Kwaidan

- Year

- 1965

- Original title

- Kaidan

- Japanese title

- 怪談

- Director

- Cast

- Running time

- 183 minutes

- Published

- 7 March 2007

by Dean Bowman

Made in 1965, not long indeed after the similarly epic Lawrence of Arabia in the West, Masaki Kobayashi's episodic compilation of ghost stories, recorded from Japanese oral folk tales at the turn of the century by multicultural expat Lafcadio Hearn, has interestingly undergone many levels of translation: from oral tradition, to text, and then to cinema; but also from Japanese, to English, and then back to Japanese. It could stand as something of an inverted embodiment of Japanese film practice in that period, in which directors were influenced by western cinema, either consciously or as a result of political machinations such as the American occupation, but also often turned that influence back upon its source.

The first thing one notices when comparing Kwaidan with the original stories, versions of which are reprinted in the generous booklet accompanying Eureka's recent release of the film, is how respectfully Kobayashi has stuck to his source. Despite this, Kwaidan remains triumphantly cinematic; featuring some of the most unique, expressionistic set design ever seen and shot in luminous colour scope compositions that almost bring tears to the eyes. It is no surprise that the film's trailer boasted its unprecedented 350,000,000-yen budget and claims that Kobayashi has enacted a 'revolution in cinematic technique'. But the advertising campaigns of studios are inevitably generous, and just as Toho praised Kobayashi's achievement to the high heavens in more public arenas, they simultaneously gave him his marching orders for his uncontrollable nature and for haemorrhaging cash - the super production's budget apparently ran out two thirds into the film. With its three hour running time, coupled with the fact that it had to be shot in a converted aircraft hanger because no sound stage was big enough, it is clear that Kobayashi had made no compromises. This, coming as it did in a time of recession and dwindling audience numbers for Japanese films, was unacceptable to the studios, which were trying to maintain tighter reigns on their directors, many of whom had consequently gone independent.

The final story of the quartet, In a Cup of Tea, relatively brief and intimate compared to the preceding three, provides a fitting cap to the project by recounting a ghost story that has itself been only half finished, hinting that the same fate may have presented itself to the film on occasion. The meta-story of this segment, which follows a retainer named Sekinai who drinks the image of a samurai reflected in a cup of water and is later made to pay for his callousness, ends with the narrator appealing to the reader's imagination to provide a suitable 'consequence for swallowing a soul'. Kobayashi, who frames the story in the Meiji period where it is in the process of being written, adds his own suggestion, and by doing so claims authorial control over the work. Calling around to wish his client new year's greetings, a publisher finds the writer to be absent. He leafs through the sheets on the author's desk and as he reads the story's final words in a somewhat dissatisfied tone - the appeal to the audience to create their own ending - the wife lets out a scream as she goes to take a pitcher of water from the cauldron in the centre of the room. The camera then pans slowly over the lip of the cauldron to reveal the author, which is as much to say Kobayashi himself, submerged in the pot entirely with only his right hand thrust towards the camera as though waving goodbye. This reflexive touch seems to hint at Kobayashi's expulsion from the studio, effectively cutting off the narrative of his commercial career. He was able to bounce back with the independently produced Samurai Rebellion (Joiuchi) in 1967, only then joining fellow humanists Akira Kurosawa, Kon Ichikawa, and his old mentor Keisuke Kinoshita in forming the production company 'The Four Knights', whose first and only release was Kurosawa's failed Dodes'kaden (1970). One can only imagine what achievements might have followed Kwaidan if Kobayashi had been allowed to retain large budgets and the favours of the studio system.

More often than not a large budget only compromises a director's vision, distracting from his themes by placing spectacle above creativity, as we are witnessing with the fifth generation directors in China such as Chen Kaige and Zhang Yimou. This is partly true in Kobayashi's case, where the extra production values have resulted in a cornucopia of stunning creativity, albeit one that avoids the kind of explicit social critiques found in the vast majority of his films, most notably his masterpiece Harakiri (1962). This has led many critics to see Kobayashi's big project as somewhat indulgent; Donald Richie referring to it as 'gorgeous pageant-like entertainment, all of it paper thin'. Certainly the style here is nothing like the rigorous, brutal realism of Harakiri, which debunked the inhumanity of the samurai code through its tightly composed images (indeed this was also the strategy in Raise the Red Lantern, Zhang Yimou's masterpiece of former times). Comparisons could even be drawn to the final film of Kurosawa, Dreams (1990), which strung together six formally experimental and surreal sequences filmed in saturated tones with an unusually wishy-washy social message. Rivalling silent era works such as D.W. Griffith's Intolerance for scale, each of the film's extravagant sets has a vast hand-painted sky; adorned with tongues of flame, huge burning stars or eyes eerily looking down from the darkness. But in this case the complete disregard of realism works, giving the film its incredible expressive force; constructing an atmosphere that is truly haunting.

Kwaidan harks back to a time when the ghost story was not a vehicle for delivering as many gore-ridden shocks to the audience as possible, but was concerned with creating a dense emotional atmosphere, rich in poignant moments of sadness and a pervasive sense of loss. Like his contemporary Kaneto Shindo, whose films Onibaba and Kuroneko are amongst the most famous of that period's 'kaidan' (the Japanese term for ghost story, the genre from which Kobayashi's film derives its name), Kobayashi uses the supernatural world as a pretext to make a highly poetic foray into the human consciousness. A far cry from the kind of J-horror used as a blueprint to revive the horror genre in Hollywood, Kwaidan is set in an ancient world, not so very different from our own in this sense, in which the most horrific thing is often not the ghost, but the human spirit. This is something that Kobayashi has had ample experience in laying bare, his previous films including The Human Condition trilogy (1958-61), which explored Japan's descent into cruelty in World War II.

As with the epitome of the kaidan genre, Kenji Mizoguchi's Ugetsu (Ugetsu Monogatari, 1953), the ghost is used as a device to reveal man's folly and weakness. Indeed the first tale that makes up Kobayashi's quartet, The Black Hair, bears striking similarities to Mizoguchi's moral fable. It follows an arrogant samurai who divorces his loving wife to pursue a more lucrative position in another city, by remarrying into an influential family. His new wife only brings him misery, but when he finally sends her packing and makes his way back to Kyoto in a vain attempt to regain his old life, he ends up spending a perfect night not with his wife but with her lingering spirit, still sitting at the loom where he left her all those years ago, her house literally falling apart around her. As with the ambitious potter in Mizoguchi's film, whose wife is raped and killed by rampaging samurai whilst he is out seeking his fortune in war profits, the samurai here is briefly reconciled to his wife from beyond the grave, before realising that the damage is already done. The main difference here is that Kobayashi punishes his samurai by having him wake up next to his wife's decayed corpse, whose long black hair, in a dark conclusion absent from the story, begins to asphyxiate him. To the contemporary viewer this moment cannot help but recall the longhaired harpies that populate current Japanese horror cinema, particularly the Ring cycle.

In the main part, though, Kobayashi's film is elegantly paced and almost classical in tone, despite its expressionist sets and a brilliant atonal score by Toru Takemitsu - indeed these modernist elements are precisely what make the film classical in the Japanese context. The languid pacing is most apparent in the film's second part The Woman in the Snow, the tale of an ice spirit who spares the life of a handsome wood-cutter (Kobayashi regular Tatsuya Nakadai) after he witnesses her killing his father, swearing him never to speak of the incident on pain of death. She later returns to him in human form and becomes a perfect wife before his inevitable confession ends his happiness. This rather harsh warning on the transience of perfection and the egotistical tendency for some men to speak more than they should has a perfectly melancholy tone, which is developed by the stark, snowy, and ever-so-slightly-obviously-fake landscapes. Also apparent here, and elsewhere, is a brilliant use of lighting, which is able to transform the loving wife into a vengeful ice sprite in the blink of an eye, before leaving her husband crying alone in a pool of light thrown by the open door. In a period when directors of the new wave were forsaking the studios in favour of raw filmmaking on the streets, this is a film that time and again highlights the aesthetic advantages of shooting on a set in which a director's vision can be fully realised and bought to bear on all formal elements. The resulting artificiality, along with the sumptuous but perfectly realised colour schemes, only add to the film's pervasive sense of absence.

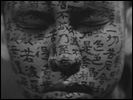

This absence, or more appropriately a Buddhist notion of emptiness, is more fully explored in the third, and best, part of Kwaidan, entitled Hoichi the Earless, which follows a blind priest's encounter with the spirit world. This sequence opens with soundless shots of the crashing waves, the lack of sense underscored by Takemitsu's discordant sounds, before the camera pans up to reveal the eponymous Hoichi standing on the edge of the shore. The film then proceeds to relate, in an eerie traditional chant, the story of an ancient battle between the Heike and the Genji clans, in which the former was decimated, leading to the haunting of the shore by malevolent spirits even 700 years later. It is clear from this introduction, which lavishly recreates the battle in a series of highly stylised and theatrical shots, climaxing in the child emperor's nursemaid leaping with babe in arms into the churning blood-red sea followed by her entire entourage, that this is the episode that cost the film the larger part of its budget and pushed the set designers and actors to ever greater heights of expression. Hoichi, a master reciter and player of the Biwa, is left alone at the temple by his master only to be approached by a ghostly samurai who leads the young man to believe that he has been explicitly requested to perform in secret to a great lord travelling incognito. Like the potter seduced by the compliments of the ghostly lady in Ugetsu, Hoichi is potentially led to his own destruction through an appeal to his vanity, which is symbolised by his blindness. The result is the most flawless, haunting, and atmospheric sequence in the film (perhaps any film) in which Hoichi, entirely oblivious to his surroundings, entertains the court of ghosts, his music evoking their sense of sorrow and nostalgia so strongly that the area becomes flooded with water and the sound of battle.

When his master (Takashi Shimura) recognises the danger his novice is in, he meticulously paints a sutra over the bare skin of the boy (a scene that might have inspired Kim Ki-duk in his elegant Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter and… Spring). Later, when the ghostly samurai comes to collect his charge, all he can find is a pair of ears floating in the air (the only part of the monk's body not covered in kanji), and wrenches them from the boy's head so as not to return empty handed. The special effects here are a subtle and effective use of matting and double exposure that recurs throughout the film. The Heart Sutra that adorns Hoichi's body suggests that the attainment of enlightenment is achieved through the realisation of the emptiness of all things and ironically contains the line 'so, in emptiness, there is no body, no feeling, no thought, no will, no consciousness. There are no eyes, no ears, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind.'

Before Kwaidan Kobayashi had utilised a formally classical style to shoot his masterpiece Harakiri, where the ritualistic nature of the samurai code was reflected in the ceremonious movements and symmetrical framings of the camera only to be disrupted by the disjunctive cutting and canted angles used to depict the act of suicide itself, making it an interesting bridge between the humanism of Kurosawa's jidai-geki and the radicalism of the new wave. Kwaidan is even more traditional (or modernist) due to the influence of kabuki theatre in its set design, particularly in the Hoichi episode in which the events are chanted in a highly ritualistic manner, leading many to see it as a kind of regression in his oeuvre. In this case the sense of emptiness that the film evokes in its all pervasive atmosphere is perhaps linkable to the traditional Japanese notion of mono no aware, which many critics see as central to Japanese films up until the fifties (particularly those of Yasujiro Ozu, Mikio Naruse, and Kenji Mizoguchi), and constitutes a kind of Zen like acceptance of the inevitability of the passage of time and of human suffering, as well as an implicit acceptance of the status quo. In a body of work as politically engaged, controversial, and committed to resisting authority as Kobayashi's the exception of Kwaidan may stand out all the more clearly, for good or for bad. Kobayashi deserves to be forgiven for this one digression from politics and into the realms of pure fantasy and form, the result of which is, after all, a magnificent and perhaps unparalleled visual achievement.