Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children

- Year

- 2005

- Original title

- Fainaru Fantaji VII Adobento Chirudoren

- Japanese title

- ファイナルファンタジーVII アドベントチルドレン

- Director

- Cast

- Running time

- 100 minutes

- Published

- 28 September 2011

by Adam Campbell

As I write this, Final Fantasy: Advent Children is the number one DVD in Japan, having sold over 420,000 copies in the first week of release alone. The root of its success must surely be the large fan base that the Final Fantasy series of videogames enjoys. To the less console friendly, though, the name more likely invokes memories of Square's muddled Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001), the company's first attempt at a computer animated feature film.

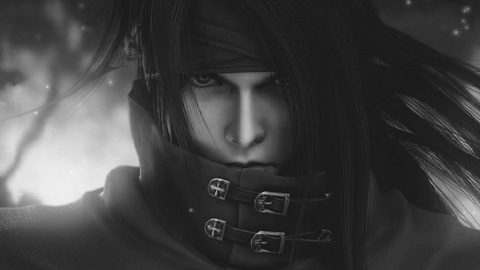

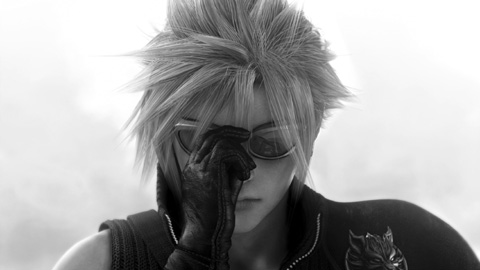

Returning to the CG field, Advent Children makes a visual departure from the previous movie in eschewing claims of photo realism and settling for a more stylised depiction of the characters and landscapes. Director Tetsuya Nomura makes his living as a videogame character designer, where his style can be recognised by spiky hair, wallet chains and an adherence to the dregs of Japanese street fashion. Advent Children features the spiky haired, wallet chained Cloud, a rebel loner. We know he is a rebel loner because he refuses to answer his mobile phone when people call him, a crime punishable by death these days. He also rides a motorbike, should the point need any further clarification.

The plot is tenuously thin, and frequently goes nowhere. It is often impenetrable to newcomers and more of an excuse for a series of battles than an actual storyline. This would be passable had writer Kazushige Nojima not insisted on including scenes of mystical-ecological mumbo jumbo and shallow introspection. It seems anyone involved in the videogame industry can't go ten minutes without praying to either of these two gods. Set several years after the end of the game, hero Cloud Strife (Takahiro Sakurai) runs a delivery service with the aid of his partner Tifa. On his deliveries, he is attacked by three brothers who claim Cloud as one of their clan and hound him as to the location of their mother, an alien head in a box. It almost sounds like the beginning to a new Miike film but don't get too excited, there is nothing so interesting going on here. Cue a hundred minutes of tedious fighting and moralising.

One of the more curious aspects of the film is Cloud's relationship with Tifa, voiced by Ayumi Ito of the Shunji Awai films Swallowtail Butterfly (1996) and All About Lily Chou-Chou (2001). Their sterile interactions recall Hong Kong films of the 1980s, where lovers seemed more like reserved platonic life-partners, and Chow Yun-Fat slept in bed with his jumper on. Cloud and Tifa share a business and raise two children, who tellingly are not their own. Rather than a wedding ring, both characters wear a matching red ribbon tied around their arm. They sleep in separate beds and their adult love affair seems relegated to dewy-eyed stares or other stalwarts of pubescent romance. A cynical critic may wonder if any possible romantic element of the film was curbed to appeal more to the designated audience of socially awkward teenage boys.

What the movie tries to deliver is action, with a number of extended fight sequences littering the film. Unfortunately, almost all of these break central tenets of action direction. On a basic level, acrobatic feats are not impressive if they are not being performed by a human being. Second, casting away the rules means casting away excitement. Several times the film breaks its own movie logic, effectively undermining itself. For instance, if Cloud can survive a fall from 200 metres and land on his feet, why should we worry if he tumbles from his motorbike? If he can deflect bullets from his sword, where is the danger in him being shot at? If neither party can come close to hitting each other, why watch them cross swords? These contradictions of attention lead to most of the battles, upon which the film is hinged, becoming entirely tedious.

Not that the blame rests squarely on the choreography. Tetsuya Nomura and Takeshi Nozue show themselves perfectly incapable directors, taking full use of their virtual camera to disorientate and annoy the viewer. The directors have obviously never heard of a camera move too intrusive, as they swirl their digital lens up into the air and spin it around each and every character as soon as they do so much as stand up. Quite how the poor workmanship on display made it through the no doubt lengthy animation process unchecked is perhaps the greatest mystery of Advent Children.

The film gained unwarranted prestige by being screened at the Venice and Montreal film festivals. Imagine the surprise of Venice when the 25-minute demo version shown at the 2004 festival made as much sense as the full 100-minute version shown in 2005. Advent Children has little to offer anyone except as an expensive fan fiction, or an occasionally impressive demonstration of some powerful animation technology that will hopefully be put to better use in the future.