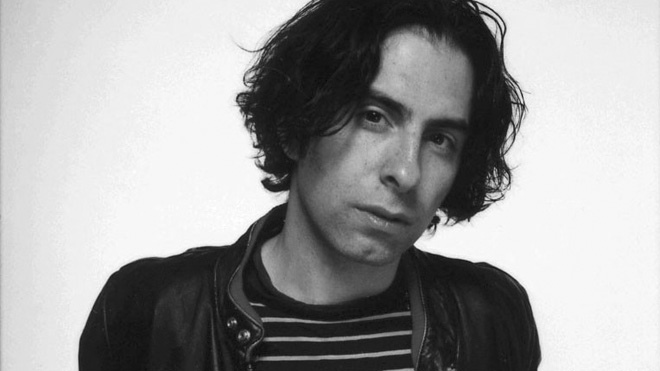

Michael Arias

- Published

- 23 April 2009

by Tom Mes

After years of working in visual effects and the animation industry, Michael Arias made his name as a director with Tekkon Kinkreet, a.k.a. Black and White. Adapted from Taiyo Matsumoto's cult manga, the film was screened at the Berlinale and found an eager audience around the world. Arias's new film Heaven's Door may come as a surprise to those who have been following his various forays into anime (alongside Hayao Miyazaki and on The Animatrix, to name but two of his numerous credits): his sophomore effort sees Arias moving into directing live action.

You've just directed your first live-action film, Heaven's Door. How did this land in your lap?

I'd been looking for a while to direct a live-action feature. I was developing something on my own when a producer at Asmik Ace named Mitsuru Uda came to me with a project he was trying to put together with Fuji TV, a remake of the German film Knocking on Heaven's Door. They thought that it might be something for me. The original film is a kind of action-comedy road movie and I didn't really see what made them come to me for it. But they said I could completely rewrite it. I wasn't crazy about the first draft of the script they had, so I agreed on the condition that they give me six months to work with the scriptwriter. In the end there wasn't much that resembled the original. The original film is about two guys who meet in a hospital, both having just found out they only have a very short time left to live. One of them has never seen the ocean and the other one makes it his mission to show him the ocean before the end. So they bust loose from the hospital and go on a road trip.

What did you change?

In the original they don't pay much attention to the places they go through. It's a kind of madcap car chase. I thought if we could do something interesting with the two main characters and also focus a little more on their actual surroundings, that that would improve it a lot. I wanted to do something where you could really feel them move from an urban or industrial, man-made environment to a very natural place where there are almost no people and no machines. Almost like going back in time, toward something more primitive. Surreal but already halfway to the other side. I thought that would be interesting, because I really like the Japanese countryside. I wanted to do something where you could have fun with all that rusted corrugated aluminum, the old signage, all the ramshackle scenery that you can find even just outside Tokyo. A lot of Tekkon was based on that kind of imagery and I never get tired of it.

Where did you find the locations?

Most of it's not too far from Tokyo, also because it would become too expensive to ship and put up the entire cast and crew in faraway locations. We shot in Chiba, Ibaraki, a lot in Shizuoka. We spent about four months scouting locations and we found some really rundown towns. The streets would be newly paved, but some of the buildings were just left to rot. Most of it will be torn down before long.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa says he likes shooting those decrepit buildings as a way to leave a record of their existence.

Yeah, that's kind of the idea. Most of what we use in the film won't be there anymore next year. There are still people living and working there, though. The whole movie basically takes place outdoors and we have to show quite a progression of locations. We needed to find as much variety as possible, while keeping within half a day's drive from Tokyo. You have all these holes that you have to fill, and you basically have to use stuff that exists, since we don't have a budget to build sets. At the same time I want to do something that's visually unique, which is more of a challenge than I expected. There's a lot of places that look amazing, but you can't get permission to use them. That can be annoying, but then again, I'd never let a film crew use my house either.

Who was your art director?

Namiko Iwaki, she art-directed Sakuran and also Josee, the Tiger and the Fish. Sakuran was all sets of course, and Heaven's Door was mostly locations, so sometimes she felt that her hands were tied. There were times, like the scene in the chestnut orchard, where there was absolutely nothing for her and her team to do. But I'd like to try working on something that is a bit more designed, maybe something that falls in between animation and live action in terms of the art direction, something that's more set-bound.

You spent quite a long time editing the film.

We shot the film early 2008, and we finished post-production the first week of August. I wanted to get my hands dirty without spending a lot of money. The most costly part of the production is the actual shooting, when there are a lot of people and a lot of equipment involved. I asked my producer to give me as much time as possible in pre-production and post-production. Pre-production is fairly easy because most of it is just me and the screenwriter. Post is a little more involved, because it's me, the editor, the sound designer, and then the musicians. But still, less so than the actual shooting. Also, post is the part of filmmaking that I have the most experience with. It's something that's not so different from animation or anything I've done before. I felt that that was one area where I could make my influence felt more easily, and it's something that I enjoy doing, I like editing.

I think a lot of Japanese directors who make three films a year tend to hand off the editing and post. They will already be involved in the next project while the last project is still being finished. They will come in and give notes and such, but it seems the directors on medium-budget films are more likely to delegate a lot of the post-production work. But I had such a good experience supervising the post on Animatrix and working very closely on post-production on Tekkon, so I wanted to be really involved in post for Heaven's Door.

But the line between production and post-production is not as clear in animation as it is in live action.

Post-production on an animated movie really happens while the movie is still being made, so it's not a discreet process. You're editing and doing sound and doing music while you still have shots that aren't finished. It's not like with live action, where you finish the shoot and then you hand all the elements off. In animation it all kind of builds toward a very sharp point, but in essence everything is being worked on in parallel. Each shot is its own pipeline, which is very different from live action where you gather all your bits together and you hand them off. That's when the crew disbands and another team of people, the editor and the post-production supervisor and all those people, come in. I wanted to have as strong a voice as possible in post-production. As it worked out, the editor and I would show up every day and sometimes I would cut scenes, sometimes she would cut scenes, and sometimes we would re-cut each other's scenes. She wasn't cutting and showing me finished stuff so much as we cut the whole movie together.

Who was your editor?

Mutsumi Takemiya. She was my editor on Tekkon and she comes from an animation background. She has a very interesting way of working, more open to trying something different and a little less bound by the traditions of live action editing. A little more likely to put a different spin on things than somebody who worked for a long time cutting live action. She was a little overwhelmed at first by the amount of footage that we had, because in animation at most you have exactly what you storyboarded. It's a subtractive process after that, where you can take a couple of frames out here or there. You can cut the mouth off a character in one part of the scene and place it on the same character in another part of the scene, or stretch out the space between lines of dialogue. Of course you can change the order of the scenes, but there is no real way in animation to make drastic additions to what you've got. Whereas in live action, if you're shooting the way we were, with three or four cameras rolling at the same time, you can build the movie up and cut it back, and then build up certain parts to emphasise one section or another. It seemed a very different process than with animation.

More like a puzzle.

Yeah, I think so. In animation it's more like a model train set. You put everything together and then you make nips and tucks to get everything to fit better. I really enjoyed editing on Heaven's Door. I spent more time on it than maybe a veteran editor would have, but a lot of the things I like about the movie came together in editing.

Was it your intention from the beginning to shoot with multiple cameras?

Yes. I wanted to shoot the movie in long takes with at least two cameras and use a lot of steadicam. That was something I discussed with my director of photography the first time we met. He was very open to that and he has a really good relationship with one of the best steadicam operators in Japan so we were able to get him on the shoot with us all the time and bring out the steadicam anytime we wanted. If we didn't use steadicam he would usually handle the B camera. My DP and I would pick the main camera position and then the DP would delegate alternate positions. Sometimes it was basically the same shot but at a tighter angle, sometimes it was a completely alternate look at things. It worked very well, we ended up with a lot of footage despite the short schedule we had, just because of the extra angles. We ended up with about 50 hours of footage, though about six or seven hours of that was driving stuff. Every time we changed locations we would put a camera staring out the front window and one out the side window and we would just let it roll. We were shooting hi-def, we could just let things roll for hours at a time. We would drive for example from Ibaraki to Tokyo and just shoot whatever we found, and some of that stuff was really good and ended up in the movie. It's a road movie, so a lot of it is about having the sense of moving toward some specified goal. Ideally the locations mirror the development of the characters, and in our case it was important to have a move from a man-made environment to a more natural environment.

How about guerrilla shooting?

There was really only one moment where we shot without permission, which is the scene on Takeshita-dori in Harajuku. It's a really tricky area, you can't get permission to shoot there and if anyone complains about you, the police will show up. It's not like in New York or Los Angeles, where there is a film commission that can get you into any area. In most areas of Tokyo shooting in the street is a kind of grey zone, especially in that area of Harajuku, because there are a lot of store owners and basically anyone can say that you're interfering with business. So we actually had a production assistant who was designated the director just in case the police showed up. The idea was that everyone would split and leave this PA to take the wrap (laughs). It didn't come down to that and in fact it went quite smoothly. It was very exciting, we had a lot steadicam and a lot of gear in different positions. We'd negotiated with a few specific shops to allow us to set up a camera on their stairwell or something like that. But for the main walk down the street that Tomoya Nagase and Mayuko Fukuda take, we had about a hundred extras that we placed in such a way that they would form a barrier between the real crowd and the actors. We kind of hid in an alley, but of course once you're out there, there is no way to control the situation. You will get people noticing that Tomoya Nagase is walking down the street. We only did three takes of that walk, but each time we had to wait for about an hour between takes to let the buzz die down.

And outside Tokyo?

Out in the countryside it's a lot easier. Sometimes an entire town may be under one person's jurisdiction and then it becomes a matter of whether they like you and think your production is going to be good for their neighbourhood, or maybe they like movies or something. It's very informal, in the way that a lot of systems in Japan seem to be informal. You can do a lot of business on a handshake. We got a lot of cooperation from people.

You seem to be very much geared toward the collaborative experience of filmmaking. You're not the guy who says he's the boss that everybody has to listen to.

Tekkon was also a highly collaborative effort. I can't really imagine it being any other way. Whether as director or working as a post supervisor or doing special effects, I've always most enjoyed the projects where the contributions of all the artists working on the movie sort of felt equally distributed. Where it didn't seem like the creative power was centralised in one person. I like working as part of a large group. That's one of the aspects of filmmaking that makes it unique among all the visual arts: the fact that you have a crew of a hundred people all working toward one work of art. If you structure the process to get the best out of each of your collaborators, you can end up with something that's incredibly complex. I like both kinds of films, but I can't really imagine working like Hitchcock, who had everything mapped out in advance and who felt that the actual shooting of the film was kind of boring. I can't imagine having the best art director in the world working with me and not allowing their contribution. There is a lot to be said for that style of filmmaking, because you really do get a very pure work of art, but at the same time it's perhaps not an approach that I'm suited for.

Live action films form a kind of ideal environment for collaboration: you can take other people's ideas or take natural phenomena and make them all part of whatever you're cooking that day. That way you can come up with some very unexpected and complex scenes. On both Heaven's Door and Tekkon we had a young and very enthusiastic crew. Young veterans is the best way I can describe them. Very talented people who had been doing their thing for a while and had a lot of experience but who were also still young or young at heart and willing to try something different. That worked in favor of both my movies.

Can we talk a little bit about the main actress, Mayuko Fukuda? It's a very challenging piece for such a young actress, because to me at least, her character is very much the emotional center of story.

The film starts out very much centered in the guy's world and then at some point it makes a shift: she takes over as the center of the movie and he assumes a role that's subordinate to hers. The point of view also changes, we go from seeing things through his eyes to seeing them through hers. At the end of the movie she definitely is the emotional center of it. As the guy gets weaker and weaker I wanted us to feel that she is getting stronger and stronger. There's almost a maternal instinct in her that takes over.

That was a little tricky, because Nagase's character by nature is a little easier for people to empathise with: he's just a regular guy who finds out that he has only a few days left to live. She is something quite different: grown up in this sterile environment and still at a young age, she has only a few months to live. Her point of view is a little harder to grasp at first. I wanted him to be a regular guy and her to be a sort of foil, someone who disturbs his trajectory.

Tomoya Nagase and Mayuko Fukuda are both great actors, but she's a very, very smart little girl. She has been acting since she was six, but she said she only recently started really thinking about what she was doing. She always knew that she enjoyed acting, but she said Heaven's Door was the first project where she tried to think about what she was doing. Children have a way of inhabiting themselves in a very different way than adults do and we were seeing her make that transition. She's got an amazing sense of timing and she's an incredible ad-libber. An actor is not an actor if they can't ad-lib, but you can throw Mayuko into any situation and she will be very quick to get what's required. There were scenes that were quite emotional and afterward I would ask her "What were you thinking about?" and she would always say that she didn't remember anything. To me that says that she really is one hundred percent there.

I have not spent a whole lot of time around 13-year-old girls, so I was a little worried about how to approach her. A lot of the movie hangs on her performance. I was nervous about it, but then you get to know her and she is not a 13-year old at all. It's like talking to an adult, just in her approach to the role. She's read the script better than anyone else and she's asking some very serious questions. Very impressive. And yet she is a 13-year-old girl, she's there with her cell phone, doing her schoolwork, calling her parents.

How did you find her?

We auditioned that part to death. We saw all the actresses between 11 and 18, about 200 of them. There were some very talented young women, but 13-year-old girls either look 9 or they look 19 - there is no 13-year-old. That lasts for like five seconds and then they're grown up. It was very difficult to find someone who looked like what we pictured as 13. And then also to find someone who, without having it all explained, could grasp the nature of Harumi's character. Someone who's been living in a hospital for most of her life may have a very different outlook on life, may have seen a lot of stuff that goes on there, like death and aging. But at the same time she is someone who is very innocent, having grown up in a very sheltered environment. Mayuko got all that. She came in for the audition already in character. All the other actresses came in and we had some chitchat with them, asked them what their hobbies were and if they only had a few days to live how they would want to spend them. Mayu came in and wreaked havoc on this whole process. She was the last person we auditioned. She came in and totally subverted this little routine we would do with the actresses. Since by this time we had already auditioned a couple hundred girls, we had gotten it down to a real routine. It was frustrating, because we were running out of options and started to think about making the girl older or younger or more of just a normal kid. And then Mayu came in and really surprised us, really kind of controlled the whole audition, which was quite intense.

For example?

Well, we would kind of do our small talk with her and she would just hold on to a question for what seemed like minutes. But at the same time she wouldn't let you look away from her. You'd throw her the ball and she would just hang on to it and then toss it back to you when you least expected it. It was just the timing of her answers and the way she would really stare straight at you. You know, we actually went through a few scenes with her, using a young actor to play opposite her, and she just totally dominated. She was the first actress who really got it, who you could really believe.

You use that miniaturising effect that photographers like Naoki Honjo are also using to great effect in POV shots. What's great about those shots is that you get the idea that Harumi's view of the world is gradually broadening the further away she gets from the hospital.

I actually intended to do a lot more of that point-of-view stuff using shift lens. The camera and the lens are separated by accordion-like bellows so you can tilt the lens and rotate it away from the center of the actual film plane. This way you can get a plane of focus that is not in parallel with the film plane. Objects can be at the same distance from the camera, but not all of them are in the same focus. The result is that things look like they're in miniature. Naoki Honjo uses that to great effect, because he takes his photos from the tops of buildings, yet they look they were shot on a tabletop. There are technical limitations to doing that in motion pictures, so I wasn't able to use it as much as I wanted, but I definitely wanted the shots that are from Harumi's point of view to get you into her head at a pretty early stage in the film.

Once you've directed animation, you're immediately bracketed as an anime director, so this new project may come as a surprise to some. I imagine you always conceived of Tekkon as an animated film.

I thought very briefly about doing it as live action, but couldn't think of a way of pulling it off. In Japan you'd never get the budget to pull that off. I figured I could get it made in animation just because I'd been working in the field for a while. When I started out on Tekkon I was more the producer and the computer graphics director. We made a short pilot film that got some awards, but then the producers had a falling out and the money fell apart. We never got it together until after I'd worked on Animatrix, when my co-producer on that project said she could put all the pieces together.

This was Eiko Tanaka at Studio 4°C?

Yeah. She suggested that I direct it and then the guy I had already been working with, Koji Morimoto, also told me that I should direct it. He wasn't really interested anymore and wanted to work on his own films.

How did it feel to find yourself propelled into the director's chair?

I had been working in the industry long enough to feel that directing was the one thing I never wanted to do. Just because so many directors, guys with enormous talent, kind of crash and burn or see their lives fall apart. I'd never found anything that I felt I wanted to suffer for that much. But by that point I'd been thinking about Tekkon for seven years or something and I'd either make it or forget about it. That was basically the point where I was at. Thankfully it worked out well, but whenever I stopped to think about the scale of my job, how much had to be done, it was kind of like looking down the side of a cliff. Very scary. I remember that the first year I was directing Tekkon, it was painful for me to get out of bed, because there was just this huge thing waiting for me at work. And I was surrounded by all these amazing people who were all basically waiting for me to make a move. The first year was very difficult. I made a vow to myself on this new project to try and live in the moment as much as possible and not think too far ahead. A person can accomplish an amazing amount of things in three years when you're surrounded by the right team. I think there is a point of diminishing returns where it's best not to think too much about whether you can do it or not. It's almost more important to move forward than to move in the right direction. Because so much depends on who you're working with and natural phenomena, the weather or whatever. That whole process has such a huge influence on the final result. And there are certainly directors who have it all mapped out before there is anyone else on it. There are guys who can do that. Maybe it's because I've always worked as part of a team on a small part of the project, like computer graphics or special effects, that that's just the way I approach it, kind of making it up as I go along.

You said earlier that you were looking to do a live action film, so you must have gotten that dislike of being a director out of your system through making Tekkon.

Basically up 'til now, I've always done things for a while and then when I get tired of them I move on to something completely different. Even within the film industry. That's been the only defining feature of my career so far. I like doing a lot of things, but I'm kind of easily bored or, like in the case of developing software, I took it as far as I could take it. Working as an animator I'd had a good time, and even working on special effects in Hollywood I thought "Wow, this is amazing", but once you figure out the endgame, it becomes a little less interesting. I don't know, I think there is still a lot of interesting stuff to be done with directing, so I can really enjoy it.

Also, one thing I like about directing is that it's an intensely sociable job. You really have to communicate with people all the time - from the business people associated with the project to the craftspeople to even just the people hanging out at the location. Even when you direct animation there is this enormous range of people you need to deal with. It's a very intense environment to be in. Whereas when I was doing computer graphics it was much more solitary: you get fed the information and then you go and do it and bring it back. There wasn't a whole lot of interaction. When I was doing computer graphics I would go days at a time without leaving the room, I was so plugged into that world. And that was cool for a while, but then after a week you begin to get startled by people's voices and you lose the ability to deal with the outside world. Producing was interesting, but when I was working on Animatrix I felt that unless I was producing my own movie, it wasn't something I'd want to do again. I have a lot of respect for producers.

That's a rare thing to hear from a director.

Oh, you can't get anything done without them. I used to tell people that if I could be considered the father of my movie, then the producer was the mother. Or vice versa. It's an extremely tight relationship. Uda, my producer on Heaven's Door, is about the same age as me and it's always good to have someone who gives all their energy to the project. Even if the producer's tastes are different, as was the case with Tekkon and to some extent on this film as well, it's good to have someone who gives all their energy and also gives their opinion unselfishly and honestly. When you're directing you're always in danger of losing your way or losing sight of what originally got you interested in a project. It's nice to have a producer who is a kind of constant factor, so that you can always gauge your own direction of the film, even if you don't always agree on everything. On Tekkon we were in production for three years. It's very hard every day to retain the same mood you were in when you started the project. I would go through this routine: I would listen to the same music every morning, eat the same thing for lunch every day - just things to kind of remind you of what you set out to do. That really evolved into other things, after a while we switched from curry to Chinese food, then from Chinese food to Japanese food. It's nice to have some point of reference and I think a producer can be really good in that way. Also because, with animation as well as live action, the only people who are really on the project from the beginning to the absolute end are the producer and the director. There are various waves of people joining the project and stepping off. My cinematographer and assistant director, even though they are the ones I spend the most creative time with, once we're done shooting, they're gone. In that sense a producer is a real partner. I'm sure a lot of directors feel differently about their producers, though.

Isn't that also a difference between working in Japan and working in the United States?

I don't know, I've never directed in the United States. In Japan there is so little money and so little time and there are so many constraints on the project that at the end of the day everyone has to get out and push. Whereas in the United States, I guess, the average budget on a project is on a ten-to-one ratio with Japan. If an indie in the U.S. is made for ten million, an indie in Japan is made for a million. I think without much money on the line it's probably a different relationship between the producer, who is actually responsible for delivering, and the director, who handles the creative side of things.

The obvious question at this point would be: Do you have the ambition to direct in Hollywood? But where you are now was essentially a natural process in the first place.

Yeah. I didn't want to be a director. I don't know, it would really depend on what it was all about. I'd love to work with a Hollywood budget, certainly.

But you do intend to continue working in Japan, to have a career as a director here?

Yeah, I like living here and I like working here. I like the crews here, both in animation and in live action. I don't know if I've just been extremely lucky, but I want to try to continue. There is a lot of stuff that can be done here, that I can do, because I'm not Japanese. Japanese audiences like to see my films and maybe it's because they think it looks a little different or it feels a little different than what they're used to. I've been here for a long time, but I still find stuff that surprises me every day. I find even the most mundane stuff in Tokyo visually very exciting. It looks very different to me than where I grew up.

Also, for example Tekkon could never have been made in the United States. Not only because the technique doesn't exist there, but because the subject matter is too far out. I actually pitched Tekkon to a couple of Hollywood studios and they just went: "What?! Two little boys fighting against Japanese mafia who have a deal with extraterrestrials to turn an old neighbourhood into an amusement park? It makes no sense. Can you turn one of the boys into a girl?" That's the movie that got me interested in actually directing, so I feel there's still a lot of stuff to be explored here.

Would you like to do a story at some point that mixes your American background and Japanese subject matter?

Yeah, I would. I'd like to do a movie about an American kid and a Japanese kid, set in Japan. Two kids with different personalities that are thrown into the same situation. That's a bit like Tekkon and Heaven's Door as well, but in this case the kids would be from different cultural backgrounds. I think that's something I could do very well, or at least I would have a different take on it than a Japanese director or than the average American director who has not been here for almost twenty years. That's something I'd like to do, maybe not as the next movie but after that. I don't know how long the good luck is going to continue.

It sounds like there's a motif developing in your work already.

It's just stuff I'm really interested in.

Because of your own kids?

Well, not directly. I do see a lot of it reflected in them. It's something that fascinates me, something that I really like about Taiyo Matsumoto's work and which he explores in almost all his stories. It's the thing that got me hooked on Tekkon: this feeling that for all the defective parts that you've got there is someone else who's got a replacement for those. For all the stuff that you haven't worked out, there is another person somewhere that has it all figured out. You can say it's like a yin and yang thing, but it's not just feminine and masculine or black and white, but something a little messier than that. I see it in the relationships of these characters that I'm attracted to. I don't know, I'm still working it out myself. But having two little boys does give you a unique perspective on that. In the case of my kids, they've got completely opposing personalities and yet they're going in the same direction and they're very dependent on each other at the same time, which gives rise to very interesting situations.

You were the first person signed up for Asmik Ace's new artist management program. Could you explain how that came about?

I'm not sure if the chicken came first or the egg came first. Another Asmik producer, Shinji Ogawa, had been talking for a while about doing this artist management sort of thing. At the same time we were talking about starting Heaven's Door. And more or less synchronous to that I asked them to put me on staff. Because after Tekkon I was basically without a paycheck for a year. But at the same time I was working, going to festivals, promoting the movie all over the world. It was nice for a while to travel and have a lot of nice people take me out for nice dinners. It was really fun, but at the same time I was having a hard time paying the bills. I told the Asmik folks and the folks at Studio 4°C, and got a couple of cool jobs out of that: a three-minute this, or a short film "to help you get by until your next big project". That was okay too, but it was the first time that I didn't have a steady job in twenty years, the first time I had to borrow money from my parents since I got out of high school. So I asked Asmik before I started on Heaven's Door to put me on staff, so that when the movie's finished I can still collect a paycheck while promoting it, but I can also do other stuff for them - produce a commercial or two, or direct something, or whatever. They can keep me as busy as they want.

The week after I finished Tekkon, the head publicist of the project gave me a thousand dollars and told me to use it for travel, cab fares, and so on, because he said they were going to keep me very busy during promotion. It was two months before the release and I was basically doing interviews every day. So I thought: "A thousand dollars. This is great. I can go buy myself a suit for the premiere at the Tokyo International Film Festival". So I went out and spent the whole thousand dollars. And then two months later I realised I hadn't gotten a paycheck in two months. I went to Studio 4°C and they said: "Well, the movie's finished. What are we supposed to pay you for?" I went around and complained to everyone, and they all said: "We're sorry, but this is the way it's done." I talked to Asmik, they would say "The live action directors don't get paid to promote their films. They get paid royalties from the moment their movies get released on DVD." And I said: "Yeah, but this is an animated movie, I'm not getting any royalties. That's not the way the animation industry works."

The screenwriter of Tekkon, Anthony Weintraub, who is my best friend from college, I told him the same story while it was happening, and he said: "Well, if you can't pay your heating bills, you can always burn the suit." (laughs) I wasn't laughing at the time, I assure you. At the same time I really liked working with Asmik and they were very positive about designing a kind of umbrella for me with the assumption that I will keep making movies with them.

And if you work with somebody else they still get a piece of it?

Yeah, they can just be agents for me if they want.

Which directors, Japanese or otherwise, had an impact on you?

Among Japanese directors, probably Shohei Imamura. Not all his movies, but Pigs and Battleships is a real favorite. I never get tired of it. A couple of his other movies as well, but mainly that one. Akira Kurosawa, of course. Nagisa Oshima's movies of the 1960s, from Death by Hanging to The Ceremony, that period. There is something about his films that reminds me of - and you'll probably laugh - David Cronenberg. He's like a guy who kind of invented his own filmmaking. Especially when you get to The Ceremony, his films are so polished and refined, but at the same time it's breaking a lot of conventions. There is a very different feel to them that is very hard to describe. With Cronenberg's stuff I also feel that you can look at each film and see that he is trying out different stuff and is also getting better at it. There's a couple of his movies that are so hermetically sealed that you can't poke a hole in them. But they only work on their own terms. Like Dead Ringers. A History of Violence is completely perfect, but at the same time it's got this strange mood, where you think, "Why am I watching this?" He's made some bad movies as well, but some of his stuff is just awesome. He is a smart guy, he made it all up himself. I worked with him once, many years ago, on M. Butterfly. Not his best film, or at least it wasn't the Cronenberg movie that I wanted to work on. But I was very excited to work with him and he's an amazing guy. I got to spend a few days with him and there was this very restrained, Canadian kind of atmosphere, but at the same time it was very circus-like. He's got the same people he always works with, Carol Spier, Peter Suschitzky - they do the same stuff every time and they're all getting better at it. At some point their own technique overtakes the technology or synchronises with it, I don't know what it is. And with some of Oshima's movies I get the same feeling.

Tekkon was a manga adaptation. Heaven's Door is a remake. Do you feel there is a shortage of original ideas in the Japanese film industry?

It's definitely a shortcut to getting things made. It's very easy for a producer to bring up something that is all worked out already. But that's half the story. The other half, certainly with adapting manga, is that there is an amazingly rich field to be mined there. You could argue that manga has surpassed literature in terms of the variety and depth. You can never run out of stories, just turn to manga. It depends on what a filmmaker wants to do and what they want to get out of it. If it starts with a producer, you can just take that, find a director, cast actors - it's very easy to make a flow chart or some kind of presentation graphic to show how it's all going to fit in once you've got the money in place. There is definitely a dark side to that, it's maybe a trap in a way. I could probably spend the rest of my life directing adaptations of Taiyo Matsumoto's work and I'd be very happy to do that. But at the same time I don't know if it's right for a whole industry to have that same attitude.

The flipside is that gets harder and harder to still get original ideas produced.

Especially considering that Japanese cinema, certainly until the 1980s, was amazing stuff, and for the most part it was original. At least there were some amazingly original films that had no precedent. The one thing I think about manga and adapting works from other media, is that depending on the material it can help you get past the first level, but it's also very difficult to do anything beyond that, because of the pull of the original work. Especially in animation. It's very difficult to base animation on a manga and do anything different with the visuals than what is laid out in the original. It's too close to home. So you end up doing maybe a shabby thing that looks like it's trying to approximate the original but doesn't quite make it. Because manga and animation are totally different. When I look at Tekkon now, I feel I stayed pretty close to the original, but while I was doing it I felt like I was doing something completely different. Like I would have to apologise to Taiyo every time I saw him. But he would always encourage me to throw stuff out and do whatever I wanted. Now that I can look at both of them from a distance, I realise that anyone can see it's the same universe.