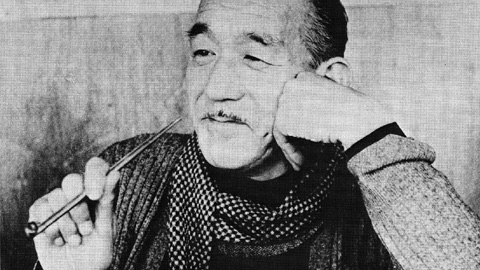

December 12th 2003 is a significant date for Japanese cinema. It is the centenary of the birth of a man considered both at home and abroad to be "the most Japanese of all directors": Yasujiro Ozu, director of such classics as I Was Born, But…, Late Spring, Floating Weeds and of course Tokyo Story. In a remarkable piece of symmetry in keeping with the immaculate nature of his oeuvre, it also marks the 40th anniversary of his death due to throat cancer on his 60th birthday in 1963.

In a poll of over 250 critics, writers and directors from all around the world conducted by the British Film Institute's Sight and Sound magazine in 2002, Ozu's Tokyo Story was ranked as the 5th best film of all time. It is the most famous work of a director who, over a career which spanned thirty-five years, saw him continuously refining his chosen genre of the gendai-geki, or contemporary drama, elevating it to the realm of high art.

Curiously, at the time of writing, out of the thirty-six films of his which are still extant in complete or near complete form (most of his silent films are now lost, including his 1927 debut Sword of Penitence / Zange no Yaiba, his only ever jidai-geki, or period piece), Tokyo Story is the only one which is currently available in the UK, on a VHS edition first released almost ten years ago. [Update: a situation markedly improved since, with the release of several DVD box sets.]

Such is the paradoxical situation Ozu now finds himself in. Long lauded by critics and film buffs, to the general viewer Ozu's work is still considered as rather highbrow, slow-moving and lacking the more obvious commercial potential of other directors from the period such as Akira Kurosawa or Kenji Mizoguchi. But looking at works such as I Was Born, But…, now over 70 years old, the modern viewer will be struck by the freshness, the honesty and the humour which marked out the very best of the director's films.

Perhaps one of the reasons for this lack of contemporary popularity is that Ozu's films are almost always referred to in terms of their style, rather than their content. This is perhaps unsurprising, not only given that this style, with the action unfolding in a series of flattened tableaux shot from a low angle, is so unique, but also that Ozu himself increasingly refused to dramatise his stories, opting to instead to portray the minutiae of everyday life with the emphasis on character and nuance. Key dramatic incidents were often leapfrogged over, in adherence to the modernist principle that audiences were already familiar with them, and that in themselves they added little to the story.

Such an approach runs counter to the classic linear narrative model popularised by Hollywood, which has led many writers, such as Noel Burch in his To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema (1979), to see Ozu's films in oppositional terms to Western cinema and belonging to a more uniquely Japanese tradition.

The truth is that Ozu himself was profoundly influenced by American cinema. Stranded in Singapore at the time of Japan's surrender to the Allied Powers on August 15th 1945, he spent days watching American films that had been captured by the Japanese Army, and expressed great admiration for such seminal works as Orson Welles's Citizen Kane and Alfred Hitchcock's Rebecca. In the early days he was also influenced by the silent films of Ernst Lubitsch, and included a fragment of If I Had a Million in his 1933 film Woman of Tokyo.

Tokyo Story was Ozu's first film to be released in the West, winning the First Sutherland Cup as the best film to be played at the British Film Institute in 1958. The first successful commercial release was of his final work, An Autumn Afternoon, which played in Paris in 1962, but it was when Donald Richie persuaded Shochiku to allow him to take a number of his films to the Berlin Film Festival in 1963 that Ozu's reputation really began to spread.

Paul Schrader's book Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson and Dreyer followed in 1972, and a more complete analysis of his works came in 1974 in the form of Richie's Ozu: His Life and His Films. This was followed later by David Bordwell's Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema.

To this list we can also add a newly translated work by Kiju Yoshida, Ozu's Anti-Cinema, which throws Ozu's body of work into a whole new light. Aside from being the first Japanese look at his work to be translated into English, the book is of double interest due to the background of its writer. Yoshida was one of the most significant filmmakers of the Japanese New Wave movement of the 1960s, with his most famous work being Eros Plus Massacre in 1969. The agenda of the New Wave was to rail against established studio-based filmmaking practices, with their conservative focus on tradition and family values, to bring the focus to youth and politics and to capture the dynamism of a society in a state of flux. Ozu, by far the most popular director of his day, was seen to embody everything wrong with the contemporary filmmaking culture, and thus became a suitable target for the critical writings of the New Wave filmmakers.

Yoshida's book begins anecdotally with his two meetings with the master director. The first was shortly after Yoshida had published an article criticising Ozu's The End of Summer (1961) for trying to cater to a younger audience that he didn't properly understand. At a party after the publication of this piece, Ozu silently snubbed Yoshida, ending their meeting with the characteristically oblique comment "After all, film directors are like prostitutes under a bridge, hiding their faces and calling their customers".

Their second meeting was at Ozu's deathbed, when Ozu's parting words to Yoshida were "Cinema is drama, not accident". Yoshida's book sees him pondering Ozu's last words to him decades after the incident, using them as a basis to revisit and reinterpret the director's films. The end results are a fascinatingly readable reappraisal of Ozu's life and philosophy from a director who initially came from a diametrically opposed viewpoint, which attempts to get to the heart of just why Ozu's films are so enduringly powerful to this day.

Despite Ozu's reputation as one of the grand masters of 20th-century world cinema, over the past few years, very little of his work has actually been available. Fortunately the situation is about to change. A number of Ozu retrospectives have occurred around the world, including ones at the New York Film Festival and at the Berlin International Film Festival.

To commemorate this 100th anniversary of his birth, Shochiku in Japan have also just put out a complete DVD boxed set of his works, though with a characteristic myopia to what goes on in the rest of the world, have neglected to include subtitles. Nevertheless, a number of his works have been released in Hong Kong by Panorama, the first being Late Autumn, and Criterion have just released Tokyo Story in the US, with the promise of many more to follow. Stone Bridge Press have also just published a newly translated version of the script of this same film by Donald Richie.

Indeed, it couldn't be a better time to revisit the works of one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. In order to help you through the tricky task of where to find an entry point into this remarkable oeuvre, Midnight Eye gives an overview of some of his finest works.

I Graduated, But… (Daigaku wa Deta keredo, 1929)

- Cast

- Utako SUZUKI, Minoru TAKADA, Kinuyo TANAKA, Kenji OYAMA, Takeshi SAKAMOTO

Tetsuo Nomoto (Takada) is a recent college graduate who, like many educated young men at the time, is having a hard time finding work. He attends a job interview and is offered a position as office receptionist, but turns it down in a fit of diploma-inspired pride. When his mother (Suzuki) and fiancée Machiko (a youthfully charming Tanaka) unexpectedly move in, Tetsuo has to pretend that he is employed, so he spends his mornings and afternoons out of the house, playing ball with the boys at a nearby park. Soon mom moves out, and Tetsuo admits to his new bride that his "job" was only an attempt to keep his mother from worrying. The two quarrel, and that night Tetsuo visits a café with a friend only to discover that Machiko has been working there as a waitress without his knowledge. The trauma of finding his wife employed as a café waitress strengthens Tetsuo's resolve to find a job, and he returns to the previous company to beg for whatever work is available. Satisfied with Tetsuo's newfound humility, the gentlemen offer him a position as a full company employee.

Tetsuo Nomoto (Takada) is a recent college graduate who, like many educated young men at the time, is having a hard time finding work. He attends a job interview and is offered a position as office receptionist, but turns it down in a fit of diploma-inspired pride. When his mother (Suzuki) and fiancée Machiko (a youthfully charming Tanaka) unexpectedly move in, Tetsuo has to pretend that he is employed, so he spends his mornings and afternoons out of the house, playing ball with the boys at a nearby park. Soon mom moves out, and Tetsuo admits to his new bride that his "job" was only an attempt to keep his mother from worrying. The two quarrel, and that night Tetsuo visits a café with a friend only to discover that Machiko has been working there as a waitress without his knowledge. The trauma of finding his wife employed as a café waitress strengthens Tetsuo's resolve to find a job, and he returns to the previous company to beg for whatever work is available. Satisfied with Tetsuo's newfound humility, the gentlemen offer him a position as a full company employee.

I Graduated, But… is a pleasant drama with the sprinklings of (post-) college humor that are common to Ozu's earlier work. But with only a fraction of the film's footage in existence today it's difficult to judge the overall quality of the film and "Ozu-ness" of the technique. Luckily the surviving fragment has been released on video in Japan, and at least one version features the familiar and enlightening voice of Shinsui Matsuda, whose benshi narration sutures the film's narrative handicap into a 15-minute whole. Ozu's colleague and an excellent director in his own right, Hiroshi Shimizu, who was originally planned as the director for this film as well, wrote the original story. [MA]

Tokyo Chorus (Tokyo no Gassho, 1931)

- Cast

- Tokihiko OKADA, Emiko YAGUMO, Tatsuo SAITO, Choko IIDA, Hideo SUGAWARA, Hideko TAKAMINE

Handsome cinema star Okada plays Shinji Okajima, a young parent and slightly stubborn employee at a Tokyo insurance company. When Shinji complains to his superiors about the unjust firing of an elderly co-worker, he is dismissed as well. His daughter (Takamine) falls ill one day, and the unemployed Shinji is forced to pawn the family's clothes in order to pay for medical treatment. Heading towards financial collapse, Shinji bumps into his teacher from junior high school, Mr. Omura (Saito). Omura has opened a small Western foods restaurant (featuring Mrs. Omura's specialty - curry and rice) and he invites Shinji over. The teacher offers his former student a job passing out advertisements for the restaurant when he hears of his financial problems. Shinji accepts, but when his wife (Yagumo) sees him handing out flyers on the street, she is frustrated and embarrassed that her husband has resorted to such a lowly task. Soon afterwards Shinji helps to organize a class reunion and celebration for Mr. Omura at the restaurant, and during the festivities the ex-student receives a letter with the news that he's been hired as an English teacher in a rural school far from Tokyo (thanks to Omura's help). The final scene turns to bittersweet sorrow as Shinji realizes he must bid farewell to his old teacher and school friends. As Shinji and Omura wipe away their tears, the classmates and teacher sing a final chorus together.

Handsome cinema star Okada plays Shinji Okajima, a young parent and slightly stubborn employee at a Tokyo insurance company. When Shinji complains to his superiors about the unjust firing of an elderly co-worker, he is dismissed as well. His daughter (Takamine) falls ill one day, and the unemployed Shinji is forced to pawn the family's clothes in order to pay for medical treatment. Heading towards financial collapse, Shinji bumps into his teacher from junior high school, Mr. Omura (Saito). Omura has opened a small Western foods restaurant (featuring Mrs. Omura's specialty - curry and rice) and he invites Shinji over. The teacher offers his former student a job passing out advertisements for the restaurant when he hears of his financial problems. Shinji accepts, but when his wife (Yagumo) sees him handing out flyers on the street, she is frustrated and embarrassed that her husband has resorted to such a lowly task. Soon afterwards Shinji helps to organize a class reunion and celebration for Mr. Omura at the restaurant, and during the festivities the ex-student receives a letter with the news that he's been hired as an English teacher in a rural school far from Tokyo (thanks to Omura's help). The final scene turns to bittersweet sorrow as Shinji realizes he must bid farewell to his old teacher and school friends. As Shinji and Omura wipe away their tears, the classmates and teacher sing a final chorus together.

One of the highest peaks of Ozu's prewar work, Tokyo Chorus won the number three position on the Kinema Junpo Best Ten list of 1933. This one too mixes Ozu's usual humor, drama and tragedy, but somehow the overall effect leaves something to be desired. (A benshi, perhaps?) It does, however, exhibit a wonderful playful spirit in the photography, with shapes and compositions that draw the viewer into some very enjoyable visual "jokes". One particular highlight is the payday sequence at the office early in the film. [MA]

Woman of Tokyo (Tokyo no Onna, 1933)

- Cast

- Yoshiko OKADA, Ureo EGAWA, Kinuyo TANAKA, Shinyo NARA

Possibly one of the more satisfyingly grim features in Ozu's early career, Woman of Tokyo is certainly one of my highest recommendations from the director's pre-war work. Ryoichi (Egawa) lives with his older sister Chikako (Okada) in a small home in Tokyo. Ryoichi is used to his sister's habit of staying out late at night for work, and is grateful for her financial support. He has a young girlfriend Harue (Tanaka), and the two look forward to getting married one day… until tragedy suddenly strikes. Harue's father (Nara) informs her that Chikako is rumoured to be working as a prostitute - the kind of news that could instantly demolish any chance of marriage with Ryoichi.

Possibly one of the more satisfyingly grim features in Ozu's early career, Woman of Tokyo is certainly one of my highest recommendations from the director's pre-war work. Ryoichi (Egawa) lives with his older sister Chikako (Okada) in a small home in Tokyo. Ryoichi is used to his sister's habit of staying out late at night for work, and is grateful for her financial support. He has a young girlfriend Harue (Tanaka), and the two look forward to getting married one day… until tragedy suddenly strikes. Harue's father (Nara) informs her that Chikako is rumoured to be working as a prostitute - the kind of news that could instantly demolish any chance of marriage with Ryoichi.

Harue decides to tell her unknowing boyfriend. When she breaks the news Ryoichi reacts horribly, kicking Harue out of his home and breaking off their relationship. That night Ryoichi confronts Chikako about her activities and she confesses, saying that it was all to help Ryoichi get through school. Ryoichi however is unable to accept his sister's sacrifice and he runs out into the night. Chikako visits Harue the next day and the two fret over the decision to spill the beans to Ryoichi, until Harue receives a telephone call which, in the film's final devastating blow, informs her that Ryochi, unable to bear the reality of his sister's night work, has taken his own life.

While on the one hand successfully exploiting the 1930s trope of the so-called modern girl's social depravity and descent into decadence in the (sexual) working world, Woman of Tokyo mixes the tragic fate of the three young adults with a brilliantly evocative use of "abstractly" communicative imagery. Especially curious are a sequence that visually quotes a Lubitsch film when Ryoichi and Harue go to the movies, the odd matching of clocks on the wall between two locations when Harue receives the horrible telephone call, and the film's final, bleak travelling shot along the city sidewalk following the exit of the two police investigators, who have just amplified the horror with their own utter ambivalence. This one is all the more interesting for the treatment it received in Burch's ambitiously theoretical To the Distant Observer, and the attentive rebuttal that analysis inspired in Bordwell's Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema nine years later. [MA]

Record of a Tenement Gentleman (Nagaya Shinshiroku, 1947)

- Cast

- Choko IIDA, Takeshi SAKAMOTO, Reikichi KAWAMURA, Tomihiro AOKI

Record of a Tenement Gentleman is the relatively short (by Ozu standards) but very likeable tale of a middle-aged widow unwillingly burdened with a stray child. The boy, who lost his father in the city ruins, says little and simply follows her around wherever she goes. Annoyed by the boy's constant presence, the woman puts him to work at various menial tasks and calls him an idiot for the slightest thing he does wrong.

Record of a Tenement Gentleman is the relatively short (by Ozu standards) but very likeable tale of a middle-aged widow unwillingly burdened with a stray child. The boy, who lost his father in the city ruins, says little and simply follows her around wherever she goes. Annoyed by the boy's constant presence, the woman puts him to work at various menial tasks and calls him an idiot for the slightest thing he does wrong.

Made and set in the immediate post-war (the city is shown as a deserted ghost town, full of litter on the breeze but no people) Ozu's concerns with the effect of the reconstruction on family life are already present here. In this case, however, the widow's treatment of the boy changes from disregard to compassion and the film ultimately expresses a strong sense of hope and solidarity.

Record of a Tenement Gentleman is rendered quite irresistible by its two leads, the cranky Iida and the wordlessly endearing Sakamoto. The director's remarkable talent for composition is very much in evidence here, particularly in the beach sequences. [TM]

Late Spring (Banshun, 1949)

- Cast

- Chishu RYU, Setsuko HARA, Haruko SUGIMURA, Jun OSAMI, Yumeji TSUKIOKA

Late Spring is perhaps the archetypal Ozu story. A widowed college professor named Shukichi (Ryu) lives with his daughter Noriko (Hara) in the city of Kamakura. Due to a lack of eligible men available during the war, Noriko is slightly past marrying age, a fact which is of great concern to her father. When she hears of one of her father's friends remarrying, she disapproves, but her father feels that Noriko is only remaining unmarried because of him. In order to prompt her into marriage, the father pretends he is remarrying, and the two partake a final trip together to Kyoto. When they return, Noriko is married, leaving the father to live all alone in the family house.

Late Spring is perhaps the archetypal Ozu story. A widowed college professor named Shukichi (Ryu) lives with his daughter Noriko (Hara) in the city of Kamakura. Due to a lack of eligible men available during the war, Noriko is slightly past marrying age, a fact which is of great concern to her father. When she hears of one of her father's friends remarrying, she disapproves, but her father feels that Noriko is only remaining unmarried because of him. In order to prompt her into marriage, the father pretends he is remarrying, and the two partake a final trip together to Kyoto. When they return, Noriko is married, leaving the father to live all alone in the family house.

Donald Richie states that this is the first film in which what is now recognised as Ozu's unique style came to the fore. The plot, which is similar in set up to that of Early Summer (Bakushu, 1951) and An Autumn Afternoon (Samma No Aji, 1962), is condensed to little more than a series of incidents, and the editing style, complete with the famous low camera angles and non-matching eyeline shots, is slow but assuredly paced. Even the names of the characters would be used again in his later films to represent specific character archetypes - for example, in Tokyo Story, Hara would again play a vibrant single daughter past usual marrying age named Noriko, and Ryu would reprise his role as the patient and philosophical patriarch Shukichi. The picture composition is perfect, as we are led through a series of locations, which are a mixture of Western-styled Ginza cafés and the more traditional family seat in Kamakura, Japan's ancient capital in the period of the same name (1188-1333) - one hour south of Tokyo and close to Shochiku's Ofuna studios, where many of Ozu's films were shot. With Noriko's modern Western clothes at odds with the kimonos of the other women that surround her, including her aunt, Ozu's poignantly portrays the inevitable break-up of the family as the lifestyles of the two generations become necessarily pushed further apart. [JS]

The Munakata Sisters (Munakata Shimai, 1950)

- Cast

- Kinuyo TANAKA, Hideko TAKAMINE, Ken UEHARA, Chishu RYU, So YAMAMURA

Ozu's first film for Shintoho studios veers towards melodrama in a story of two sisters in love with the same man. Both bar owner Setsuko and her younger sister Minako have feelings for Hiroshi, a dealer in European antiques. Minako, who adores anything Western, is immediately drawn to his smart suits and sophistication, but discovers that Setsuko, who is married to an ailing alcoholic, once had an affair with Hiroshi and that the two still carry a torch for each other.

Ozu's first film for Shintoho studios veers towards melodrama in a story of two sisters in love with the same man. Both bar owner Setsuko and her younger sister Minako have feelings for Hiroshi, a dealer in European antiques. Minako, who adores anything Western, is immediately drawn to his smart suits and sophistication, but discovers that Setsuko, who is married to an ailing alcoholic, once had an affair with Hiroshi and that the two still carry a torch for each other.

Ozu renders the sibling rivalry not purely in melodramatic terms, but portrays Minako as a woman who embraces Western influences with such abandon as to dismiss anything to do with her own culture. She loves the trinkets Hiroshi brought from France, but hates his Buddha statuettes. Her assumption of Western ways also make her manners less reserved than those around her, resulting in very overt displays of emotion in the clash with her sister and family, which makes for an interesting change in comparison with much of Ozu's work. [TM]

Tokyo Story (Tokyo Monogatari, 1953)

- Cast

- Chishu RYU, Chieko HIGASHIYAMA, Setsuko HARA, So YAMAMURA, Haruko SUGIMURA, Kyoko KAGAWA, Kuniko MIYAKE, Shiro OSAKA, Eijiro TONO, Nobuo NAKAMURA, Teruko NAGAOKA

Aging couple Shukichi (Ryu) and Tomi (Higashiyama) leave their home by the Inland Sea to visit their son Koichi (Yamamura), a doctor, and his family living in Tokyo. The younger generation are too busy to entertain them however, dispatching them off to a hot spring resort in Izu for a few days to get them out from under their feet. The most sympathetic of the youngsters is 28 year-old Noriko (Hara), who is not even a real blood relation, and a member of the family only due to her marriage to their son Shoji, who was killed during the war. Tomi urges her to remarry.

Aging couple Shukichi (Ryu) and Tomi (Higashiyama) leave their home by the Inland Sea to visit their son Koichi (Yamamura), a doctor, and his family living in Tokyo. The younger generation are too busy to entertain them however, dispatching them off to a hot spring resort in Izu for a few days to get them out from under their feet. The most sympathetic of the youngsters is 28 year-old Noriko (Hara), who is not even a real blood relation, and a member of the family only due to her marriage to their son Shoji, who was killed during the war. Tomi urges her to remarry.

Reducing Tokyo Story to a straightforward synopsis does little to indicate the power and beauty of the best known of Ozu's works. With drama kept to a bare minimum, Ozu's film rests on nuance, observation and character, as well as the unobtrusively immaculate nature of his celebrated technique that has had him labelled as "the most Japanese of directors". Though the long running time and slow pacing are not going to appeal to all audiences, Tokyo Story is a true classic of world cinema. [JS]

Early Spring (Soshun, 1956)

- Cast

- Ryo IKEBE, Chikage AWASHIMA, Takako FUJINO, Keiko KISHI, Kuniko MIYAKE, Chishu RYU, Haruko SUGIMURA, Teiji TAKAHASHI, So YAMAMURA, Masami TAURA, Kumeko URABE

Marital infidelity and the lot of the disillusioned salaryman form the backdrop of Ozu's prescient follow-up to Tokyo Story, as young white-collar worker Shoji Sugiyama (Ikebe) falls for the charms of vampish office associate Chiyo (Kishi), all but ignoring his wife Masako (Awashima) at home. A slight departure from his work during the period, the longest of Ozu's post-war films sees his focus shifting away from the home towards the office environment, portraying it almost as a surrogate family as Shoji opts to spend more time drinking with his co-workers than in the heart of a marriage that has grown increasingly cold since the death of their only child several years before. In accordance with the subject matter, Early Spring lacks the warmth of the best known of the director's work, the domestic scenes noticeably empty of life, but whilst the film could easily be seen as a critique of Japan's increased modernisation, Ozu's non-polemical approach instead evokes the pathos of an intelligent young man at odds with his environment, trapped in a lifestyle in which the dreams of his past have been long forgotten, as he suggests that these two separate worlds of work and family are irreconcilable. [JS]

Marital infidelity and the lot of the disillusioned salaryman form the backdrop of Ozu's prescient follow-up to Tokyo Story, as young white-collar worker Shoji Sugiyama (Ikebe) falls for the charms of vampish office associate Chiyo (Kishi), all but ignoring his wife Masako (Awashima) at home. A slight departure from his work during the period, the longest of Ozu's post-war films sees his focus shifting away from the home towards the office environment, portraying it almost as a surrogate family as Shoji opts to spend more time drinking with his co-workers than in the heart of a marriage that has grown increasingly cold since the death of their only child several years before. In accordance with the subject matter, Early Spring lacks the warmth of the best known of the director's work, the domestic scenes noticeably empty of life, but whilst the film could easily be seen as a critique of Japan's increased modernisation, Ozu's non-polemical approach instead evokes the pathos of an intelligent young man at odds with his environment, trapped in a lifestyle in which the dreams of his past have been long forgotten, as he suggests that these two separate worlds of work and family are irreconcilable. [JS]

Good Morning (Ohayo, 1959)

Read the full review

Floating Weeds (Ukigusa, 1959)

- Cast

- Ganjiro NAKAMURA, Machiko KYO, Ayako WAKAO, Hiroshi KAWAGUCHI, Haruko SUGIMURA, Hitomi NOZOE, Hikaru HOSHI, Yosuke IRIE, Hideo MITSUI

A travelling theatrical troupe visits a small seaside town for a series of performances. The leader, Komajuro Arashi (Nakamura), uses the trip as an excuse to visit his ex-lover Oyoshi (Sugimura) and their son, Kiyoshi (Kawaguchi). Kiyoshi, now a young adult, has always been told that Komajuro is his mother's brother, and his "uncle's" visits have been only sporadic over the years. Komajuro and Oyoshi both hope to tell Kiyoshi the truth some day, but for now Komajuro simply wants to spend as much time with his family as possible. Alas, the actor's current mistress and the lead actress in the troupe, Sumiko (Kyo), hears rumors from the cast about the boss visiting another woman and becomes intensely jealous. She convinces her younger colleague Kayo (Wakao) to seduce Oyoshi's son and disrupt family affairs. However, while the troupe steadily loses business and money waiting for Komajuro to pack up and leave town, Kayo and Kiyoshi fall for each other. Komajuro disbands the troupe, and when he hears of Sumiko's actions he abandons her as well. Finally, in a tense argument between mother, father and son, Kiyoshi learns what he suspected all along, but he rejects his "father's" sudden decision to rejoin the family. Kiyoshi and Kayo settle in town, the dejected Komajuro and Sumiko leave together on a train, and distraught Oyoshi finds herself left in the dust, as she always was.

A travelling theatrical troupe visits a small seaside town for a series of performances. The leader, Komajuro Arashi (Nakamura), uses the trip as an excuse to visit his ex-lover Oyoshi (Sugimura) and their son, Kiyoshi (Kawaguchi). Kiyoshi, now a young adult, has always been told that Komajuro is his mother's brother, and his "uncle's" visits have been only sporadic over the years. Komajuro and Oyoshi both hope to tell Kiyoshi the truth some day, but for now Komajuro simply wants to spend as much time with his family as possible. Alas, the actor's current mistress and the lead actress in the troupe, Sumiko (Kyo), hears rumors from the cast about the boss visiting another woman and becomes intensely jealous. She convinces her younger colleague Kayo (Wakao) to seduce Oyoshi's son and disrupt family affairs. However, while the troupe steadily loses business and money waiting for Komajuro to pack up and leave town, Kayo and Kiyoshi fall for each other. Komajuro disbands the troupe, and when he hears of Sumiko's actions he abandons her as well. Finally, in a tense argument between mother, father and son, Kiyoshi learns what he suspected all along, but he rejects his "father's" sudden decision to rejoin the family. Kiyoshi and Kayo settle in town, the dejected Komajuro and Sumiko leave together on a train, and distraught Oyoshi finds herself left in the dust, as she always was.

Ozu's first film outside of Shochiku studios was The Munakata Sisters at Shintoho in 1950. Floating Weeds was the second, and it was the only film Ozu produced through Daiei. Somehow the presence of the Daiei leads - Nakamura, Kyo, Wakao, Kawaguchi, Nozoe and other actors we probably identify more easily with Masumura, Ichikawa or even Kurosawa - adds a breath of fresh air into the chemistry on the screen, a breath that comes out in a truly Ozu-worthy flowering of bad words, sexual innuendo and confrontation. Compositionally, the color photography by Daiei's Kazuo Miyagawa (Rashomon) is impeccable, and one marvels at Ozu's own comfort and fluency in and out of his system of rhythmical editing and 180 degree cuts. This is without a doubt one of the director's very best films, enough to convince the viewer that film - while maintaining the full potency of Ozu's fascinating and unique system - can still be "drama" after all. Based on Ozu's 1934 Story of Floating Weeds (Ukigusa Monogatari). [MA]

The End of Summer (Kohayagawake no Aki, 1961)

- Cast

- Ganjiro NAKAMURA, Setsuko HARA, Yoko TSUKASA, Michiyo ARATAMA

The patriarch of the Kohayagawa family of sake brewers leaves the running of his ailing business to his juniors, after a chance meeting with his former mistress. He regularly travels to Kyoto to see her and the daughter who might be his own. His three legitimate daughters back home, however, don't take too kindly to his schemes once they discover what he has been up to.

The patriarch of the Kohayagawa family of sake brewers leaves the running of his ailing business to his juniors, after a chance meeting with his former mistress. He regularly travels to Kyoto to see her and the daughter who might be his own. His three legitimate daughters back home, however, don't take too kindly to his schemes once they discover what he has been up to.

Often quite funny, thanks to Nakamura's spot-on performance as the old man who bends over backwards to keep his excursion a secret when the viewer knows his family is well aware of his intentions. This main storyline is contrasted with two of the Kohayagawa daughters' own search for a husband, the spectre of their father's infidelity hanging over them. Akira Takarada, best known abroad for fighting Godzilla, has a small part as the love interest of one of the daughters. [TM]