A History of Sex Education Films in Japan Part 2: The Post-War Years and the Basukon Eiga

- published

- 22 March 2007

At the end of World War II Japan was confronted with a serious problem of overpopulation. The repatriation of its citizens from the former colonies, a baby boom despite the miserable economic condition of the immediate post-war years and the resulting food shortages led to an intensive discussion of Japan's population problem. "Surplus population" (kajo jinko) became a media buzzword of the period. Birth control and family planning thus became urgent tasks and sparked the so-called basukon eiga ("birth control films") that will be the topic of Part 2 of the series "A History of Sex Education Films in Japan".

The occupation authorities were aware of the problem of "surplus population" in Japan, but they did not pursue a consistent policy as to what measures should be taken. General MacArthur held the view that ordering the Japanese to practice birth control or even ordering a national policy on the subject would be both unworkable and undesirable. This was one reason why Margaret Sanger, the pioneer of the birth control movement in the United States, was denied a visa to Japan by MacArthur in 1950. She was allowed to visit Japan only after the occupation ended in 1952, 30 years after her first visit to Japan. Colonel Crawford F. Sams, the head of the Public Health and Welfare Section of General Headquarters, also stated that SCAP policy was strictly neutral and that it was the Japanese government that had to decide what to do about Japan's population problem. In an interview in February 1946, however, Sams also argued that the Japanese had three options to come to terms with overpopulation: food imports, emigration, and birth control. Since the first two were not possible in the immediate or near future, birth control was the only option. A clear advocate of birth control was Warren S. Thompson, who from 1947 to 1949 studied the population problem for the GHQ. Thompson was a leading authority in population studies, head of the Scripps Foundation for Research in Population Problems in Ohio and the author of notable works on international population dynamics. In his 1929 book Danger Spots in World Population he had warned that Japan might solve its overpopulation problem by expansion to the Asian continent and that peace in Asia was threatened. The book generated little interest among Western policymakers at the time, but caused a considerable stir in Japan. Two translations were published in 1931, the year of Japan's invasion of Manchuria. The Japanese military welcomed the book, as they thought the recognition of its population problem helped to justify Japanese imperialism. In March 1949 Thompson proclaimed that because an increase in food production and an expansion of trade alone could not support the rapidly growing Japanese population, birth control was the only effective measure to counter Japan's "surplus population".

At first the Japanese government was reluctant to implement birth control programs. While Shizue Kato, the figure head of the pre-war birth control movement, called for effective birth control measurements and supported a revision of the Eugenic Law, the conservatives opposed the legalization of abortion. They feared that the propagation of contraception and sex education would lead to a moral decline. In 1948 the Eugenic Law was revised, but it was not before around 1950 that the government started to take a more active role in implementing a birth control and family planning policy. The main reason for this change was the post-war baby boom that had led to a sudden increase in population.

The media devoted considerable space to the debate on family planning and birth control, and the abbreviations "BC", "basukon", and "sansei" (from sanji seigen, the Japanese word for birth control) became media catchwords. Newspapers and magazines were full of advertisements for condoms, oral contraceptives, gynaecological clinics, as well as related books and brochures.

Apart from pamphlets and brochures the favourite medium for disseminating knowledge about birth control and family planning was films. At first mainly imported education films were shown, but soon such films were made in Japan as well. They were either commissioned by the Ministry of Health as, for instance, the film Boshi Techo (Maternal and Child Health Book, 1947) or financed by semi-official organisations or pharmaceutical companies. In 1947 the biggest of those, Takeda Yakuhin, sponsored the film Osan no Eiga (Film about Birth), made under the auspices of Prof. Furukawa, a gynaecologist at Nagoya University. While these early films were rather moderate in addressing sexual matters, the films made after 1949 confronted the issue in a more straightforward fashion. They came to be known as basukon eiga or "birth control films", but (as with the term osan eiga before the war) the term did not refer to a unified group of films, but to a variety of different films ranging from scientific films for medical education to alleged educational films for erotic stimulation. In the early 1950s these films were shown in cinemas, strip shows, milk bars and many other places, either in special "sex education" programs or in mixed programs together with more or less "spicy" fare.

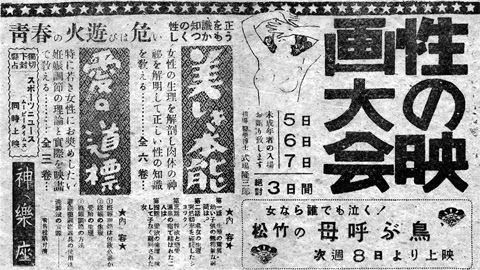

Let us take a closer look at one such program. At an antiquarian bookstore in Takamatsu I came across the handbill of a program of sex education films advertised as "Sex Film Festival" (sei no eiga taikai). From the production dates of the films and an announcement of the Shochiku production Haha Yobu Tori (first released in July 1949) it can be deduced that the program was shown sometime in 1950. The cinema where the program was shown, the Kaguraza, was not located in Takamatsu, but in Matsusaka in Mie Prefecture. It had gained some fame because of Yasujiro Ozu, who as a boy lived nearby. He later recalled that without the Kaguraza he would not have become a film director. The program of the three-day "Sex Film Festival" at the Kaguraza consisted of two films, Utsukushiki Honno (Beautiful instinct) and Ai no Dohyo (A Guide to Love). Utsukushiki Honno was produced by Rajio Eiga, an independent production company established in February 1947 by Sadao Imamura, who is also credited as the director of the film. Before the war, Imamura had been vice director of the production department of the Oizumi Studios of Shinko Kinema (today's Toei Movie Studios), after the war he established his own production company, Rajio Eiga, and produced mostly education films, scientific films and (semi-) documentaries about animals. Rajio Eiga came to fame with the sex education film Utsukushiki Honno, and Imamura continued to make sensationalist films that the Eiga Nenkan (Film Yearbook) of 1951 describes as "representative junk films of the postwar era" (sengo ni okeru getemono eiga no daihyosaku).

Utsukushiki Honno consisted of four parts: 1. "The miracle of procreation" (seishoku no kyoi), 2. "Physiology of a virgin" (shojo no seiri), 3. "Sexual desire and love" (seiyoku to ai), and 4. "The morals of passion" (aiyoku no rinri). The aim of the film, according to the handbill, was "to explain the menstruation of women and the mystery of the body as well as to teach correct knowledge about sexuality". The script was written by Ryuzaburo Shikiba, a fascinating character who was quite well-known at the time. Born in 1898, he had studied medicine, specialising in psychology, and becoming a pioneer of psychopathology (seishinbyorigaku) in Japan. Beside his work as doctor, he was a prolific writer. He published books not only on medical topics (mostly psychology), but also on many other subjects ranging from Marquis de Sade and folk art - he was a member of the mingei undo (folk art movement) of the 1930s - to impressionist painting (five dozen books on Vincent van Gogh alone). His interest in painting becomes obvious in his promotion of Kiyoshi Yamashita, a mentally handicapped painter who was praised as the "Japanese van Gogh" and who came to be known as "Hadaka no Taisho" (Naked General) (this was also the title of Hiromichi Horikawa's film about Yamashita's life). Among Shikiba's bestsellers were Onna no Kokoro, Onna no Karada (The female heart and the female body, 1937), Hitozuma no Kyoyo (Education of married women, 1940) and Shojo no Kokoro (The Heart of a Virgin, 1945), all of which dealt also with "sex education" topics.

After the war Shikiba became an important publisher. In 1946 he founded the publishing house Tokyo Times and the publishing company Romance that published among others the journal Fujin Sekai and the film magazine Eiga Star as well as Romance, one of the kasutori zasshi of the postwar years, i.e. cheap and sensational magazines with a lot of sexual content. But he also published Takashi Nagai's international bestseller Nagasaki no Kane (Bell of Nagasaki) about the aftermath of the atomic bomb. In short, Shikiba was a unique character who did not distinguish between high art and pulp, but whose main profession as psychiatrist and doctor underpinned his belief in the importance of disseminating knowledge about sexuality and sex education, whether in the form of writing or film. His cooperation in Utsukushiki Honno can be seen as a sign of his genuine wish to enlighten the audience about sexual matters. The motto of the "Sex Film Festival" at the Kaguraza - "Playing with the fire of youth is dangerous. Let's grasp the knowledge about sexuality correctly" (Seishun no hiasobi wa abunai - Sei no chishiku o tadashiku tsukamo) - may well have been by Ryuzaburo Shikiba.

While Utsukushiki Honno can best be described as a sex education film, the other film of the program, Ai no Dohyo, was a more typical basukon eiga. The handbill recommends the 21-minute long film "especially to young women" which meant women older than 20, because only adults were admitted. The declared aim of Ai no Dohyo was "to teach the theory and practice of contraception". According to the handbill the film consisted of three parts: 1. "Why is contraception important?", 2. "Pregnancy and contraception", 3. "Contraception methods: the use of contraceptives and contraception devices (hinin kigu) and the practice of irrigation (senjoho no jissai)". The full title of the film was Ai no Dohyo - Ninshin Chuzetsu o Chushin to Shite (A Guide to Love - All Around Abortion). It was produced by the independent production company Osaka Eigajin Shudan (Osaka Filmmaker Group). Little is known about the director Yutaka Takeshima except that, after the war, he directed numerous PR films in Osaka as well as two documentaries about women wrestling (released by Daiei and Shintoho), or about the scriptwriter Masaaki Nagao.

About the producer Takashi Nishihara we have rather more information. He was born in 1901 in Toyko, joined Nikkatsu in 1930 and became assistant director of Daisuke Ito. From 1934 he worked as director, directing mostly jidaigeki, first for Nikkatsu, then for Daiichi Eiga and finally for Shinko Eiga. After the war he turned to producing, he joined the newly established Toei studios and worked with directors such as Kunio Watanabe, Yasushi Sasaki and Nobuo Nakagawa. When Nikkatsu re-entered film production in 1955, Nishihara moved on to the studio where his career has started. In 1959 he again took to directing, this time educational and PR films, some of which won him the Industrial Film Award in 1969 and 1970. Among his educational films there were sex education films such as Musume ga Otona ni Natta Toki (When a Girl Becomes an Adult, 1965) or Kodomo ni Sei no Gimon ni Kotaeru (Answering the Questions of Children About Sexuality, 1965).

Ai no Dohyo was shot in summer of 1949 and got released on 19 March 1950 by Shochiku, which also distributed Utsukushiki Honno (released on 18 August 1949). On 27 February 1950, the film passed the inspection of Eirin, the Film Ethics Regulation Control Commission or self-regulation body of the Japanese film industry that had been established a few months before. The film was thought lost until a copy resurfaced in Naha on Okinawa in 1998. The copy seems to have been smuggled there, because no imports were allowed from the Japanese mainland to US-controlled Okinawa in those days. The rediscovered film has therefore been termed "yami firumu" or "illegal film". It is now stored at the National Film Center in Tokyo. It is quite harmless without explicit sexual scenes (contraception methods are explained with simple line drawing animation). The film nevertheless caused some excitement when it was confiscated on 13 November 1952 by the Tokyo police together with two other films - Wakodo e no Hanamuke (Farewell Present to a Young Man) and Kagiri naki Kodakara (Eternally Blessed with Children) - which had been shown at the Asakusa Rokku-za, the Asakusa Romansu-za and the Shinjuku Central. The confiscated print of Ai no Dohyo did not carry the Eirin mark, but instead featured additional scenes that a report in the New Year issue 1953 of Kinema Junpo described as "lascivious scenes" (senjoteki na bamen). To add additional scenes seems to have been a common practice at the time, because the films were not only shown with the aim of enlightening the audience about sex education (as perhaps the program at the Kaguraza was), but also for less noble reasons.

Around 1951/1952 the basukon eiga boom reached a peak. In addition to real educational films pseudo birth control films also appeared. Some of those films had particularly sensational titles such as Ai no Subako (Hive of Love), Shojomaku no Shinpi (The Mystery of the Hymen) or Shojomaku no Kaibo (Autopsy of the Hymen) - the latter earned the resourceful producer 3.000 to 5.000 yen per day -, but their content was in general less sensational. Apparently the curiosity of the audience to get a glimpse of something possibly prohibited or previously unseen was stronger than the frustration caused by unfulfilled expectations. Strip show venues started to show the films, and so did hot spring resorts. In his book Heso no Mieru Gekijo (The theatre where belly buttons can be seen, 1953), Fukujiro Mori, the manager of the Asakusa-za, one of the leading strip venues in Tokyo, remembers the enormous success of a mixed program with a 20-minute basukon eiga and a 25-minute live strip show for 40 Yen at his theatre: "The tiny theatre that is already overcrowded at 100 people, was jam-packed with 150 people. When some people tried to move in the crowded space that did not allow any movement, the wainscoting and the pipes behind it broke and the sewage spilled over the feet of the audience. The audience, however, didn't care at all, but continued to watch the program."

The films sailed close to the wind and sometimes crossed the legal border, as the example above illustrates, but they have to be distinguished from the stag films (waisetsu eiga, waieiga or Y-eiga) that also started to flourish at the time. These pornographic films were also shown at hot spring resorts and in the back rooms of Asakusa and other entertainment quarters, but they were clearly illegal and underground, whereas basukon eiga belonged to the public sphere. Often producers and exhibitors sought to camouflage erotic films by giving them a "medical touch" and presenting them as "sex education films". There were, on the other hand, also educational films that pretended to be lewder stuff than they actually were.

In 1952 a cinema in Shibuya, for instance, presented a "Sex education film festival" (seikyoiku eiga taikai). For an entrance fee of 100 yen the audience could watch four films: Sei no Honno (Sex Instinct), Hana aru Dokuso (Poisonous Plant in Bloom), Ratai (Naked Body) and Sanji Seigen no Chishiki (Knowledge about Birth Control). The last one was clearly a basukon eiga that was made in the late 1940s for educational purposes and approved by the C.I.E., the occupation authority in charge of film regulation. Curiously it was this film which got the cinema owner into trouble. The police confiscated the film because parts of it were considered obscene and thus in violation of §175. What had been permitted during the occupation was not necessarily allowed after Japan regained its independence. This incident, however, did not deter the owner of the cinema from presenting another program, advertised as "2nd Sex and Nudity Special" (Dainikai sei to hadaka tokushu). This program consisted of such films as Nikutai no Akuma (The Evil of Flesh), Onnakengeki no Seitai (Mode of Life of Female Sword Play) and Hadaka ni Natta Otohimesama (The Young Princess Who Got Naked). The latter was a salacious comedy produced by Fuji Eiga in cooperation with a strip theatre in Tokyo. It featured several leading striptease stars of the time such as Akemi Nara, Harumi Sono and R. Temple as well as young comedians like Norihei Miki and Nobuo Chiba on their ascent to comedy stardom.

Hadaka ni Natta Otohimesama was also part of another program that illustrates how diverse the films of such "specials" were and that different interests were at stake. In 1952 a distributor of such films ran into trouble with the local federation of exhibitors. The Kanto Koshin'etsu branch of the Japanese Entertainment Industry Federation (Nihon Kogyo Rengokai) ordered its members to refrain from showing the program, because the films were deemed "inappropriate" (amari kanshin dekinai). Such a call for self-restraint (jishuku) was unheard of and the distributor countered with the argument that all films were either approved by Eirin or the Occupation authorities and that the call was illegal, libelous and slanderous. The controversy kept the involved parties busy for quite a while, but the exhibitor lobby could not prevent the program being shown. It consisted of 8 films, among them Hadaka no Otohimesama and Utsukushiki Honno as well as Jinko Jusei (Artificial Insemination), Sutorippu Tokyo (Tokyo Strip), Osan to Minzoku (People and Birth) and Jonetsu no Hadaka Onna (Passionate Naked Women). The program is typical in its eclecticism, which can be compared to the later Mondo films. Sutorippu Tokyo was a 1950 striptease film that featured Motomi Hirose, the reigning striptease star of the Shinjuku Central Gekijo, who also starred in several Shintoho films such as Umetsugu Inoue's Seishun no Dekameron (Decameron of Youth, 1950). Jinko Jusei, on the other hand, was a film about artificial insemination of Holstein cattle, directed by Taketaka Yagisawa, a scriptwriter at Shochiku. It was first released in September 1949 as Horusutain Monogatari (Holstein Story) after Eirin had objected to the title Jinko Jusei.

With time such programs became more daring. As in the pre-war period, the line between sex education film and sex film was very fine indeed. In April 1955 the Ueno Star-za, for instance, presented a special advertised as "Treasured Clinical Medicine - 2nd Sex Film Special" (Hizo rinsho igaku dainikai naigai seieiga taikai). Six films were shown: Wakaki Hitozuma no Seiten (The Sexuality of a Young Married Woman), Jotai Shinpisei no Kaimei (Unravelling the Mystique of the Female Body), Junketsu o Nerau Otoko (Men Aiming at Chastity), Sekai Kakkoku no Seihokoku (Sex Reports from Around the World), Momoiro Paradaisu (Pink Paradise) and Chimata no Dokuso (The Poisonous Plant of Public Spaces). The program was also shown at the Fujikan in Sugamo where it caught the attention of the police. The owners of both cinemas were investigated on suspicion of violation of §175 of the penal code, i.e. distribution of obscene material. The cause of the police intervention was Wakaki Hitozuma no Seiten which originally had been made under the auspices of the Red Cross Birth Clinic in Hiroo to promote safe child birth. This typical basukon eiga - its original title was Mutsu Bunben (Painless Childbirth) -, had passed the Eirin inspection in January 1954. The print seized by the police, however, had a different title and close-ups of female genitals inserted into the film. What had not been altered was the original Eirin mark, but this was not the first time that the Eirin mark had been abused.

Such incidents gave the police a reason to crack down on offenders and put pressure on distributors and exhibitors. The boom of basukon eiga reached its peak around 1952 and then faded fairly quickly, not only because the police took harder action, but also because the initial curiosity of the audience began to wane and not least because the films of the major film studios had become more "sexy".

The discussion about birth control was, of course, not restricted to the post-war period, but continued during the period of high economic growth. Thus, the demand for correct knowledge did not decrease, and films about birth control, family planning and sex education continued to be made for public education as well as for use in schools. For instance, the JFPA, the Japan Family Planning Association (Nihon Kazoku Keikaku Kyokai), established in 1954, commissioned educational films to promote family planning. Their first film was ordered by the Ministry of Health in order to promote its birth control program. Since the JFPA did not have much of a budget at its disposal, the film is said to have been pre-financed by the later Minister for Health Tatsuo Osawa, who at the time was still only a section chief at this same ministry. In 1956 the JFPA commissioned another film, Kazoku Keikaku Daiippo (The First Step to Family Planning), which warned of the dangers of abortions and emphasized the importance of an active family planning. The 30-minute long 16mm film was produced by Erumu Eiga and directed by Kajiro Yamamoto, who had come to fame in the 1930s with comedies starring comedian Enoken. I found the film in the archive of the JFPA, but have never seen it listed in a filmography of Kajiro Yamamoto.

A survey of birth control films would not be complete without mentioning a group of films that were not made with the explicit intention of educating its audience, but that may very well have contributed to the enlightenment of some of the viewers. In the 1960s and early 1970s a number of so-called pink eiga, the Japanese variant of sexploitation films, made fun of the birth control debate. One of the first was Masao Adachi's Datai (Abortion) about a crazy gynaecologist who wants to liberate mankind from sexual problems by radically separating sex on the one hand and reproduction, which should be left to artificial wombs, on the other. For the opening scene Adachi used a birth scene from an older 16mm sex education film, either a pre-war osan eiga (see Part 1) or a post-war basukon eiga. Datai was Adachi's first pink eiga, and his next film Hinin Kakumei (Birth Revolution, 1967) again features the crazy gynaecologist, whose name, incidentally, is Marukido Sadao, a pun on Marquis de Sade. Adachi used the name again in his script for Koji Wakamatsu's infamous The Embryo Hunts in Secret (Taiji ga Mitsuryo Suru Toki, 1967) in which the protagonist is driven by his wish to return into the maternal uterus - an inventive variation of the "birth film". Adachi was not alone in mocking the birth control discourse. Shunya Yamamoto ridiculed the issue in Ninshin - Bunben - Chuzetsu (Pregnancy - Childbirth - Abortion, 1968) and Seika Sodan Kanzen naru Hinin (Sex Counseling - The Perfect Contraception, 1969), and so did Kinya Ogawa in Seiri to Ninshin (Menses and Pregnancy, 1968) and Osan to Hinin (Birth and Contraception, 1969) or Koji Seki in Koi - Ninshin/Chuzetsu (Conduct - Pregnancy/Abortion, 1973). And we must not forget Takae Shindo's Chuzetsu Shujutsu (Abortion Surgery, 1969), which was produced by the originally named production company Young Men Art Film Association (Seinen Bijutsu Eikyo).

Most of these films shared the common fate of pink eiga, i.e. they were soon forgotten. The films of the major studios dealing with the birth control issue fared rather better. Yuzo Kawashima, for instance, seized on the topic in his first film for Nikkatsu after leaving Shochiku. Ai no Onimotsu (Burden of Love, 1955) revolves around a health minister who, pressed by the opposition parties in parliament, presents a plan for the establishment of a birth control office in order to do something about the increase in population. In his family, however, everyone gets pregnant: His wife at age 48, his secretary from his son, his daughter from her fiancé, and even the young girlfriend of his old uncle, who lives at his holiday house in Hakone. The satire is a loose adaptation of André Roussin's play Lorsque l'Enfant Paraît (When the child appears) which had been staged in Tokyo by the theatre troupe Bungeiza in December 1953 under the title Akanbo Sho (Baby Sho) and which was a huge success. Kawashima could not obtain the right for a film adaptation, however, because they had already been sold to Michel Boisrond, who completed his film in 1956. Kawashima and his scriptwriter Ruiji Yanagisawa were therefore forced to rearrange the story and change the dialogue.

Birth control, contraception, and abortion as well as sexual topics were also an integral part of another group of films made in the early 1950s by the major film studios, the so-called seiten eiga or "sex encyclopedia films" which shall be discussed in Part 3 of the series.