Crime Hunter

- Year

- 1989

- Original title

- Kuraimuhanta Ikari no Judan

- Japanese title

- クライムハンター 怒りの銃弾

- Alternative title

- Crimehunter – Bullet of Fury

- Director

- Cast

- Running time

- 60 minutes

- Published

- 7 February 2014

by Tom Mes

Toei’s decision in 1989 to begin releasing feature films directly on video, entirely bypassing the ailing theatrical circuit, proved instantly successful. Its first straight-to-video live action film, Crime Hunter, was a profitable venture that provided a number of templates for a phenomenon that would profoundly mark the Japanese film industry over the decade that followed: V-cinema.

Contrary to what has been reported elsewhere (including by myself), the decision to release Crime Hunter directly onto home video formats was no lucky accident or last-ditch attempt to wring some yen out of a failed theatrical effort, but instead formed the first step in a carefully planned business strategy on the part of Toei Video. The mastermind behind it, a producer by the name of Tatsu Yoshida, had allegedly been frequenting video rental stores, where he saw young customers renting up to five tapes at a time. Asked how they could watch so many movies in a short time, the reply was: "By fast-forwarding." Having already received the screenplay for Crime Hunter from TV scribe Toshimichi Okawa, Yoshida aimed to launch the project for the video market as "a film that would not be fast-forwarded."

A number of historians, the few that have given V-cinema more than the most casual glance, have noted that the one-hour running time that resulted from Yoshida’s chosen strategy may have been based on a number of precedents. Alex Zahlten has pointed to the similar format of the pink film, while the venerable Japanese film critic Sadao Yamane, as early as the start of the 1990s, drew parallels with the program pictures of the 1950s and 60s, in particular those manufactured at Second Toei (Daini Toei, also ‘New Toei’), which produced a string of genre movies of around sixty minutes in length that were meant as supporting halves of theatrical double bills and formed a testing ground for fledgling filmmakers and stars (including Kinji Fukasaku and Shinichi ‘Sonny’ Chiba in the two Wandering Detective / Furaibo Tantei films they made together at Second Toei in 1961 before embarking on their feature film careers).

Crime Hunter’s restricted running time inevitably resulted in a good amount of narrative condensation. The focus is on action and the build-up toward it and even the action scenes themselves are frequently condensed further into montage sequences. Dialogue scenes exist only to deliver essential exposition, while character development is limited to mood swings that are usually expressed not through acting but formally, as expressionistic visual mood pieces.

This makes Crime Hunter, in a sense, pure action cinema, kinetic spectacle for its own sake – a procession of shoot-outs, car chases and explosions, situated in their most archetypal settings: harbour docks, night-time streets, nightclubs and warehouses. The film firmly belongs in the pre-John Woo era, however – its bandana-sporting alpha-male posturing and lack of irony place it more squarely under the influence of Stallone and Schwarzenegger. The cosmetic addition of Minako Tanaka as the feisty nun-turned-miniskirted sidekick Lily may serve as titillation for the male target audience, to the film’s stoic hero Masanori Sera (playing a traumatized cop named Joe, naturally) love takes a firm backseat to male camaraderie under fire, as he joins forces with his former nemesis, a fugitive named Bruce (Matano), for the climactic warehouse showdown against the nefarious kingpin who killed Joe’s original partner. (The partner’s brief appearance in the opening scene is notable for being played by the future king of the genre, Riki Takeuchi.)

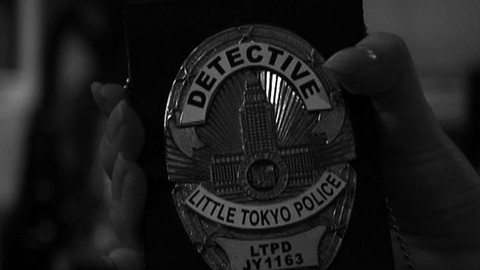

More interesting than the cookie-cutter plot is the film’s intentional blurring of national identity. Joe is an officer in the "Little Tokyo" police department and drives an American patrol car through a space populated largely by non-Asian extras. These attempts to make Crime Hunter different from the image of Japanese films (which at the time were seen as, in producer Tatsu Yoshida’s words, “too explanatory, so they have no speed”) are unintentionally ironic, as it places the film in the very Japanese tradition of the mukokuseki (no-nationality or borderless) action film as epitomised by the Nikkatsu potboilers of the 1960s.

Toei would continue to fall back on this trick in the early years of its V-cinema endeavours, expanding it to brief sojourns into overseas co-production with the US for its V-America label (which included the likes of American Yakuza, starring Viggo Mortensen) and Australia for the V-World imprint (the thrillers Crimebroker, starring Jacqueline Bisset, and Seventh Floor, with Brooke Shields). As unsatisfying as these concoctions were, and as indicative of the fact that bigger is not always better, even more ill-advised was the attempt at rebranding Ryo Ishibashi as a modern-day Cary Grant by dropping him into an indigestible hotchpotch of international spies, foreign mob assassins and returnee expats in Pinocchio: A Man Without Nationality (Chi no Shuseki Mukokuseki no Otoko, 1998), Toei’s dismal attempt at marking up V-cinema by making a mukokuseki action film for mass audiences, directed by a man who was otherwise one of the more notable directors to emerge from the V-cinema arena, Rokuro Mochizuki.

Its history and execution (and how closely these two factors relate) make Crime Hunter a definite curio that, thanks to giving the Japanese film industry a much-needed shot in the arm by kick-starting the V-cinema movement, holds undeniable historical value. Judged purely on its own merits, it comes across as cheesy and dated, certainly, but is no less enjoyable for it. Its by-the-numbers narrative and rigid adherence to genre archetypes are never less than effective, while the brief running time means that Crime Hunter does indeed speed along at a brisk pace and never grows stale, thus delivering precisely what it promises – which cannot be said for the vast majority of the hundreds of straight-to-video productions that followed in its wake.