Hideo Gosha Part 2: The Will To Live

- published

- 2 December 2013

Hideo Gosha on set in 1978

Read part 1 – Hideo Gosha: The Manly Way

Between 1974 and 1978, Hideo Gosha was unable to pursue his filmmaking career and could only make documentary films for Fuji TV. The reason for this predicament was notably the fact that director Taro Okada had more or less supplanted Gosha at Fuji TV. Furthermore, during his 4-year period making documentary films in Japan and abroad, Gosha fell victim to several smear campaigns launched by the media. He was accused of accepting bribes after a shoot (assistant editor Seiichi Sakai once told me that this affair was "the Lockheed of the entertainment business") and of belonging to a yakuza group called Soryukai, run by yakuza boss Masaji Morita. Having always had yakuza friends (including former kamikaze and yakuza turned actor Noboru Ando), Hideo Gosha was indeed rubbing shoulders with Masaji Morita, whom he admired, but was not in any way a member of his group. On account of those orchestrated scandals, Hideo Gosha found himself unable to make several chanbara films, including a proposed sequel to Goyokin, to be titled Samurai no Kiba.

Hideo Gosha surged back to fame with two taisaku mono (prestige pictures): Bandit Vs Samurai Squad (Kumokiri Nizaemon, 1978) and Hunter in the Dark (Yami no Karyudo, 1979). In a 2012 interview, actor Tatsuya Nakadai revealed how he had read Shotaro Ikenami’s Hunter in the Dark, loved its title and suggested producers Ginichi Kishimoto and Masayuki Sato of the theater-turned-film company Haiyuza that they should adapt the writer’s novels for the big screen. Being an avid reader, Hideo Gosha most likely knew the novels and their author as well. But his treatment of the novels eventually led to a sour antagonism with Shotaro Ikenami.

"Gosha made Bandit Vs Samurai Squad after a long period of smear campaigns and aborted projects," explains Seiichi Sakai, who used to work as an assistant editor to Michio Suwa and edited trailers for both Bandit and Hunter. "So Gosha used the film as a way to convey a vengeful message against society and redeem his honor. He went so far as to speak his very mind through the dialogues of characters like both Kumokiri and Shikibu Abe. Obviously, he did not abide by the literary source and changed it utterly. Shotaro Ikenami felt offended by all the changes and thought that the films were not refined enough." Indeed, the novelist so hated Bandit Vs Samurai Squad that he allegedly said after a private screening: "Why didn’t Shochiku hire a better director?"

The "vengeful" message of the film is what made Gosha give Shikibu Abe lines such as: "Are law-abiding citizens always flawless?" The promotion campaign backed the message with the tagline: "Is the hero a villain? Is the villain a hero?" Despite such rancorous manifestations, Bandit Vs Samurai Squad is first and foremost a film about a "beautiful and sad bandit" (Gosha used the word hisou, meaning sorrowful or touching), a former samurai who eventually manages to cast off his vengeful spirit in order to meditatively retire from a world ruled by ambition and vanity. This evidences Gosha’s own spirit in a film where Kumokiri and his nemesis, both turned marginals, have a brief, final encounter in a Buddhist graveyard. The scene strangely echoes the life of the director himself, who in 1975 had met a Buddhist priest in the city of Kawagoe and already booked his own grave in the city’s Buddhist graveyard.

On the minus side, Bandit Vs Samurai Squad does not really hold up to the aesthetic quality of Gosha’s previous films. The director fell out with cinematographer Masao Kosugi during production, hiring Tadashi Sakai instead (Hitokiri’s Fujio Morita was then unavailable). Moreover, the film was simultaneously shot by four units, who burned the midnight oil every day, which made the film a narrative and stylistic patchwork. According to set decorator Yoshinobu Nishioka (who also worked on Hitokiri), "Bandit Vs Samurai Squad does look like a big jigsaw puzzle, but it fared well commercially and allowed us to do Hunter in the Dark next."

With Hunter in the Dark, Hideo Gosha made his most decadent chanbara to date. The film is filled not only with great sword fights but also with sex scenes and long, bloody assaults wherein human life is but a battle of instincts and impulses against the intellect. The aesthetics already developed in Hitokiri and The Wolves reach their acme in Hunter in the Dark, as in the scene of blood dripping from a ceiling on a female stripper’s breasts, reminiscent of Hotei Nomura’s silent Don’t Fall In Love (Nasuna Koi, 1922), scripted by chanbara pioneer Daisuke Ito, in which blood already dripped down through a ceiling.

Hunter in the Dark once more portrays two men drifting away into darkness to elude the vanities of a world filled with human ambitions and manipulative power struggles. Gosha’s vision is not very different from what Kurosawa would convey in the final scene of Ran, where the character of Lord Tsurumaru overlooks the abyss of human violence and despair. In Hunter in the Dark, the character of Yataro Tanigawa finds himself surrounded by flames, beneath an impenetrable Buddha statue that can only overlook the senselessness of human violence. Hunter in the Dark was also meant by Gosha as the first enactment of an artistic manifesto whereby he would make, for a whole decade to come, wild, venomous and utterly uninhibited films, with no holds barred in the depiction of human passions and desires. "Hideo Gosha was the painter of dark passions in the human heart", said producer Kazuyoshi Okuyama (who would work with the director on Four Days of Snow and Blood / 226).

Once again, Shotaro Ikenami so hated the film that he forbade Gosha to adapt any other novel of his. The director had indeed completely changed the story and the characters so as to make them more personal. Even the final swordfight, following Gosha’s animalistic approach (the duellists fight it out near a henhouse) did not exist in the book. According to Seiichi Sakai, "the final scene also evidences new influences Gosha derived from shooting documentary films in the 70s."

Hunter in the Dark would actually be Gosha’s very last chanbara with a real focus on male characters. The film is a turning point in his cinema, before female characters and their passions take the lead. Little did Gosha know, however, that his cinema heralded the darkness to come in his life. After Hunter in the Dark, Hideo Gosha had several projects on the front burner, including documentary and fiction films. But his whole life and career came to a standstill after his wife mysteriously left home. Hideo Gosha was a traditional Japanese man, who conceived his own life as free of domesticity as possible, meaning that his wife, in true ryosai kenbo ("Good wife, wise mother") fashion, freely managed household finances. Unbeknowst to Gosha, she had given a large amount of money to bogus investors, saddling the director with a huge debt he was forced to pay off. In one brief instant, he had lost his fortune and had no choice but to move out of his cosy house in the suburbs of Tokyo. But that was not all. A few weeks after the downfall of the Gosha family, the director’s daughter Tomoe was involved in a nearly lethal traffic accident. Last but not least, another few weeks later, Gosha was arrested by the police. Back in the sixties, Gosha’s yakuza acquaintance Masaji Morita had smuggled guns into Japan and now the law was after him. They happened to find two guns at Gosha’s home and decided to place him in prolonged custody. The filmmaker was later forced to resign from Fuji TV, which meant that his career was dead and buried – or maybe that he was free at last. Back in the late 60s, Gosha still saw himself as a "farm fish". But now, the fish was forced to swim towards the open water at last.

Haiyuza producer Masayuki Sato and Toei president Shigeru Okada once again came to Gosha’s rescue, asking him to direct Onimasa (Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai, 1982). Gosha was actually a great admirer of Tomiko Miyao’s novels, which were about dysfunctional families in the region of Kochi, trapped between growingly obsolete lifestyles and advancing modernity. Miyao’s father was a kind of pimp selling young girls to brothels, very much like the main male characters in his next couple of films, Onimasa, The Geisha (Yokiro, 1983) and Oar (Kai, 1985). Since Hideo Gosha could no longer probe samurai dignity in those characters, he turned instead to aizo (love-hate) relationships between men and women.

The Geisha

The main female role of Onimasa was to be played by young actress Shinobu Otake, but she happened to turn it down on account of the eroticism of the script and Hideo Gosha’s bad reputation. Gosha was so angry that he again began to lift the elbow, but Toei simply advised him to find another famous young actress. The secret code between the director and the producers was that he would choose the actress to whom he would give Tomiko Miyao’s novel at the end of her audition. He eventually gave it to Masako Natsume. This very beautiful actress was 25 at the time and known mainly for her role in the television series Monkey and in Kanebo cosmetics commercials. She was not a recognized actress yet, but Gosha’s expert directions would allow her to prove her mettle. The director could sense some kind of pent-up anger in the young actress, who was actually very ill (she would die three years later of Graves' disease), and worked in the entertainment business against her mother’s wishes. Hence, Gosha used her anger (and his own) in the scene where she belches out the famous line: "Nametara ikanze yo!" ("Watch out! The shit's about to hit the fan!") Producer Kazuyoshi Okuyama would later say that, "only Gosha could have done a film like Onimasa, because his power of expression thrived on the negative energy given to him by the antagonism of society."

Onimasa was also a film in which Gosha inserted a scene mirroring his own life (something he often did) and his relationship with his daughter, namely the sequence toward the end of the film where Onimasa and his daughter reunite during a fireworks display. Gosha’s daughter’s health was by then improving and she would eventually become a movie journalist, something Gosha himself found a little bit exasperating. (Tomoe would contribute a very beautiful text to the presskit of The Geisha.)

Onimasa

At over 2 billion yen, Onimasa’s box office success was huge, while the film earned Masako Natsume a Blue Ribbon Award for Best Actress. Unfortunately, Gosha did not use her talent again beyond a small role in his Fuji Television (a.k.a. CX) remake of Tange Sazen (1982), which fulfilled Tatsuya Nakadai’s wish to play the character after Tetsuro Tamba in 1963 and Kinnosuke Yorozuya in 1966. Gosha would never really find another young actress with such a pitch-perfect combination of beauty and intensity, though perhaps Atsuko Asano (The Geisha, Tracked) and the more mature Kanako Higuchi (Heat Wave, The Oil-Hell Murder) come close.

After Onimasa, Hideo Gosha was back on the scene again and could make virtually any film he wanted. Of the twelve films he directed between 1982 and 1992, six were true commercial hits, his biggest box office failure being Fireflies in the North (Kita no Hotaru) in 1984. Gosha used Tomiko Miyao’s novels to further explore his own downfall and his condition as a husband, a father and a (once) proud Japanese man, leading to such catharthic scenes as Momowaka crying out "All men are enemies of women!" in The Geisha, and Iwago smashing the symbols of his male strength to smithereens in a final scene of Oar, which was written up during production.

Oar

Gosha’s films thus became increasingly female-oriented (and intimate) throughout the 80s. This was due to several factors. First of all, the failure of his marriage had changed his vision of women, and he now felt that they were essentially as battlesome and vindictive as men. Moreover, the novels by Tomiko Miyao that he loved were about men whose professions, linked to brothels – whether small-scale houses or large-scale bordello disctricts like the Yoshiwara – made women unhappy. So Gosha felt he had to portray both their sadness and fighting spirit. For instance, Gosha saw geisha as artificial flowers rooted in the mire of unhappiness caused by men. Last but not least, the vigorous actors of chanbara were now well past their forties and fifties and could no longer meet the tough physical demands of a Gosha chanbara. This led him to stage his actresses in incredibly long brawl scenes, which, according to DP Fujio Morita, served the purpose of bringing out the beasts in them and challenging the viewer’s perception of what a brawl scene could be. "To Gosha, the greatest human qualities were resilience and endurance", says Morita. What Gosha actually did was to transfer the kinetic energy of his male characters onto female characters who then took over from the director’s former samurai and yakuza, in films such as Death Shadows and Gate of Flesh.

In 1984, Hideo Gosha accepted Toei’s offer to direct Fireflies in the North, about a 19th century samurai rebellion in a Hokkaido prison called shuchikan. The Japanese government was by then using political prisoners from former samurai clans in order to build railroads in snowbound northern Japan, at a heavy death toll. The script focused on a real-life character called Kiyoshi Tsukigata (Tatsuya Nakadai) and his love affair with a mysterious woman played by Shima Iwashita (already seen in Sword of the Beast). This love affair leads to an ending that makes the film differ greatly from Gosha’s former Goyokin. Whereas Magobei eventually walked away through a field of snow with his back turned to his wife, Tsukigata decides to cast off all notions of jingi and giri in order to sing and dance with his beloved. The scene was not in the script (which even ended with different characters) and exemplifies Gosha’s wish to express his own love of life and Japan’s popular arts (especially enka) more than his admiration for the samurai or yakuza spirit.

Fireflies in the North

In 1985, the year Three Outlaw Samurai was adapted into manga form, Gosha stopped being a "farm fish" and became a truly independent director by founding his own production company Gosha Pro. A number of actors and directors had already done the same thing before him, but Gosha was free to propose his scripts to the major studios (especially Toei and Shochiku) and produce them with his own crews, namely from Eizo Kyoto. Throughout the 80s, Gosha was actually able to ensure the continued existence of big studio cinema and its traditions, which had been declining since the 1960s.

Gosha’s first film as an independent producer and director was 1985’s Tracked (Usugesho), probably his third masterpiece after Hitokiri and Oar. Tracked was based on a novel by Nozomu Nishimura about the real case of a miner turned murderer, four years after the end of WWII. Gosha said that he could understand the feelings of this man, called Sakane (Ken Ogata), who murdered wife and child before living as a fugitive for eight years. Gosha portrays Sakane as a snake (after previously likening samurai and yakuza to dogs or wolves), a man deprived of all pride and self-esteem, forced to live in the darkness of his own soul. The film boasts a complex narrative, replete with flashbacks and flashforwards, and Sakane is probably the first character in Gosha’s cinema who attemps to kill himself, only to live on and become, in the eyes of the woman who falls in love with him, a mere illusion of a man (a maboroshi). Hideo Gosha had never portrayed a man with such psychological realism, save perhaps the similarly pathetic and sorrowful Izo Okada. The Japanese critic Yoshio Tsuchiya wrote that "the film is much more unsettling and unpleasant than Shohei Imamura’s Vengeance is Mine".

Throughout the 1980s, Hideo Gosha’s movies were seldom supported by Japanese critics, who viewed his films mostly as "gaudy" or "vulgar" (being a film reviewer, writer Shotaro Ikenami had more negative things to say, for instance, about The Geisha). However, a handful of critics like Yoshio Tsuchiya, Yoshio Shirai or Kunio Kuroda went the other way and praised Gosha’s cinema, pointing out that it was filling a gap between artistic cinema and commercial film. Gosha would often say that he did not care about critics and reviews, but he secretly wished to make a film that would earn him artistic praise.

In 1986, Shochiku gave Hitokiri a limited re-release. Shintaro Katsu and Hideo Gosha were invited to reminisce about it on a television talk show, and what Gosha said about Yukio Mishima earned him the anger of a group of right-wing extremists, who went so far as to attack the director and slash his face with a knife. But unlike Juzo Itami, Gosha refused to reveal the mugging to the media. He did not want to victimize himself, nor publicize the muggers. So he simply told his friends and collaborators that he had "fallen off his bike". According to producer Kazuyoshi Okuyama, Hideo Gosha was harrassed several times during the course of his career, maybe also during the production of Four Days of Snow and Blood, but the director never said anything about it.

Death Shadows

Still in 1986, Hideo Gosha directed two films: Death Shadows (Jittemai) and Yakuza Wives (Gokudo no Onnatachi). The former was the last jidai geki / chanbara shot on the huge set of the Daiei studio in the Uzumasa district of Kyoto, before it was torn down and converted into an residential area. The film was thus conceived as a kind of celebration for a declining genre that Gosha felt had to be continually reinvented. The director’s motto was Honpo hatsukokai, meaning "Always something new", and with Death Shadows Gosha clang to that motto by introducing rhythmic gymnastics into chanbara – his very first dance-like choreographies, so to speak. The film was also conceived for another young actress, Mariko Ishihara, whom Gosha saw as having a dual personality, much like Onimasa’s Masako Natsume.

Gosha then directed Yakuza Wives, which would turn into a profitable saga for Toei. Although Toei producer Tan Takaiwa proclaimed it "all fantasy", Gosha’s film, which was a major hit, was actually based on an interview book by female journalist and writer Shoko Ieda, who had lived closely with yakuza wives for one year. Both Ieda and Gosha were fascinated by the mindset of those wives, who were both very modern and abiding by past rules of yakuza clans. They were a bit masochistic, too, which, to Gosha, was a typically Japanese trait (cf. the masochism of Izo Okada).

Yakuza Wives

The film is interesting in that it portrays two very strong women (fighting it out again in a very long punch-up) and weaker men, lost between past yakuza rites of the ninkyodo and a mindset turned toward business and profit. Unbeknowst to most viewers, the film also shows something Hideo Gosha bore on his own skin and tried as best he could to hide from his film crew, namely tattoos. Hideo Gosha had himself been secretly tattooed in January of 1983, not to become a yakuza, but in order to exorcize his growing obsession with death. Hideo Gosha knew he would not live long past his 60th birthday, and he actually died at the age of 63. So the tattoo, harbouring a demon, a dragon and a phœnix, was for him a way of strengthening his mind against death and his inner demons. Actress Atsuko Asano allegedly said that she was fed up with hearing Gosha talk about death during the shooting of The Geisha. According to Tatsuya Nakadai, interviewed by the author of this article in 2013, Gosha’s tattoo was for him a way to prepare himself for death by acknowledging the yakuza (or rather, bakuto and tekiya) origins of his family, which he had been hiding for so long, "buried under his skin" in a way. "But under the skin, we are all basically yakuza", he wrote in the press kit of Yakuza Wives.

In 1987, Gosha delved deeper into his past with the prestige picture Tokyo Bordello (Yoshiwara Enjo). It was based again on a book, a popular graphic novel by painter Shinichi Saito, which contained scenes and atmospheres of the Shin-Yoshiwara, the red light district based north of Asakusa, Gosha’s native district. For the film, set decorator Yoshinobu Nishioka rebuilt 150 metres of the 300-metre long Nakaumero, the main street of the Yoshiwara, where the oirandochu, the greatest of the courtesans (joro), lived and worked. The film was a great reproduction of that era, and a bitter film as well, with one courtesan dying like a beast after crying out in a red futon chamber. Gosha saw the Yoshiwara as one of "the deceitful illusions of the world", selling hope and love in a world driven by profiteering and human exploitation.

Tokyo Bordello

Viewers impressed (or not) by Gosha’s female-oriented films should know that the director personally rehearsed all the love scenes for his actresses, so as to help them get rid of their shame. Most actresses were inhibited by the roles Gosha offered them, and would balk at the sex scenes. But Hideo Gosha would play them first with his male assistants, which had the whole crew laughing. "For my role in Tokyo Bordello, I gave my body, my heart, my soul", later said actress Yuko Natori, who also played a memorable yakuza woman in Gosha’s Gate of Flesh (Nikutai no Mon, a.k.a. Carmen 1945). This very film was Gosha’s own version of the famous novel by Taijiro Tamura about postwar pan-pan girls (prostitutes for US soldiers), which he turned into a real female yakuza movie (the director secretly wished to direct a film like Red Peony Gambler, with Junko Fuji) and a celebration of sisterhood and human warmth as opposed to the coldness of postwar industrial society. Tamura’s motto opposed nikutai (flesh) to kokutai, Japan’s nationalistic ideology. Tamura felt that Japanese people had been deprived of the freedom to use their bodies, because they had had to sacrifice body and soul to the nation, and the return to the flesh meant that humans could strip their mind of all ideological constraints and live to the full again, even in dire straits. Though Tamura’s ideas were considered sensationalistic, they contained a sense of defiance and liberation that Hideo Gosha certainly embraced.

Gate of Flesh

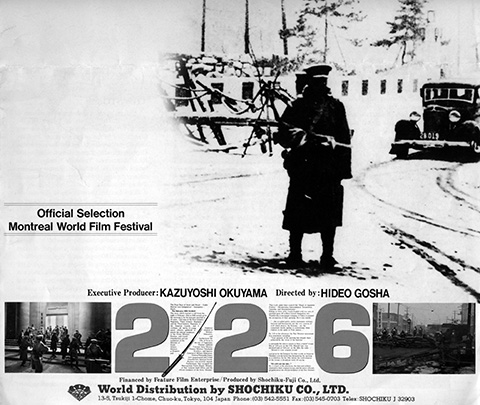

However, Gosha was getting fed up with his image as a director of erotic films and felt he could still do something different, maybe going back to his roots as a director of male-centered films. This he did in 1989 with Four Days of Snow and Blood. A few years earlier, producer Kazuyoshi Okuyama (still known to this day for releasing two versions of Rampo in 1994, his own version versus that of original director Rintaro Mayuzumi) and Hideo Gosha had met over a handful of projects, including a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Shintaro Katsu’s 1989 Zatoichi. After Katsu and Gosha had fallen out for petty reasons over a curry dinner, Okuyama decided to go with Gosha for the project of Four Days of Snow and Blood, written by Kazuo Kasahara (Battles Without Honour and Humanity), about the 1936 coup d’etat that had led to a strengthening of the toughest military faction within the Japanese government.

Four Days of Snow and Blood

Production was hampered by several difficulties, including the death of emperor Hirohito in January of 1989, which meant that any direct reference to him was hence prohibited, both in the film and the promotional campaign. Knowing that right wing extremists could be dangerous, Gosha consciously refrained from making a film that could be too politicized, opting for melodrama instead, with female characters and flashbacks not to Kazuo Kasahara’s liking. Difficulties increased when Hideo Gosha, who had a reputation for veering off scripts, had an argument with Okuyama over scenes the producer wanted to have in the film. "It’s your film! I quit!" said an angry Gosha, who added actions to words by purely and simply disappearing, forcing Okuyama to sort out the film’s postproduction. This predicament could have marked the end of an interesting collaboration between the two men, but Four Days of Snow and Blood proved to be a commercial hit, which appealed very much to young viewers.

Shortly after the premiere, Kazuyoshi Okuyama learned that Hideo Gosha was actually terminally ill with cancer, hence the reason for his disappearance. "I think the demons of death love me", the director said to his daughter in a Kyoto hospital. Kazuyoshi Okuyama asked Gosha what he wanted to do next even though he was now very weak. "I have always wanted to do a film like Red Peony Gambler", replied Gosha. "I cannot do a Toei film for Shochiku", Okuyama said. "Let’s do the film with Kanako Higuchi and give it a title that will not sound like a Toei yakuza movie", Gosha answered. Okuyama finally agreed to Gosha’s proposal, with a title of his own conception: Kagero, which meant Heat Wave and was meant to convey to the audience the feeling that Gosha’s cinematic power was back.

Heat Wave

But when Okuyama later saw the dailies, he found out that this power would not be back. Gosha was too weak and not directing his film the way he used to. Okuyama then came up with the idea of a rock song (which infuriated composer Masaru Sato), once again to convey the idea that Gosha was back on top form. The film was a hit, which gave Okuyama the incentive to produce a real saga, very much like Red Peony Gambler, maybe the first successful yakuza movie saga for Shochiku. But Gosha declined to direct a sequel. The reason was that he felt he was dying and wanted to do The Oil-Hell Murder (Onnagoroshi Abura no Jigoku) instead.

This time, there was no argument between Gosha and Okuyama, who agreed to fully support the director so as to help him direct his very last film, scripted by the great Masato Ide (Kagemusha, Ran), who died before the film was completed. Ide had written the script specifically for Gosha, telling him: "Movies of yours like Death Shadows suck! You don’t know how to portray women and their psychology properly. Use this script to do just that." Though Gosha was terminally ill and weaker than ever, he did all he could to make the artistic film he had long been dreaming of, a film that would put him on a par with the best Japanese directors. But he failed. The Oil-Hell Murder was a commercial and critical flop, and Hideo Gosha died soon after. But is the film in any way an artistic failure? It is actually very beautiful in its use of graded colours, from the greyish hues of social conformity to the reds of passion. Although Gosha tried to refine his style, make it slicker, The Oil-Hell Murder does contain his conception of human passions as a battlefield, linking them to all possible fluids (blood, semen, oil, etc.). Gosha’s passions have always been very organic, especially in the later part of his film career. He saw men and women as oil and water, and fundamentally thought that every man lives in a lonely manner, with regret as a companion, while women live in the solitude of their feelings. It was thus difficult for each not to be just living shadows, and maybe animal instincts were the only way to delve back into the whole potential of human emotions and the will to live. Gosha's ‘philosophy’ is perhaps best expressed in a wonderful formula by Samuel Johnson: "He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man."

The Oil-Hell Murder

Gosha is indeed not just a maker of samurai or yakuza films. Perhaps he can be seen as bridging the gap between the male-centered chanbara of Akira Kurosawa (a director he admired, although he felt Kurosawa’s films lacked sensuality) and Kenji Mizoguchi’s jidai geki narratives of women struggling against male oppression. He is, as Kazuyoshi Okuyama puts it, a painter of dark passions in the hearts of alienated humans, with a longing for the ritualized mores of marginalized social groups. Maybe Gosha was "a man of the past", as some critics pointed out, but he also understood that Japan’s future society could not fully bloom again without keeping something of the country’s true popular spirit and liveliness, and cherishing human warmth.

[Special thanks to Seiichi Sakai, who told me so many great things about Hideo Gosha – RG]

Robin Gatto is the author of the upcoming French-language Hideo Gosha biography Hideo Gosha, cinéaste sans maître, due to be published in 2014 by Lettmotif.