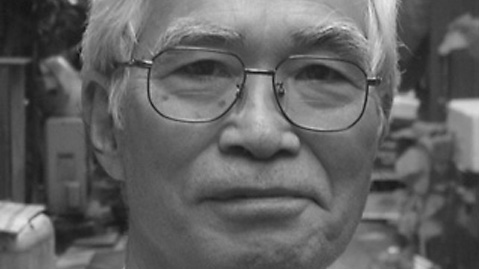

Masao Adachi

- Published

- 21 August 2007

by Jasper Sharp

The year 2007 sees the long-awaited return to our screens of Masao Adachi, one of the most challenging, thought-provoking and controversial figures ever to emerge from the world of Japanese cinema. His new film Prisoner/Terrorist is his first feature in over thirty years.

Born in 1939 in Kita Kyushu, Adachi emerged from the Nihon University Film Study Club, better known as Nichidai Eiken, alongside filmmakers like Motoharu Jonouchi and Isao Okishima, to become one of the leading figures in the underground experimental scene of the 60s, with films like Sain (1963) and Galaxy (1967). However, it is for his later associations with Nagisa Oshima, in whose Death by Hanging (1968) he appears in the role of the security officer, and more famously with Koji Wakamatsu, scripting dozens of his most famous titles including The Embryo Hunts in Secret, Go Go Second Time Virgin, Sex Jack, and Ecstasy of Angels, that he is best known.

Through Wakamatsu Productions, Adachi also contributed the pink genre's most energetic and revolutionary titles, films such as Sex Play and High School Guerrilla. He furthermore became known as one of the country's most progressive film theorists and critics due to his instrumental involvement with the journal Eiga Hihyo during its second phase from 1969 to 1973.

And then he disappeared from Japan, apparently disillusioned with the direction along which the country's commercial cinema was heading, leaving for Beirut where in 1974 he joined the Japanese Red Army in lending its assistance to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and their quest to fight for the liberation of the Israeli-occupied territories. He was not to return until 2000, after his associations with the JRA saw him extradited from Lebanon to face a brief jail sentence back in his home country.

Adachi's reappearance after three decades saw the name of this agent provocateur firmly back on the lips of local cinephiles, with retrospectives and DVD releases of his earlier work followed by the publication in 2003 of Eiga / Kakumei, a collection of interviews conducted by Go Hirasawa. Prisoner/Terrorist is his first film since his return.

Midnight Eye would like to express thanks to Go Hirasawa for his invaluable help in coordinating this interview, which was conducted by email.

Prisoner/Terrorist is a film about Japanese Red Army member Kozo Okamoto. Can you tell me why you chose this subject for your first film in over three decades?

The reason I chose this particular theme for my cinematic work Prisoner/Terrorist is that I wanted to look back upon my experiences from the last 35 years, and from there to sum up my own theoretical ideas and the experiences gained from my other activities, both relating to the revolution and other matters.

What do you mean by the word 'revolution'?

I'm using the word 'revolution' in its most general sense, talking not only about revolutionary movements in the field of politics, but also in the arts and other socio-economic areas. My idea is that the world is moving on a daily basis and is in a transitional period towards a final revolution of mankind on every level. My use of the word is not limited to any one specific meaning.

I am interested about how much is generally known about the Japanese Red Army and the 1972 Lod Airport Massacre in Japan at present. What was the reaction among the critics, for example, and also the viewers who watched the film? Were they generally familiar with the back story? What kind of audiences did the film attract?

Because of the recent situation in the Middle East, with regards to Palestine in particular, the Japanese mass media have begun to write about it, especially in the early stages of the so-called "War on Terror" campaign that has been engineered because of 9/11. Because of this the Japanese public has had its memory refreshed about the Japanese Red Army and the Lydda Airport Operation.

So far the opinions from the film critics have been generally good and friendly, and I've got to hear many different opinions about how differently the film is constructed and how fresh it is in its approach.

Because the general public who came to see the film knew this back-story, I can also add that some of them were quite critical about the film. Firstly, they felt disappointed or let down because there is not enough political explanation or summary of the activities of the New Leftist movement in 1970s, but also, they criticised it as being too much of an idealistic explanation.

Anyway, I'm not entirely sure, because I haven't been able to keep close track of audience reactions to it entirely by myself, but I heard that the viewers were equally divided between young and old, and for the most part understood the background history pretty well.

Though the film is clearly about Okamoto, the protagonist played by Tomorowo Taguchi is never referred to by any name except 'M'. There are also other characters obviously modelled on real-life figures like the JRA founder Fusako Shigenobu, but who remain anonymous within the film. Why do you never draw a connection between these characters and their real-life counterparts?

All the time in my filmmaking I have depicted people who come entirely from my imagination - or I could say, that through my images I have always tried to explore characters who exist only within film.

In the case of Prisoner/Terrorist, through using a real historical event as its basis and existing real-life people such as Kozo Okamoto, as well as other historical revolutionaries and philosophers, I tried to create a unique story and characters. So, as far as possible, I did attempt to divorce the film from the reality of the historical event and the real characters of all those involved. All the actors and actresses were asked to create their own interpretations of their characters, and not to copy the real existing figures.

Is it possible for you to tell me a little bit about your own personal relationship with Okamoto? For example, where you met him, your impressions of him as a person?

Prior to his departure to the Middle East [before 1972 - JS], I had met him once or twice, just in passing. Our comradeship really began in 1985, just after the time when he was released from Israeli imprisonment through the arrangement of the International Red Cross in exchange for POWs and he rejoined to the Japanese Red Army. In 1997, after the time when we were arrested together along with 3 of our other comrades, for 3 years we were obliged to share our life together within a small prison cell. And then in 2000, he was granted political asylum in Lebanon while the 4 members of the JRA, including myself, were forcibly sent back to Japan.

Did Okamoto have his own strong political belief system, or was he swept away with the spirit of the times, do you think?

Kozo Okamoto, one might say, was one of the typical student activists of the "Zenkyoto" student movement in Japan at that time. He was the chairman of the student committee at Kagoshima University and studied a little about Marxist-Leninist philosophy, but he was not a dogmatic ideologist; he was more a naïve activist not belonging to any party or political organization.

In addition, he had rather a special background. He had incredible respect for his elder brother who went to the Democratic People's Republic of Korea after hijacking the JAL plane, and he tried to follow his brother as a revolutionary and was determined to go to the Middle East and become an international volunteer for the Palestinian national liberation struggle. [His brother was Takeshi Okamoto, one of those involved in the famous Yodo hijacking of 1970, Japan's first-ever plane hijacking. Several of the 'Yodo Five' hijackers can be seen in Yutaka Tsuchiya's documentary The New God - JS].

Those who are not familiar with your films and only know your personal history might think of you as the ultimate "guerrilla filmmaker" - a director who made revolutionary propaganda and then headed off to the Middle East to join the world revolution. In this context, it is easy for those not familiar with your work to misinterpret Prisoner as being anti-Israeli or anti-American. However, when one looks at a film like Sex Play, it seems clear to me that you are not putting forward your own world view or pushing your own personal politics, but you are looking at how people become associated with various extreme political movements or positions, what revolutionary action means to them as individuals and how it fuels their life. There's always this interesting rupture between the characters' actions and their beliefs. So I see Prisoner as very much an attempt to get inside the mind of someone who has been pushed into a very extreme action due to their own strict adherence to a certain ideological doctrine, and then has to spend the rest of their life rationalizing or justifying their actions to themselves. Was this the intention?

What I can say for myself is that although I am anti-Zionist and against US international policy, I have never tried to make any anti-American films. In the case of Prisoner/Terrorist, some people who expected to see an anti-American or an anti-Israeli film felt rather let down, because I haven't tried to talk on this level of politicized ideas.

In contrast, I have tried to talk about the notion of freedom for a human being by drawing parallels between terrorist activity and state terrorism (including prison itself, security intelligence, the prison guard system, and so on). In this film, I can honestly say, I most concentrated on the theme of what happens to the personal inner world of a person - the world of individual belief, confidence, and thought - by expressing the discrepant lag of space/time in relation to the outer/inner sense of temporality of so-called terrorist life, of time under torture and incarceration, and the temporality of real society, that is, in the real world outside of a prison.

And I also tried to portray how a person who had had no confidence or belief in his own activities could start to deny all dogma and then create his own justification for both his revolutionary ideals and the actions of his own life, through his experiences within this space/time of prison existence.

So the most important aim for me was not to offer any justification for his sense of confidence in himself, in his beliefs or his actions. It was not to offer excuses or atonement for him on any level, but to try and seek out the meaning of individual freedom through his experiences.

I'm talking on a more existentialist level, where ideas such as "self-sacrifice" and "self-criticism" really mean nothing. Using the character of 'M' I have tried to explain the meaningless of self-justification or dogma for an individual on any level.

When one looks at your filmography, one can see a progression from the very abstract early experimental films like Wan (1961), followed by the cryptic political allegory of Sain (1963), then the more detached, analytical, and often playful look at revolutionary movements in your pink films for Wakamatsu Pro, like your own Sex Game and High School Guerrilla (1969), then your scripts for Wakamatsu's Sex Jack and Ecstasy of Angels - which really seemed to reflect what was happening on the streets at the time. And then finally there's the more overtly political films like AKA Serial Killer (1969/75) culminating in your most didactic work, The Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War (1971). With over 30 years now since your last film, I was wondering where you would position Prisoner within this evolution?

Thank you for your analytical evaluation of my cinematic works. And if I can answer your question regarding the position of Prisoner/Terrorist in my career, I believe it is quite far removed from the tendencies and inclinations of my other films, and the culmination of my cinematic work so far. At the same time, I could also say it is closest to Sain and Embryo Hunts in Secret, because I'm trying to explain the inner worlds of my characters by using the discrepant lag of the space/time.

The one area I felt slightly uneasy about with the film is that it rather glossed over Okamoto's role in the Lod Airport Massacre and concentrated a lot more on his ill-treatment while in prison in Israel. How would you accept this criticism?

If you were expecting to see the real story of Kozo Okamoto, then I apologise. But as I already explained, rather than to talk about the real figure of Kozo himself, my theme in this film was to explore the process of an individual finding his meaning in life through him initially undertaking his suicide operation, and then struggling to regain this meaning after that, after failing in his suicide attempt and surviving his tortures within prison.

So I believe that in many instances he is confronted with the direct results of his original terrorist attack, such as in his discussions with the religious officer. Anyway, within these ideas, I am not concerned with, or rather, I haven't considered this balance or mutual correlation between murderous terrorist activity and suffering under torture.

The book of interviews with you conducted by Go Hirasawa which was published in 2003 was called Eiga / Kakumei, or 'Film / Revolution'. Is filmmaking an act of revolution for you? What is the relationship for you between your own cinematic works, your personal politics and belief systems about the world, your own ideology, your own actions, and the process of bringing your thoughts to the screen? It seems to me that you are very much exploring this relationship within your films and through the process of filmmaking itself.

For me personally, there is no conflict between my cinematic work and activities within the revolution. Again, when I talk of revolution, I've come to understand through my own experiences that while there is no strict division, there are many differences between revolution and reformism on the way towards the final stage of this revolution.

On the contrary, generally I think of my work in the field of cinema as a process of revolutionizing myself, and in this way my cinema will stand independently in relation the activities of the revolution.

So, throughout the entire filmmaking process of bringing an idea to the screen, I am trying to confront the problems of recent current events and situations, and to sum up my own political beliefs and theoretical convictions, and also to look back to my own activities in the past. The meaning Eiga / Kakumei is that everything is related to my cinema work, and nothing is cut off from it, but that all of these relationships are embodied in my cinematic images.

In recent years there have been a number of films looking at the final implosion of the New Left movement in Japan, and particularly the 1972 Asama Sanso incident. For example, Kazuyoshi Kumakiri's Kichiku (1997), Banmei Takahashi's Rain of Light (2001), Masato Harada's The Choice of Hercules (2002), and now your old friend and collaborator Koji Wakamatsu is making United Red Army, due for release next year. Why do you think this period is so fascinating for filmmakers and audiences now?

It seems this is not only a tendency in Japanese cinema. It is happening simultaneously on an international level. Many film works are now looking at summarising the politico-theoretical ideas of the New Left movement of the 1960s and 70s. At the heart of this issue, there is a common sense of understanding between many cinematic artists about exploring new ways of resisting globalisation, which is aggressively asserting capitalistic control not only towards individual societies, but also trying to impose a standard level across the world.

As this suggests, on an international level, people have begun to look back at these sensitive lessons - the legacy of the New Left movement's revolution for personal freedom in the 1960s and 70s and the reasons why the movement became widely mobilised but ultimately easily failed to create a revolution - and now during this decade they are looking at what is happening in relation to the activities of people working in many different fields of art, culture, and political mass movements

So this is my opinion why many filmmakers of all political persuasions and positions are looking back to the "war" of the 60s-70s. The cinema works of Japan also are trying to encapsulate or sum up the "war" of that era. I don't just mean the "Tokyo-Osaka War" of the new leftist movement in Japan [the period of student protest and civil unrest during the 60s is often referred to in this way in Japan - JS], but also the many different levels of struggles for national liberation all across the world.

The Japanese title 'Prisoner' (Yuheisha) also has the furigana subtitle Terrorist in katakana, (Terorisuto). I notice that the English language publicity material avoids using this word "terrorist", which has become very emotive in countries like America and Britain after 9/11. Was this your choice?

The original title that I chose was Prisoner / Terrorist (Yuheisha / Terorisuto). It's a pity if it has been changed to just Prisoner, and I'm disappointed. Usually, I try to make use and explore the meaning of these words "terrorism" or "terrorist", because after 9/11, the "War on Terror" campaign initiated by the USA and UK spread all over the world, and one of the original implied meanings that I understand behind the word terrorism, of meaning "against the ruling power" or "anti-authority" has become corrupted. In the film I refer to the original derivations of the word as it was first used during the Reign of Terror (régime de la terreur) during the French Revolution, and also later by Russian revolutionaries. Even though it might be provocative, the title should be Prisoner / Terrorist, as the intention behind my use of the word is to draw attention to the conspiracy behind the "War on Terror" campaign initiated by the governments of the USA and UK.

Did you have any difficulties finding places to screen Prisoner in Japan?

There was nothing special. The only problem I can really talk of is that theatres are dominated by Hollywood action cinema, and so we have fewer theatres left for screening Japan's own productions.

In which other countries has the film been shown so far, and have you had any feedback about how it was received?

Up till now, it has only been screened at film festivals, and not had a general release overseas. It was invited and screened at festivals in Germany and Korea [at Nippon Connection and Jeonju; it has also been screened at the Japan Society in New York, and will be screened at Raindance in London in Sept/Oct - JS]. I only heard about these screenings, but apparently the film got a large audience. So I believe in the near future it will get a reaction.

This is your first film in over 35 years, and so of course your first-ever attempt using digital video. How did this new technology influence the process of filmmaking for you?

For a long time before I made this film, I'd decided that if I was to start again as a film director, I would use digital video. Because I thought that by using a high-tech medium, I would be able to find a freer method that best fits the expressive style of my cinema.

However, I also understood the practical considerations behind using it were slightly different, because the digital video system is still tied to the conventions of commercial film production, and hasn't freed itself from this system to evolve along its own line yet. By this I mean that the post-production studios all use the same type of computer systems designed to produce films along the picture/sound model of commercial mainstream cinema, which makes it difficult to adapt to my style.

For example, in my film, I tried to design the entire soundtrack without differentiating between background noise, music, and dialogue/monologue, and I also never held back from only using these background noises as part of the film. This is in contrast with the conventional style of filmmaking, and the engineers at the studio couldn't come around to my way of working. They just said "noise is noise, and it's going to be impossible to show it theatrically, because the projectionists and the engineer at all the theatres, and the audience too, will just think that there's been mistakes in the sound engineering."

In my following works, I want to try and investigate the possibilities of this new digital medium further and push it towards a more experimental style.

Many of your best known films were made with Wakamatsu and were shown in pink film theatres in the sixties. Do you ever feel tempted to go back and make a film for the seijin eiga (adult film) audience again?

I hoped to make a new seijin eiga to experiment with some new styles of film expression, but the producers in the pink film field said to me that due to the poor budgets and rapid shooting schedules, my style of cinema is not particularly suited to today's pink filmmaking scene.

From my own experiences trying to get interesting films shown to wider audiences, I know that one of the largest problems today in the UK is that there simply aren't enough screens to keep up with the large number of new films and filmmakers coming out all over the world. I find this an insane situation, because theoretically there are more "screens" than ever before, in terms of the amount of TV channels available to us, internet Video on Demand services, mobile phones, etc - we spend our lives looking at screens. And in this digital age, it is far cheaper to distribute films globally. In general this is a very exciting time in cinema across the world, and yet if you go to local cinemas or look at what is showing on television, it is very difficult to detect this. Smaller, more interesting films (and in Britain, subtitled films and especially subtitled documentaries) are becoming more marginalised and increasingly difficult to see. The multiplexes all seem to be showing the same old standard entertainment films, and even the so-called 'independent' art house circuit here can hardly be described as independent any more. How does this situation compare with Japan today, and how different is this from when you were active as a filmmaker?

In the present climate of filmmaking, as you say, the methods and means of cinema expression have become more and more widely developed and fresher. But the film industry itself, as much as other industries like the TV, book, music industry, etc, has become much harder in its approach, more controlled by the monopolist market system and, in comparison with the field of cinema 40 years ago, much more narrow in its focus.

Following on from this, I am wondering what you think the situation is for new filmmakers whose work or ideas challenge the establishment. Is there still the possibility for new filmmaking movements today as for example happened in Japan in the 1960s, with for example Shinsuke Ogawa's documentary-making collective Ogawa Pro, or, of course, Wakamatsu Pro?

In spite of the more limited possibilities for film screenings, if you opt to go outside of film theatres, in reality there are actually many other kinds of opportunities for making challenging new cinematic works nowadays. Using new high-tech methods and systems, I believe, we can work more and more to show our works freely to people all across the world, just as successfully as underground cinema and theatre have continued to do. I'm planning to initiate some kind of fresh style film projects in this direction in the near future.

Can you elaborate on any of these?

At the moment, I'm trying to continue with a kind of 'diary' style of cinema. I'll be the director/cameraman for this project, and at the same time, some musicians will start making noises while I am filming. So it'll be a kind of free jazz session style, but in the form of cinema.

One reason why I am interested in this issue is that films such as Ecstasy of Angels and Red Army - PFLP Declaration of World War were stopped from screening due to police pressure, and so with the second of these films you actively toured around the country taking it to audiences, in a slightly similar manner to Shinsuke Ogawa creating his own distribution system for his documentaries. I can't think of any cases of the police stopping films from screening now, but I wonder if the situation is better for more radical filmmakers at the moment?

I think that today's ruling powers are thinking they can develop a way of controlling all the various different kinds of media and information systems by way of the law, so almost every form of media (not just cinema but those such as TV journalism, radio, and newspapers too) falls under the authorities' control both directly and indirectly. Furthermore, the media themselves have their own strange characteristics regarding self-regulation and self-censorship that comply with the wishes of the ruling authority.

So I believe that even the situation for filmmakers has gotten worse. If you can work without any system of regulation or control, then you can increasingly utilise and develop a fresh mode of cinema.

During your time in the Middle East, I know you were shooting a lot of 8mm footage, as a kind of visual diary. What were you intending to do with this footage, and does any of it still exist today?

In 1974 after the campaign of screening of Red Army-PFLP Declaration of World War, I started to plan the next documentary film "NO.2". For this reason, I went again to the Middle East and started filming the Palestinians' life in the refugee camps and military camps. But unfortunately, all of my film archives in some stock places were destroyed by the air attacks of Israeli military fighter-bombers in 1982 and other years. There is some possibility of searching parts of the archives, but again unfortunately, I'm rather like the main character in Prisoner / Terrorist in that I myself can't leave Japan, so there's no possibility to look for them.

Can you explain in your own words, what was fukei-ron, or Landscape Theory, which you developed along with Mamoru Sasaki and Masao Matsuda at the end of the 1960s?

It's a very simple matter. All the landscapes which one faces in one's daily life, even those such as the beautiful sites shown on a postcard, are essentially related to the figure of a ruling power. This was the starting point for our discussions on the Theory of Landscape.

Koji Wakamatsu's recent film Cycling Chronicles: Landscapes the Boy Saw has a scriptwriting credit for Deguchi Deru, a pseudonym used by you (and many other people it's true, but mainly by you) during your time at Wakamatsu Pro in the late 1960s. The title also alludes to Landscape Theory. What exactly was your involvement with this film?

The director Wakamatsu had been planning this film for a long time. During the film's preparation, I was involved in writing some form of script, but later, my ideas became unsuited for his goal with this film. So all I can say is that I wasn't particularly closely involved with this film.

Any final words?

Thanks for your work as cinema critics and coordinators for all the cineastes.

Good luck!