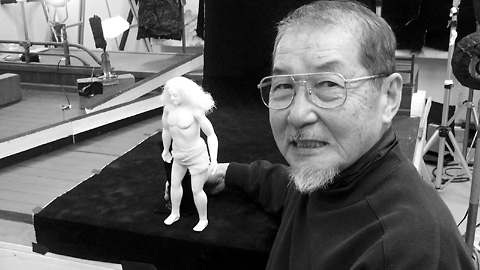

Kihachiro Kawamoto

- Published

- 29 November 2004

by Jasper Sharp

If Japanese animation is gaining an ever-increasing legion of overseas admirers, the work of those active outside of the nation's major studios still appears to be bewilderingly overlooked. One such character is Kihachiro Kawamoto, a pioneer in the neglected field of stop motion puppet animation/. Born in 1925, Kawamoto has been working in the medium since the 1950s, but it was not until a fortuitous meeting with the Czech maestro Jiri Trnka that his puppets truly began to take on a life of their own.

With his guiding hand behind the 2003 showcase of Japan's top animation talent, Winter Days (Fuyu no Hi) signalling a long-overdue return to the medium, Kawamoto has now embarked on his feature-length magnum opus, The Book of the Dead (Shisha no Sho).

Can you tell me about the project The Book of the Dead?

It's been a long-term dream of mine to realise this project. The main reason why I wanted to make this film is that the world is now confused and in panic, and there is war actually happening for no reason. I am trying to heal those innocent people who have died in recent wars. That is one of the main reasons I am making this movie. The theme is relieving these people's souls.

What attracted you to the story, the original source novel by Shinobu Orikuchi?

It's difficult to explain what happens in the story in a short time, but it is based on a true tale from the Nara Period, set around 750 AD. The story is set amongst the nobility, in the Nanke branch of the Fujiwara family, one of the four family branches descended from Fujiwara Kamatari (614-669). It is the era when Buddhism was being introduced from China, and the princess of this high-class family starts to wake up to this world.

This is only your second feature-length work, after Rennyo and His Mother (Rennyo to Sono Haha) in 1981. Why are you making The Book of the Dead now?

As I mentioned at the beginning, I wanted to express my wishes about relieving those dead people's souls from chaos using the original Japanese Buddhist teachings of relieving suffering. This original Japanese Buddhist concept is different from the Yasukuni shrine's idea. No matter who it is, either an enemy or a friend, the souls of the people who have been killed need to be relieved. That is the Japanese original teaching that came from Buddhism. I am showing this concept from the original teachings through the main character in The Book of the Dead - the princess of the Fujiwara family.

I haven't had the chance to make this film before. I've never had the money. But I was encouraged to work on this film by the producer, Junko Fukuma of the Sakura Motion Picture Company, because it is a story I am very passionate about. This is fairly common in the industry. Even a director like Akira Kurosawa had a lot of projects he wanted to make but couldn't get the funding for. But now seems a better time than ever to work on this project, so I seized the chance.

How did you first become interested in puppet making?

It's been my hobby since I was a child, even before I went to elementary school. But actually the first time I really ever understood what a puppet was, I was already over 40 years old. This was when I went to Czechoslovakia and met Jiri Trnka, who taught me a lot. He opened my eyes and only then did I begin to understand everything there was about the puppet world.

What distinction do you make between puppets and dolls?

Dolls are children's toys, or things you dress up and display. Puppets, or marionettes, are things that act. This is a crucial difference. There's no such thing as doll animation.

When I started, I was making dolls. I started making puppets at around the age of 25. At this age I met Tadasu Iizawa, and we formed a group making puppet storybooks, illustrated books featuring puppets. Even though these were really dolls, I call them puppets because they were actors within the books. During that time I was working with Tadasu Iizawa, I first saw the work of the puppet animator Jiri Trnka, and that was a major influence.

Were you influenced by the stop motion animations of Russian Ladislaw Starewicz?

Yes, I know of him. This was a Russian émigré who moved to Paris. I saw his movies in Japan. Perhaps he was the founder of puppet animation.

When did you start making stop motion animation yourself?

I started in 1953. That year, television had just begun and was spreading across Japan. During World War 2, an animator called Tadahito Mochinaga had been in China, in Shanghai, making both cell and puppet animations. He was the first Japanese person to make stop motion animations. After the war, he came back to Japan, and it was he who trained me. In 1953, I made a 2-minute TV commercial using stop motion puppetry.

In 1958, you founded Shiba Productions with Tadasu Iizawa. What kind of works did you make?

These were commercial animations for TV.

I read that you worked for Toho between 1946 and 1950, during the time of the famous workers strikes at the studios.

I worked as an assistant art designer at the studio. At the time, just after the war, the Japanese economy, and politics and society in general, was in total chaos and Japan was wondering which way it should go, left or right. So it was a very interesting time to be working in an environment like this, because artists and filmmakers have a lot of passion to make great works, while the company itself was primarily interested in making a lot of money.

So that was why there were always struggles between the workers and the management at the company, which is when the strikes occurred. At the time, there were a lot of great veteran filmmakers at the studio - Teinosuke Kinugasa, Shiro Toyoda, and Mikio Naruse. Akira Kurosawa was young back then, but he was also there. So there was a good atmosphere at the studio, and a lot of great people making great movies.

So I learned a lot about making movies during this period of time, such as how movies are made, how sets are constructed and a lot of technical aspects. The main difference between a regular animator and myself is that I started from this film background. Toho was a great school for me.

Your animation work seems more influenced by work from Europe, particularly Eastern Europe and Russia, rather than American animation. What do you see as the difference between the two styles?

I don't think I am so influenced by the European style so much. I had watched a lot of American animation such as Disney's films since I was elementary school age, but I don't think it made me want to become an animator. I only started thinking about making animation after seeing Jiri Trnka's work. The reason why I was so into Trnka's animation was that he was able to tell a story in a poetic style through the use of puppets.

How did you eventually come into contact with him?

I contacted him directly. I sent him a letter and waited for over 6 months, and then finally this lovely reply came from him. I couldn't write such a nice letter as this even now. He wrote that puppets are the one thing that transcend nationality, race, and religion. So he wrote that it would be his pleasure to welcome me to Czechoslovakia to study puppet animation under him.

So in 1963 you studied in Prague under Trnka. How easy was it for a Japanese person to enter Prague during this time?

It was really difficult. The Tokyo Olympics were held in 1964, and this was really the first time Japanese people found it easier to go abroad. Even getting a passport at this time was a tough thing to do. So I got a passport by saying that I was a writer for a newspaper publisher and I was able to get a visa fairly easily because of the letter from Trnka.

How did you communicate with him?

It was really difficult to communicate with Trnka. He was like a god figure for me, so it was difficult to talk to him naturally. More than this, Trnka didn't come to the studio all the time. For the first month I didn't even see him at all. I was a little worried.

The first time I went to the studio when Trnka was there, he introduced me to all the staff and the studio system, but after that I didn't see him for another month or so. From that time I was able to keep going to the studio and communicate with the other studio workers. I wasn't really working. I was watching and learning and picking up the skills from the other workers at the studio. I was also learning Czech at the time, so after around six months I was able to understand a little bit.

What was it like living in Prague at the time?

It was totally different from Japan. For example, in the evening it wasn't lit up like Ginza in Tokyo, so it was really dark and people had to come right up to your face to see who you were. That year it was a really bad winter all over Europe. The wind was really strong and the electricity situation was bad, it was always dark outside. There were hardly any vegetables, nor much else to eat. So living there was pretty tough. The reason why I was able to survive was because the people were so great, especially the people working in the studio. I've never forgotten the kindness they showed me. I don't think you see this sort of kindness anywhere any more.

I was around 38 years old at the time and I didn't even have any of my own works with me, but they still treated me so well. Even the people like the studio helpers. After six months or so working there, the old woman who came to the studios every week, creating the costumes for one of the movies, asked me if I was from Vietnam, because at the time the Vietnam War was going on. That was a really good period of time in my life. Maybe the best.

During the 1960s, animation was becoming a very big business in Japan. How easy was it to get your early works such as your first film Breaking of Branches is Forbidden (Hanaori, 1968) made and shown?

It wasn't easy at all. I worked about a year to get enough money together to make Breaking of Branches is Forbidden. I was working horrible jobs, for example making animated commercials. I went back to Shiba Productions, which I'd already left once to make my own puppet animations, so it was really difficult to return to this kind of work again. This was the worst year ever of my life!

We rented a hall to show the film after it was made, and got the audiences to come and watch it. Usually all of my films were screened like that. It was very rare that companies bought my films for distribution in normal theatres.

Was this a common thing for animators at the time?

Even nowadays this is the case. For example, recently Koji Yamamura with Mt. Head raised the budget himself to make the film. The situation hasn't really changed in 40 years.

What was Echo Productions?

This was the company of my fellow animator Tadanari Okamoto. During that time television still wasn't so widespread, but there was a distribution system for educational films, where the films would be shown in schools all over country. So they would rent the prints to the schools and this was enough to cover the costs of production. There were so many animators working around that time, but Okamoto was the only one who really managed to find himself in such a comfortable financial situation.

Okamoto knew this distribution route really well, this system of supply and demand and all the people who worked within this system. At the same time, he managed to find a nice balance between making the kind of artistic works he wanted within these constraints.

So for six years we worked together booking private halls to show our films. In my case, I made the kind of works I wanted to make. I didn't really care if it was commercially successful or not. As long as the work was great, I was satisfied with it. That means I had to make the money elsewhere, and in this way TV helped me a lot in getting the finances together. I was working regularly on an educational TV series for children making live action puppet animations. During the time I made my finest animations, such as Doujouji Temple (1976), I had a lot of money coming in from the merchandising from the puppet characters I had made for these TV programs. They appeared on cups or on clothing for example.

Between Demon (Oni, 1972) and Doujouji Temple (1976), you moved away from puppet animation to cut-out animation. Why?

Puppets make their own story, while with cut out animation the story is created by the animator. With films like A Poet's Life (1974) I didn't think the story was well-suited to puppet animation. I'm not actually a cut out animator myself and I think the work is not so good. So after A Poet's Life, I decided not to do this anymore.

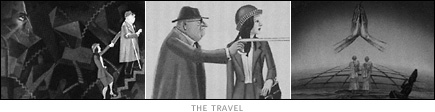

I think the cut out animation Travel (Tabi, 1973) is a beautiful, dreamlike work. But what does it mean?

A lot of people say "I don't get it", but I know very much what it means. In the Spring of 1968 the Soviet Union invaded Prague and killed a lot of Czech people. The film is about the Life of Suffering.

Buddha says that life is suffering and there are four basic sufferings: birth, disease, aging, and dying. These are the four major sufferings in a person's life. There are a further four sufferings that Buddha spoke about. These are having to meet people you find annoying, being parted from a loved one, not getting the things you desire, and the sufferings of the mind and body. In order to get rid of those sufferings one must achieve a state of "satori", or enlightenment. This is the theme of Travel.

All of these elements of the eight sufferings are contained within that movie. The main character of the girl wonders if the Indian man she meets might be her lover from a former life. There's a scene where she drops the statue she is holding.

The Book of the Dead is basically about these very same themes.