Bad Boys

- Year

- 1959

- 1961

- Original title

- Furyo Shonen

- Japanese title

- 不良少年

- Director

- Cast

- Running time

- 89 minutes

- Published

- 22 April 2010

by Rea Amit

The social problem of juvenile delinquency has been dealt with in film numerous times in various parts of the world. In the West Buñuel's The Forgotten Ones (Los olvidados, 1950), Nicholas Ray's Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and Truffaut's The Four Hundred Blows (Les quatre cents coups, 1959) immediately spring to mind as early cinematic exposés of troubled youth.

From then on, in each and every decade of the 20th century, the same topic played a significant role in many remarkable films, such as Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (1971), two features by Francis Ford Coppola in 1983, The Outsiders and Rumble Fish, and Larry Clark's Kids (1995). This continued throughout the first decade of the third millennium with notable films like Fernando Meirelles's City of God (Cidade de Deus, 2002). There are many other films that also focused on a certain kind of "juvenile havoc", perhaps too many even to list.

Of course, Japan and Japanese cinema are no exception; during the second half of the 1950s a sub-genre dedicated to the depiction of unrest among the youth came to be known as taiyozoku (sun-tribe), after a film adaptation of a novel by Shintaro Ishihara which was directed by Takumi Furukawa, Season of the Sun (Taiyo no Kisetsu, 1956). Other noteworthy film adaptations of Ishihara's novels associated with this "tribe" from the same year are Ko Nakahira's Crazed Fruit (Kurutta Kajitsu) and Kon Ichikawa's Punishment Room (Shokei no Heya). In addition, later, more risqué and far less trendy films that also deal with delinquent youth came to be proverbially known as the Japanese "Nouvelle vague". It is possible to think in this context of Yasuzo Masumura's Kisses (Kuchizuke, 1957) which may be identified as a transitional film between the sun-tribe and the New Wave, and of three significant works from the year 1960: Koreyoshi Kurahara's The Warped Ones (Kyonetsu no Kisetsu), Nagisa Oshima's Cruel Story of Youth (Seishun Zankoku Monogatari) and Kiju Yoshida's Good-for-Nothing (Rokudenashi).

Susumu Hani's first fiction feature Bad Boys was shot in 1959, and the director had a tentative agreement with Daiei for its screening, yet, fearing all of a sudden that the movie was too revolutionary in its style, the company reneged on this agreement. Hani, who had then just got married, decided not to deal with this problem immediately, and went instead on a prolonged honeymoon in Europe. After being pressured to set up a regular screening of the film by many people, most notably by the director's earliest supporter, film critic Choji Yodogawa, Hani came back to Japan and signed a screening contract with Shintoho. As a result the film finally unspooled almost two years after it was finished, in 1961.

Similar to all the titles mentioned above, Bad Boys is a straightforward depiction of troubled teens that fall into petty crime. Yet, it is altogether different. That is not to say, of course, that all the other films look very much alike, but rather that Hani's cinematic effort is unique amidst these titles, first and foremost in its means of depiction.

Bad Boys is made in an almost cinema vérité style. It was shot on real locations with non-professional actors, for whom this would be the first and last performance in film. Hani spent most of his time in the second half of the 1950s directing documentaries, which is why, perhaps, the movie begins with a warning saying that even though the film is made in a "documentary-like recording style", it is not actually so. However, another interesting factor also links the film with the modern history of the documentary genre in Japan; that is the collaboration with Noriaki Tsuchimoto, the renowned documentarist, who worked on this film as an assistant director, just a few years before establishing his own reputation.

Despite the fact that the film is based on a novel (Tobenai Tsubasa by Aiko Jinushi), and also that Hani does follow a fictional plot, he nonetheless avoids taking too much control in fabricating the scenes. Apparently, while Hani did have a written script, he followed it very loosely, if at all, not even allowing the actors to glance at it. They were given a limited scenario in each scene, creating a situation where they were to interpret and to imagine for themselves how they would have responded had the events actually been happening to them.

The result is that many of the scenes are entirely improvised, and the rest are at least semi-improvised and therefore not very dramatic. In sharp contrast to the nihilistic, nonchalant, cool, detached, or even existential characterization of youth in the taiyozoku and the so-called New Wave films, Hani's characters are simple, down-to-earth and normal, almost too normal.

The film opens up with real documentary footage of a member of the imperial family visiting what was then Tokyo's most luxurious quarter, Ginza. The following sequence is of a police prisoner transfer truck overlaid by a young man's voiceover narration saying that the only time he had seen Ginza was through the windows of a police vehicle. This was enough to place Hani on the social left wing of the political map, alongside Oshima and Yoshida, and far from the bored bourgeoisies depicted in the film adaptations of Ishihara's novels. This is not surprising at all, as Hani is the son of Marxist scholar Goro Hani, who was also among the best-known advocates of the "New Left" revolutionary ideas. However, it would a mistake to pigeonhole Bad Boys as a mere socio-economic critique, since Hani goes much further into an experimental domain of filmmaking and storytelling.

The main protagonist of Bad Boys is Hiroshi Asai, an 18 year-old Tokyo resident who is arrested with his friends after a committing a robbery at a fancy Ginza jeweller's store. From now on, Hani will very intimately follow Asai's routine in the imprisonment facility were he is put, including occasionally sharing with the audience his thoughts via voiceover. Yet every so often, Hani will also briefly shift point of view to a few of Asai's cell mates, even to the extant of straying away from him altogether to enter the flashbacks of other prisoners.

We learn of Asai's background right at the beginning, when he is interviewed by an official after his hearing, and before he enters the correctional institution. We learn that his father perished in the war and that his mother left him at some point in his life. He is hence homeless without any chance to make it in life. After being arrested, his partners are set free, due to their higher social status. Asai is then examined by several psychiatrists who find it rather difficult to determine his mental state, and therefore subsequently prescribe some "peace and quiet" in the facility he has been taken to. One of his released friends is then seen returning to his previous life, including going back to school. He is warned not to get in touch with Asai, the "bad boy".

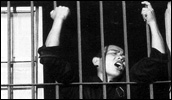

At the reformatory, Asai starts a new life alongside other "bad boys" like him. The rules there are extremely strict and everyone is forced to participate in rigorous, militaristic physical training. All the inmates are divided into groups that sleep, work and march together. Asai is placed in one cell where he is physically and mentally abused by some of the senior cell mates. This drives him to the unavoidable stand against those who are bullying him. He tries to plan a revolt against the seniors with the other cellmates who suffer equally at their hands, but when the time comes they fail to back him up and he ends up facing his aggressors all alone. Naturally, he loses and is severely beaten. However, something good does come out of this as he is then moved to another cell.

Now, working with a group making furniture and doing other woodwork, Asai finally starts to fit in. He forms some closer relationships with his co-workers and learns about their lives and the reasons that brought them there. Hani oscillates between depicting the present-day activity at the reformatory and flashbacks of the previous lives of the kids before entering it, when they were "bad boys", accompanied by composer Toru Takemitsu's bittersweet and nostalgic melodies that usher in many of the reminiscent scenes in the film. It then seems that a real bond is starting to tie him in his new group, especially in the climactic scene of the reformatory festival. But then, all of the sudden, he is set free. Again, there is nothing too dramatic in the departure scene. The door is open and he exits through it, with another dreamlike melody by Takemitsu.

It should be noted that the legal term for juvenile delinquency in Japanese is in fact not "furyo shonen", but "hiko shonen" (or "shonen hiko"). "Furyo shonen" is an abbreviated version of "Furyo koi shonen", or "youth who acts wrongly", usually referring to morally questionable behavior by youngsters. This is a seemingly strange choice of words on Hani's part, as the audience learns that there is nothing inherently "bad" or morally corrupt about the characters depicted in the movie. Most of them seem to be just victims of harsh circumstances, deserted and hapless in a society which doesn't care about them, suggested by the title of the novel the movie is based on, which translates as "Wings that cannot fly".

Yet the ethical part of this film takes place where no novel can take place, by virtue of the actors in the film, most of whom were previously detained in some sort of reformatory themselves. For them, it might be speculated, coming back to a real reformatory, after being released, and trying to react, as themselves, to situations so near their own experience, even though fictional, might have moral implications as well. For these actors, coming to terms with their former selves might have been a truly emancipating experience, not just in the literal sense of the term, but also in the broader, ethical and even metaphysical sense as well. Seen from this light, the term "bad boys" does not refer here to the kids the audience is observing, but rather to the actors themselves. For them the film functions as self-criticism of themselves by themselves. As a matter of fact, at least for one of these kids, Koichiro Yamazaki, who plays the role of one of the inmates in the film, this experience had far reaching implications, as he was given a position of an assistant director for short documentaries in Iwanami production company immediately after his appearance in this film [ 1 ] .

Bad Boys is an extraordinarily multi-layered and a multi-functional film which is also a brilliant cinematic experiment that only a few directors would dare undertake, even more so as a debut feature. The film was received by critics with a great deal of enthusiasm and was chosen by many as the best picture of the year, leaving Kurosawa's Yojimbo in second place. This led to much upheaval among Toho's executives who refused to accept the fact that a film by a young director, who never even had experience as an assistant director on a fiction film, with no stars and thousands of times less funding, could come before their world-acclaimed director.

[ 1 ] Yamazaki was later promoted to a director position, but, sadly his career was shattered after he had a near-fatal car accident which left him completely paralyzed.