Inuhiko Yomota

- Published

- 5 February 2009

by Rea Amit

In Japan, Professor Inuhiko Yomota, known to many as simply as Yomota Sensei, needs little introduction. Unfortunately, with virtually all of his important studies as yet untranslated, abroad he is known chiefly by those fortunate enough to read Japanese. The aim of this interview is to shed light on one of the most important figures in contemporary Japanese film criticism, and, quite possibly, one of the most important Japanese film historians ever.

Born in 1953, Professor Yomota is a unique figure in the world of Japanese film criticism. He made his first steps as a scholar right after graduating from the University of Tokyo with a PhD in both Korean and Italian studies, two disciplines that didn't exist at this institution at the time (and indeed still don't). While a student, Yomota had a part-time job assisting the editing of hand-written manuscripts by Kenzaburo Oe, recipient of the 1994 Nobel Prize for Literature. Immediately after graduation, he started working for several television networks as a film critic before finally receiving a post at Meiji Gakuin University in 1990, where he now serves as a Professor of Film Studies. He has also worked as a visiting professor in several countries, including Korea, Croatia, Italy, and Israel.

Among his publications we find not just cinema (Japanese, Asian, and Western), but also literature, music, manga, and even cooking. However, Yomota's devotion to film history and culture is obvious; he started focusing on cinema while still an undergraduate, writing for the magazines "Shinemagura" and "GS - Tanoshii Chishiki", in which he joined hands with such notables as the theorist Akira Asada.

Rea Amit met up with Professor Yomota in October 2008 for a general conversation about his sizeable body of work, just in time to celebrate his newest title, his 100th to date (!) since he was first published over two decades ago.

Your work spreads into many different disciplines - music (Schoenberg, Bach, and Toru Takemitsu, whom you knew personally), theatre (Artaud, Shuji Terayama), literature (Paul Bowles, Kenji Nakagami) - and you even wrote several books on different countries and their cultures (Korea, Italy, Morocco), but still film seems to be your main interest, why is that?

There are two possible answers to that question. The first is simply that I've liked films ever since I was at elementary school. Back then I used to watch many Japanese genre films, like action, kaiju eiga such as Godzilla and Mothra, westerns made in Japan, samurai flicks, chanbara, etc. Through junior high and high school I was an avid movie-goer, and I still am. Of course, during this period till nowadays my interest in films and generally in the cinema has changed, and since university has naturally become more academic. It was at university that I started writing for several magazines about the latest releases of the day, about people like Wim Wenders, Fassbinder, Godard, Jim Jarmusch, etc. I was proud of knowing the best and latest world films and being the first to introduce them to Japanese readers.

The second answer might seem to somewhat contradict the first, in that I'm not actually a real or proper film historian or critic at all, since films are, as you mentioned before, just one aspect or topic among my various interests. My focus in writing has always been the same kind of issues that I find sometimes in manga, sometime in literature, but more often, almost randomly, in film. Take for example the time I wrote about Kenji Nakagami; I was actually interested in my generation's representation of discrimination in fiction, and Nagakami, who was also a drinking buddy in Shinjuku, was taken merely as a case study. I didn't go on looking around him, at other people he used to hang out with, like Ryu Murakami for instance, or to push my studies forward by writing about Haruki Murakami, since it was merely this general idea, and not a specific genre, that interested me in the first place. And the problem of discrimination still haunts me to this day, and I keep on writing about it through other subjects, such as the work of Edward Said and so on.

Yes, you might be more comfortable with the title "cultural critic", though it's still very obvious that your work on film extends much further than on any other cultural discipline.

That is correct, though it is basically because cinema highlights so many different issues; ethnicity, linguistics, and so on. And besides, we are now already in the 21st century, but you and I are both people of the 20th century. What is it, after all, that makes the 20th century unique to human history? Different people will answer differently, but for me there are three main key points: the rise of fascism, psychoanalysis's notion of the unconsciousness, and the third is, of course, film. While film wasn't actually invented in the 20th century, its peak in importance was most definitely during this time, and it's now already over. Even though we still have films, we also now have DVDs, the internet and many other different types of media, so the importance of film, especially as it was conceived in the last century, as something to be seen in movie theaters, is gradually diminishing. However, all three things have something in common: that is human fascination, image-based or imaginary thinking, and iconic presentations (propaganda etc). Another reason for me to focus on film to the extent that I do is that cinema, more than any other medium, is a vast and all-encompassing field. For example, one could discuss the music of Schoenberg in film, but it is not possible to do it the other way round. Eventually all these issues I'm interested in find form inside the cinematic world.

I have a pretty clear idea of how you might answer my next question, but I would like to hear it from you anyway. Beside your obviously unique ideology, or philosophy if you will, what makes your work on film different from other Japanese critics today?

Yes, indeed, this is very easy to answer: I'm a "minority". As 90% of the global film industry's financial activity is based in Hollywood, Japanese critics tend to focus on American films. However, I take a clear distance from Hollywood, from its ideology or suchlike. This alone puts me at a completely different starting point from most Japanese critics today.

It seems as if you have a special interest in minorities, or with marginal cinematic phenomena, like Okinawa, women, pink films, and numerous other topics.

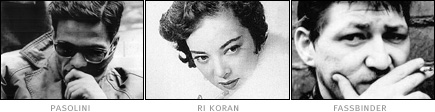

Yes, you are right, but not just in Japanese film and actually not just in film either. I'm interested in the actual social phenomena as of themselves, which, as I see it, are portrayed very clearly in many films. This is a moral stance. In the counter-cultural sphere, as a stand against all wrongdoing, you have a few people, or in cinema just a few directors. We have in Japan, for example, Oshima, in Germany, Fassbinder and in Italy, Pasolini. These three, without any doubt, belonged to a "minority" in the societies in which they worked, and were considered somewhat "strange" or sometimes even worse - as in the case of Oshima, who was regarded also as something of a "national shame". So, these people were courageous, and it is this courageousness that I would like to alert my readers to. Not just in Japan but also in nearby China, people like Zhang Yimou, whose films were banned at first from public screening following the notion they have in China to "never show one's dirty laundry to a stranger". I really respect people like that and find them fascinating. For instance, I named three directors - Oshima, Fassbinder and Pasolini - all of whom I have already written many things about before. I've translated some of Pasolini's writings into Japanese, and am now in the midst of writing a new book on Oshima. What do you see in common between them?

Well I wasn't prepared to be asked any questions, but I know that the homosexual issue played a major roll in both Pasolini's and Fassbinder's lives, and Oshima made Gohatto...

No, that's not what I had in mind. It's that all three directors were born under the Axis fascist regimes in their respective countries, and worked in the post-Axis environment created after World War 2. The three struggled to talk about everything the previous generation didn't want to or didn't dare talk about. It is, in a way, their way of either compensating or even mourning all the misdeeds and atrocities committed by the previous generation. I don't know for sure whether or not any of these directors ever read Walter Benjamin, but their work in a historical context becomes very clear from his theoretical point of view. You see, this is a way of regarding film in a historical, critical and also ideological context. This is also something I generally find very hard to do in Japan. That is, while in China there is no freedom of press, if someone there dares to print something outrageous or scandalous, people will quickly make a huge fuss about it and many will try to read it, but in Japan, where anyone can go on publishing whatever they want to, no one pays any attention anymore to what is actually written. This is also, I believe, what puts me on a completely different ground as a critic, as both the films I choose to discuss and the way I write about them are completely different from what people here usually want to read.

What about foreigners who write about Japanese cinema from an outsider's point of view? Are you aware of any of their publications?

Take Donald Richie, for example. I consider him as something akin to a grandfather, as someone two generations above me, in writing I mean. I truly respect his work. However, I eventually had this tendency to stop taking his writing too seriously, just like someone might find their own grandfather respectable and wise, but also somewhat irrelevant to their generation. I think that people tend to rebel against their parents, but also just to disregard their grandparents. But again, generally I really appreciate what Richie did for Japanese cinema, for introducing people like Kurosawa, Ozu and Mizoguchi to the world and for having the courage to come to Japan just after the war when it wasn't anything like it is today.

How about people besides Richie?

As for other critics and writers, it's really hard for me to say. There are too many. And too many fundamentally different perspectives; psychoanalysis, Marxist, gender... And there are also formalists, deconstructionists, and so on. But what I would say is that what I find crucial for writers is to know your subject very well - the historical context, the culture and the language too, for me plays an important role in my own study of film. When I watch a Theo Angelopoulos film, it's not the same thing as when a Greek person watches it. This is the fundamental basis upon which my writing is completely different from those who write about Japanese film from the "outside point of view". It's the fine details that are lost in the eyes of an outsider, and I take every detail to be very important. When someone watches a Mizoguchi film for example, sometimes it is very important to know that same story they're seeing on screen was first known as a kabuki play, or to know how different the roles the actors are performing in it are from their other plays or movies.

You just mentioned Mizoguchi, and I believe that it would be very difficult to classify him as a "minor" director, and yet you have published a wide range of research concerning him and his work. What brought you to write about him in the first place?

Well you see Mizoguchi is a very complex subject to write about...

Would you say that Kurosawa, for example, is any less complex?

(Laughs) You're teasing me, huh! Of course this is not what I mean. First you must realize that about half of Mizoguchi's films are lost, and so we're missing the total sum of his work. In Kurosawa's case nothing was lost. Moreover, Kurosawa also wrote and explained his intentions or his philosophy, while in Mizoguchi's case we have no idea what brought him to make films the way he did. What's more, Kurosawa was an intellectual, and Mizoguchi was far from being one. He left no explanations or comments, so we must rely on speculation and interpretation. This is what makes him so complex. Besides, I consider the most important different feature between these two directors to be that while Kurosawa was a man of action, Mizoguchi was basically interested in women. Male-female relationships are for me the most difficult topic to deal with. As a matter of fact, when I first thought about writing about him I immediately realized how hard this was, so prior to the actual writing I organized a huge conference, to which I invited important figures such as Dudley Andrew from Yale.

If I look again at your work so far and your latest book "Nihon no Marano Bungaku" (trans: 'The Marranos of Japanese Literature'), for which you lately received the prestigious Kuwabara Prize (among whose previous winners is Haruki Murakami), I see one topic that comes back again and again - the actress Ri Koran, a.k.a. Yoshiko Yamaguchi. I find it particularly interesting because Ian Buruma has also written about her in his new book The China Lover. What can you tell me about that?

I didn't know about Ian Buruma's newest publication, but indeed he came to visit me a while back and asked me many questions about her. He also seemed to have read some of my writing in great detail. What I find very interesting in Ri Koran is the fact that she changed sides, from the fascist actress that she was, pretending to be Chinese for the Japanese propaganda machine, to, in what I consider as an apologetic move, the liberal or humanistic side. She never tried to hide the things she had done in China. On the contrary, she spoke about it widely and openly. In Japan this sort of behavior is extremely rare. Japanese try to hide the darker parts of their life history, as much nowadays as then. The Nanking Massacre and other incidents from World War Two are not taught at school, which means they're being hidden. Ri Koran has spoken openly about her misdemeanors against the Chinese people. She wrote about it herself and she also helped others to write about it.

There is also of course this aspect of her in the television show called "Sanji no anata" (trans. 'You At 3 O'Clock' - the show ran from April 1969 to March 1974).

Yes, this is a very important point. Ri Koran was born in Manchuria, as an occupier of a land that wasn't hers. It was this, and I am certain it wasn't anti-semitism like some might suspect, that drove her to Palestine with a great compassion towards the people in the occupied territories. When she was young in Manchuria she saw how the Japanese treated the locals - Manchurians, Koreans and Chinese - as "second class" citizens, and that, I believe, is what made her pay much more attention to this sort of injustice, when she visited Israel and found there Israel's own "second class", the Israeli Arabs.

She is without any doubt a remarkable radical. A decade ago you named one of your books "The Radical Consciousness of Japanese Cinema" ('Nihon Eiga no Radikaru na Ishiki'). While it dealt with completely different aspects of radicalism, we do find other figures from the generation after Ri Koran who were at least as radical, like Koji Wakamatsu, Masao Adachi and Nagisa Oshima. Can you please explain the various differences in this "radical consciousness"?

Wakamatsu told me once, "Oshima is my friend, but if you ask about our films, well, Oshima's are for intellectuals and for them only to watch. Stupid people (baka) don't and can't get them. Mine, however, are easy for both intellectuals and stupid people alike." Wakamatsu is not an intellectual. He is a common man (shomin). And even though he is not a yakuza, he holds the same popular morality they do - helping the weak, hating public or government officials (yakunin). If someone is being persecuted, for no matter what reason, they must be helped. To this goal, all means and actions are considered legitimate, just like with the yakuza. Concerning the Palestinian issue for example, Wakamatsu didn't know anything about it at the time. He just thought that while everyone was focusing on Vietnam, he could make some money filming the Palestinian struggle. It was only after he met some of them in Lebanon that he grasped the reality of their actual situation and started feeling compassion towards them

So you are implying that he might not be a real radical?

He is, but one who holds a yakuza-like moral code as the basis for his radicalism, namely that of the jingi, the famous yakuza code of honor. He is not interested in power but in helping the weak. So, for example, if Wakamatsu was working in a different environment, like let's say the late 30s in Germany, he would then, without any doubt, join the Jewish side against the Nazis. And we actually know of certain other Japanese that helped save Jews at that time without knowing anything about the Jewish people or their religion, simply because they were following this sort of common moral code.

I see. Well, what in this case can you say about the other radicals you wrote about in your book, people like Shinji Aoyama, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Sogo Ishii, Takeshi Kitano, Shinya Tsukamoto...

(interrupts) Shin-chan! I had high expectations of Shinya Tsukamoto in the past but now... well, we'll have to wait for Nightmare Detective 2 before we can say anything...

Yes, to me they seem currently to be standing on a completely different ground than the radical filmmakers that you described before. What do you think about this?

First, as you said, this book came out a decade ago. It was true then, but now indeed there's a different feeling about these filmmakers. Kitano was just a beginner back then, but then he became a "big name". At the time he seemed to be concerned with the presentation of violence, but now he has become somewhat humanistic. People change. What might be interesting in this context is maybe Takashi Miike, right? And also maybe J-horror - Hideo Nakata, Takashi Shimizu and others. When you look at the people I discussed in that book, you can see that maybe half of them at that time had been involved, even if only partially, in horror. I think that ghosts and horror films in general are a very important issue. It has to do with the unconscious, and also the fact that ghosts are almost always victims.

Especially in Japanese literature and film.

Yes, American horror is mainly monster horror, a monster that society tries to exclude, while Asian horror, Japanese, Thai or Malaysian horror, is that of ghosts. Ghosts are victims of the past, women who were raped, discriminated people, or other victims of society who refuse to disappear quietly.

I know that one of the projects you are working on at the moment is on Asian horror cinema, and that you've just come back from a long stay in Thailand, and next week you're leaving for Malaysia. However, let's put that aside for now and maybe, as your books have yet to be translated, could you say which one you would most like to see published in English?

I usually write about subjects that are not familiar enough to interest English-language speakers so, though I would like to see my Kenji Nakagami book translated, I'm afraid it wouldn't make sense to translate it, right? Probably it would be quite interesting to translate my Kawaii-ron [essay on the concept of kawaii, or "cuteness']. As for others, well [long pause while he checks the list of his publications], I guess I would like to see Haisukuru 1968 ('High-school 1968') in other languages since it could be interesting for many people to compare their high-school experiences with a Japanese person's from the late 60s.

What do you think of Japanese contemporary film?

Basically I think that it is in desperate need of a good producer. We haven't had one for quite some time now.

Are there any bright points?

I recently saw Kunitoshi Manda's The Kiss (Seppun) and was highly moved by it. I think it's a fantastic film. As for the future, it's hard to predict. Let's just wait and see what comes along.

I would like to end with a different topic. You've worked hard to establish the importance of several film directors, most notably Wakamatsu of course, but also Kiju Yoshida, Kazuo Hara and Toshio Matsumoto. But what do you actually like to watch, do you have any all-time favorite cinematic figure?

That would be Lulu of course! I've been fascinated by Louise Brooks ever since I first laid eyes on her. I've actually written about her too, and even translated her autobiography into Japanese.

[Note 1: Louise Brooks is very typical Yomota motif - as a lost object of fascination, and especially for her leading role in Pabst's Pandora's Box (1929), which has been seen as anticipating the horrors of fascism in its exploration of human unconscious desires.]

[Note 2: As mentioned, as yet little of Professor Inuhiko Yomota's works has been translated into English, although his history of Japanese cinema has been translated into German as Im Reich der Sinne - 100 Jahre japanischer Film.]