The V-Cinema Notebook, Part 1

- published

- 22 February 2014

The Japanese film, art and industry. The monumental status of Richie and Anderson’s pioneering book of that name, first published in 1959, makes it all the more peculiar that our subsequent chronicling of Japanese film history has leaned heavily toward the art, all but ignoring the structure and workings of the industry that generated it.

The Toei V-Cinema logo

We declared the 1950s a ‘Golden Age’ of Japanese cinema on the basis of a handful of A-list film directors and the awards their films won in Europe, while our understanding of the actual circumstances of their production (not of the individual films, but of the surrounding production model whose unsung popular commercial successes paid for the limitless means the studio heads put at the A-listers’ disposal) is limited to a statistic about record audience attendance.

Which aficionados of ‘classical’ Japanese cinema are aware of what transpired on the Toho or the Shochiku studio lots once one strayed off a Kurosawa or Ozu film set? Let alone the goings-on at such purveyors of more populist fare as Shintoho or Second Toei.

Recent years have seen an increasing awareness of these omissions among scholars of Japan’s cinema history. Daisuke Miyao’s investigation of how lighting and cinematography both reflected and shaped industry practices in the early days of commercial filmmaking in Japan, in his book The Aesthetics of Shadow, admirably steers us along unbeaten paths and away from the commonly (or rigidly) practiced auteurist approach. Likewise Jasper Sharp’s Behind the Pink Curtain is a history of far more than just its main topic of cinematic erotica, while Mark Schilling’s No Borders, No Limits conclusively demonstrated that Seijun Suzuki can only be considered a maverick if one knows nothing at all about the countless stylish actioners churned out on a weekly basis by the Nikkatsu studio during the 1960s.

When it comes to a more recent era in Japanese film, one we can roughly define as the 1990s, we are arguably dealing with a far more diverse and vibrant film scene than conveyed by an offhand but oft-repeated description like “entrenchment” or a statistic showing a record low in audience attendance. Granted, historiography tends to be longsighted and drawing conclusions about a time period whose reverberations are still being felt in the present time can be considered rash. Being a pioneer is not always the best position to be in: Mark Schilling’s book Contemporary Japanese Film, published before the decade had even ended, could be said to miss as many important names and developments of the 1990s as it covers.

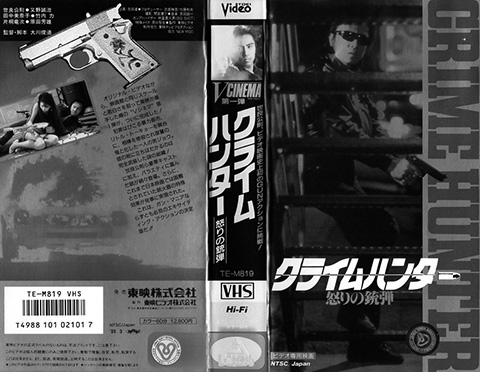

One of those important – one could argue epoch-making – developments is straight-to-video filmmaking, which took off during the in many ways pivotal year 1989 with Crime Hunter, the first entry in Toei’s V-Cinema line-up. Anyone with even a cursory interest in recent Japanese cinema will be familiar with such names as Takashi Miike, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Shinji Aoyama or Hideo Nakata, all of whom share a background making quickie genre movies destined for video store shelves which bypassed the theatrical circuit entirely.

Crime Hunter

While the straight-to-video model of distribution had already been in use for animation since the early 1980s it wasn’t until the runaway success of Toei’s first couple of V-Cinema releases that the format was adopted by other film companies as a means for producing and releasing live-action features. By the end of 1991, all the major players in film distribution, and a good number of minor ones too, had their own line-up of made-for-video product, under imprints like V-Feature (Nikkatsu), V-Movie (Japan Home Video) and V-Picture (VIP). None of these derivative trademarks stuck. In spite of all the blatant imitations and attempts to steal the crown, the original Toei brand name V-Cinema quickly came to refer to the entire straight-to-video phenomenon. (The other oft-used generic term ‘original video’ is almost exclusively used to refer to individual titles and not the industry as a whole, and also encompasses such audio-visual content as instructional videos and music releases - though this didn't stop distributor VAP from christening its straight-to-video line "Za Orijinaru Bideo")

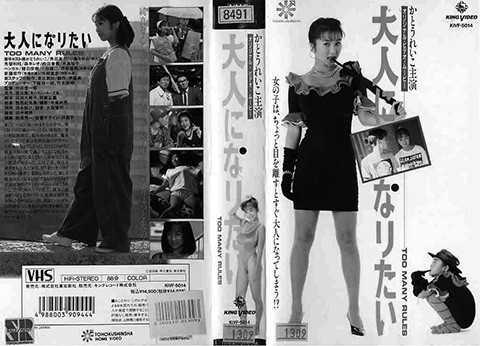

With the vast majority of video rental store memberships held by men, the target audience for V-cinema was distinctly male. The output corroborates this: action films, gangster films and sex romps (though not hardcore porn, which is produced and distributed by specialist outfits that exist outside of V-cinema’s confines) made up a large proportion of the product. The market was not uniquely male, however. Daiei chose to make its first foray into V-cinema with the romantic tragicomedy Asatte Dance (1991), while King Records’ freshman effort aimed for gender balance with the perky-yet-sexy Too Many Rules (Otona ni Naritai, 1991).

Too Many Rules

Already during the 1990s the influence of V-cinema could be felt outside of the domestic market at which it was originally strictly targeted. Eagle-eyed programmers for savvy events like the Rotterdam, Toronto and Vancouver International Film Festivals or the Brussels and Fantasia Fantastic Film Festivals began picking up on the industry and its more outstanding progeny in the latter half of the decade – not coincidentally the moment when some V-cinema productions began receiving token domestic theatrical releases in 35mm prints: as the reputation of made-for-video films declined into "a vulgar, artistically underwhelming product, churned out for quantity rather than quality"[ 1 ], releasing a film theatrically (usually a mere one week on a single screen in Tokyo or Osaka) allowed the distributor to proudly mention this feat on the video release packaging to help it stand out from the glut of cheaply-made video fare.

If, to provide a personal example, you were a loyal visitor of the Rotterdam film festival who had been exposed to the likes of Kitano and Tsukamoto in the early 90s, you could expand your burgeoning interest in contemporary Japanese cinema with for instance Rokuro Mochizuki’s Another Lonely Hitman (Shin Kanashiki Hittoman, 1995) and Shinji Aoyama’s Two Punks (Chinpira, 1996) – two films that are exemplary of V-cinema’s mid-90s ‘upgrade’ that paved the way for its international exposure. Similarly, many of those who attended the 1997 editions of Brussels, Fantasia or Toronto will have a vivid memory of when they caught Miike’s Fudoh: The New Generation (Gokudo Sengokushi Fudo, 1996) on the big screen – a film intended for the video shelves but blessed with an intrepid and idiosyncratic producer in the form of Yoshinori Chiba, who saw the potential of the film and its director. Chiba pestered his superiors at Gaga Communications to pay for a 35-mm blow-up and the rest is history.

Among the most influential of the early adopters was Tony Rayns, in his guises as programmer for Vancouver and London, and regular guest curator and advisor for Rotterdam. Rayns’s appreciation for the new Japanese genre cinema was rooted in Manny Farber’s ‘termite art’ tradition of holding aloft B-movie makers like Don Siegel and Joseph H. Lewis. He emphasised early on that the directors who worked in V-cinema were "not frustrated aesthetes forced to slum it in ‘disreputable’ genres"[ 2 ], as he wrote on Rokuro Mochizuki in the 1998 Rotterdam Film Festival catalogue. Instead he qualified them "supreme pragmatists", whose work consisted of "genre movies, made on a for-hire basis, with the generic elements left on auto-pilot while the director busies himself with form, rhythm, texture and the implications of the characters’ sexual pathologies."[ 3 ]

Another Lonely Hitman

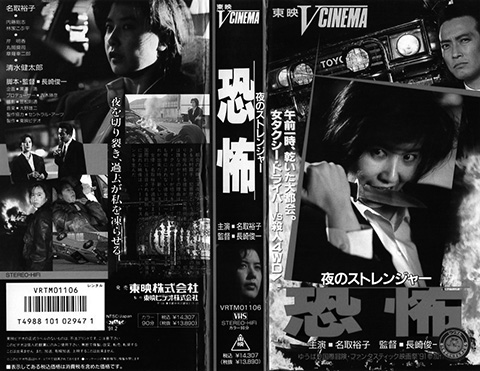

Despite its seemingly clear-cut formula, pinning V-cinema down to a definition is surprisingly hard to do. It was protean almost from its inception. It was not, as the sudden appearance of new talent might suggest, an industry hermetically sealed from the film world at large, as the supporting appearance of Yoshio Harada, an immediately recognisable veteran of everything from Nikkatsu youth movies to Shuji Terayama’s countercultural experiments, in Crime Hunter proves (Harada doesn’t even receive guest star billing, which suggests that V-cinema was from the beginning seen as ‘legitimate’ filmmaking). In spite of the key role of the kikakusha (‘planner’, a supervising producer credited with providing the basic creative concept of a film) it was not strictly a director-for-hire medium either: Shunichi Nagasaki’s Toei V-Cinema production Stranger (Yoru no Sutorenja Kyofu, 1991) was made from an original script by its director (and starred, again, an established actor in Yuko Natori). And as we’ve already seen, it also gradually outgrew the self-imposed confines of home viewing by giving certain films a big-screen outing, often accompanied by a slightly more comfortable budget, thus creating a profitable middle tier of commercial filmmaking that became vitally important for the progression of talent both behind and in front of the camera – progressing in some cases to Hollywood (Hideo Nakata, Takashi Shimizu) or the competitions of Cannes and Venice (Kurosawa, Miike, Aoyama).

Critical notice, however, did not keep step with V-cinema’s development. There was initial enthusiasm among observers in Japan, in particular from film critic Sadao Yamane, who was the first to draw parallels between these made-for-video features and the program pictures of old, like those made at Second Toei in the early 1960s which provided novice directors (including then unknowns Eiichi Kudo and Kinji Fukasaku) with a stepping stone toward feature filmmaking by helming 60-minute B-movies and episodes of serials.

Yamane also applauded the directing opportunities the new sector afforded to such established filmmakers as Teruo Ishii, Yasuharu Hasebe, Masaru Konuma and Akio Jissoji. Most of these men not coincidentally had their roots in previous models of production-line filmmaking: Ishii hailed from Shintoho, Hasebe started out directing Nikkatsu action pictures, Konuma rose from the ranks of Nikkatsu Roman Porno (which is comparable to Toei V-Cinema as an effort to ensure a company’s survival in troubled times by relying on low-budget genre fare, thereby offering opportunities for fledgling talent on both sides of the camera), while Jissoji came from television, where he provided many of the most interesting ingredients of the Ultraman series. The aforementioned Eiichi Kudo too helmed several straight-to-video titles for Toei in the early 90s. His 1998 yakuza film A Tale of Scarfaces (Ando-gumi Gaiden Gunro no Keifu), furthermore, is a typical V-cinema-derived middle-tier production that stars video store mainstay Kiyoshi Nakajo. It went on to receive a theatrical release in France after a festival selection at the Viennale in Austria.

As its image declined, however, further critical notice of V-cinema was not forthcoming. With one exception: film critic Masaki Tanioka doggedly observed and chronicled V-cinema, its development and output throughout the decade and into the 2000s, gradually seeing himself marginalised from a film press that had entirely given up on covering V-cinema by the mid-90s and ending up publishing his articles in a magazine for truck drivers. His various books, however, are invaluable sources of information on the phenomenon.[ 4 ]

V-cinema’s invisibility in the critical (and academic) discourse has, as Alex Zahlten suggests[ 5 ], "more to do with the inability of omnipresent auteur theory to cope with [V-cinema] than with a deficit in overall relevance." He adds: "In one of the most reductively business oriented sections of the Japanese film industry, a highly casualized labor system leaves little space for an auteur mentality on the side of either the producer or the spectator. The raw goods on offer seem reduced to sex and violence, and the often garish jacket covers reinforce this image. This does not appear significantly different from much of the films of the 1960s and 1970s, but these goods are stripped of the stylishness and budgets even a dying studio system could offer. Nevertheless, a distinct difference exists between the films and their marketing. Rarely is V-Cinema as vulgar, mind-numbingly simplistic or uncompromisingly sensational as it advertises itself."

Nor is it quite as anti-artistic in nature as Zahlten describes it. The example of Shunichi Nagasaki’s film Stranger proves that there was room for auteur-driven projects. "It was a project that I brought to Toei. While I was writing it, I felt it could work as V-cinema," Nagasaki remembers. "Toei V-Cinema had momentum at the time. If a project had a certain degree of action and suspense, then a project with a female protagonist could get made even if it didn’t contain any sexual scenes."[ 6 ]

Stranger

The producers themselves were not so crass that they didn’t hold artistic ambitions amid the everyday reality of modest budget levels, as Shinji Aoyama experienced. Aoyama’s first two films as director were released directly on video: the sex comedy Not in the Textbook! (Kyokasho ni Nai!, 1995) and the action film A Cop, a Bitch and a Killer (Waga Mune ni Kyoki Ari, 1996). After the art house production Helpless (1995) had formed his international festival breakthrough, he delivered a string of middle-tier genre productions: "My films An Obsession, Wild Life, Shady Grove and Embalming had budgets that weren’t very different from V-cinema productions, so they could be counted as V-cinema. [...] What I think happened was that their producers had the ambition to make ‘films’ and not V-cinema. They had a desire to make films, so they turned those projects into Shinji Aoyama films in order to release them in theaters."[ 7 ]

Had V-cinema indeed been entirely devoid of artistic sensibility then its merit would be that of a quaint, out-dated production model, historically a mere footnote at best. Instead it brought forth a number of filmmakers that would go on to define Japanese cinema on the world stage. "It’s been very valuable for me to have the experience of making program pictures," said Kiyoshi Kurosawa in 2001 (note his referring to V-cinema as "program pictures"). "Generally in that type of production environment, the subject and the story are already fixed. Also, you recreate the same type of film several times with only a slight difference. When the studio system still existed, many directors went through that experience. Today there is only V-cinema that can give you a similar experience. For me, compared to before the time I started working in V-cinema, I came to handle the subjects as well as the technical aspects of my films better and with more flexibility."[ 8 ]

Shinji Aoyama’s feelings about his V-cinema experiences echo Kurosawa’s: "It was like making a program picture, almost like the young filmmakers that emerged making pink films or Nikkatsu Roman Porno. I would phrase them as my ‘practice pieces’, which I got to experiment and learn from. [...] I did whatever I wanted as a director, I could explore what I could do within the realms of genre filmmaking. It’s not literary or great art, but still... I’m actually kind of sad that I don’t get offers to make those kinds of films anymore."[ 9 ]

To be continued

References

- [ 1 ]. Zahlten, Alex, The Role of Genre in Film from Japan: Transformations 1960s-2000s. Dissertation. Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg University, 2007

- [ 2 ]. Rayns, Tony, “Mochizuki Rokuro: A Supreme Pragmatist”, Catalogue 27th International Film Festival Rotterdam. Rotterdam: IFFR, 1998, pp. 230-235

- [ 3 ]. Rayns, Tony, “This Gun For Hire”, Sight and Sound, May 2000, pp. 30-32

- [ 4 ]. In particular: Tanioka, Masaki, V shinema damashi nisenbon no doshaburi wo itsukushimi. Tokyo: Yotsuya Round, 1999

- [ 5 ]. Zahlten, The Role of Genre in Film from Japan. Zahlten’s unpublished dissertation gives ample attention to V-cinema as one of three case studies of what he terms “industrial genres” (the other two are pink film and Kadokawa Film). It is one of the few, and so far certainly the most detailed, pieces of literature on V-cinema in any language beside Japanese.

- [ 6 ]. Interview with Shunichi Nagasaki by the author.

- [ 7 ]. Interview with Shinji Aoyama by the author.

- [ 8 ]. Mes, Tom and Jasper Sharp, The Midnight Eye Guide to New Japanese Film. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2004

- [ 9 ]. Interview Aoyama, see note 7.