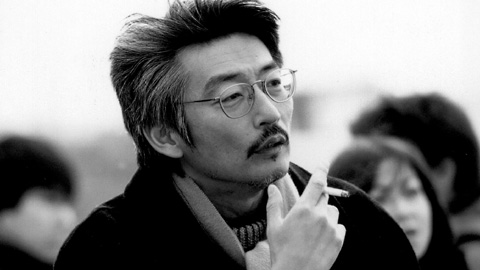

Shunichi Nagasaki

- Published

- 8 June 2006

by Chuck Stephens, Tom Mes

Earlier this year, one of the most consistently overlooked directors in Japan was finally given his due respect when the Rotterdam Film Festival showed a thirteen-film retrospective of the work of Shunichi Nagasaki. The ever-enterprising and pioneering festival even opened its doors with a screening of the director's latest, a remake cum sequel cum documentary of his 1982 film Heart, Beating in the Dark (Yamiutsu Shinzo). One of the most daring and original films to come out of Japan this year, Heart, Beating in the Dark - New Version, as it is officially called, revisits the original 8mm feature that formed one of the touchstones of the generation of independent experimentalists that rejuvenated Japanese cinema. In Rotterdam, Midnight Eye's Tom Mes and special guest Chuck Stephens spoke at length to Shunichi Nagasaki about his life and career, from his early days as a rock music fan to his most recent film.

Why a remake of Heart, Beating in the Dark?

The producer Shiro Sasaki of Office Shirous mentioned the idea of a remake several times to me over the years. At first I thought "It's a finished film, it's in the past and there's no point in doing a remake." Then one day I wondered what would happen if I looked at young people in that situation today. It would probably turn into a very different film, since I'm older now. Then I began to become more favourable toward the idea. But before the film actually came about, a lot of time passed and a lot of things happened. There was a script, but I felt something was lacking, I wasn't happy with it. Then we came up with the idea of having the lead actors from the original version appear in the film in some kind of documentary style. But they also weren't quite happy with that idea and felt that it still needed something more. So other ideas came up, me wanting to put in my own ideas, the actors wanting to reflect on their own roles and on how things change in life. How we felt about filmmaking, and about life in general, all these things ended up in the film as well. But it took a long time before they all came together.

What music did you listen to in your youth? I know you are from Yokosuka, which would suggest the influence of American music through the U.S. naval base there.

I wasn't actually born in Yokosuka, but close by, in a small town near Yokohama, an industrial town. If we talk about my younger days, then we're talking around 1970, so I was listening to the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, those kinds of bands. Once I started making films I was listening to all kinds of music. As far as the influence of music on my films is concerned, it's not so much that I wanted to use certain titles or references to rock music because I loved certain bands or songs. It's more like the case of The Lonely Hearts Club Band in September: after the film was made it brought back memories of Lonely Hearts Club Band by The Beatles. So it's not that the music inspires the film, it's more that the film gave me an image that reminded me of the Beatles song.

Also, it's not the Beatles's music as such, it was more about the way the film's characters gather, which is more or less like the way members of a band would gather. Everyone has their own role: one does vocals, another guitar, a third plays drums. Another thing in this case is the way the sound of the words "Lonely Hearts Club" seemed to fit the atmosphere and the imagery of the film.

This is often the case when I make my films. For every film there seems to be some sort of music that comes to mind, that fits the atmosphere of the film. In the case of Some Kinda Love it was Miles Davis. There's no direct relation between the content of the film and the music of Miles Davis, but when I was making the film, the whole of the images and the atmosphere connected with the music of Miles Davis, particularly his electric period.

The Lonely Hearts Club Band in September (Kugatsu no Jodan Kurabu Bando) is one of the pivotal films in your career. You made that film with the Art Theatre Guild. Could you tell us how it came about?

This was my only film with ATG. The head of the company at the time, Shiro Sasaki, was actively trying to finance films by younger directors. Back then it was especially hard for a young filmmaker to get his film financed and Sasaki wanted to give people like myself and Sogo Ishii, people who didn't have any experience as assistant director, a chance. He laid down the policy for doing this. The way it happened in the 1960s at ATG, when they produced films by Nagisa Oshima and Kiju Yoshida, was that the budget per film would be twenty million yen and that ATG would put up half of that amount and the director or his production company had to find the other half. Sasaki-san later quit ATG but I did several more films with him as producer, like Some Kinda Love, A Tender Place and the new version of Heart, Beating in the Dark. So we've been working together for a long time now.

Back when I was reconsidering my own films after a stay in the hospital, I made Heart, Beating in the Dark. I thought that ten million yen was a lot of money and that I could do a lot with an amount like that. Once I got to the set of course I realised that ten million yen is nothing. I realised the true meaning of 'low budget'. Sasaki-san also didn't originally come from the film world and he recently admitted to me that at the time he also had no idea of how little ten million yen was in the context of a film production. We both were very impressed with what we achieved with so little money.

You just mentioned your time in hospital. There was a serious motorcycle crash during the making of Lonely Hearts Club Band, which landed you and several other people in medical care for almost two years. How did the film change as a result of this?

Before the accident, when we started production, we were making the film without thinking too much. We were just enjoying ourselves. Very much like the bikers in the film are just enjoying themselves riding their bikes. But while I was in the hospital I had plenty of time to reflect on what I had been doing as a director and what kind of films I had been making. I had done these independent films as a student. What I realised is that up to that point I had been imitating films that I liked, and I felt that I should change that. In that sense the accident and the period of reflection afterward marked a very important change both in the content of my films and in the way I made my films. I've often said this, and it's really true, but the films after Lonely Hearts Club Band go in a very different direction, both concerning their content and the way the films are put together.

What were these films you tried to imitate?

As a high school student I wasn't really interested in films or filmmaking. When I went into a movie theater it was mainly to kill time. But one time I happened to watch the film Female Convict Scorpion (Joshu 701-Go: Sasori, dir: Shunya Ito, 1972), which is an action film from the Toei studio with a female protagonist, and I thought it was very, very interesting. From that moment on I began watching a lot of other Toei action films and Nikkatsu action films. I didn't have any equipment, but a friend of mine had an 8mm camera, so with that we started making films ourselves. It wasn't so much the film itself that intrigued me or got to me, but more what was depicted in the film, the feeling of freedom was what really impressed me and what I still remember most about it.

I couldn't help thinking of Sogo Ishii's Crazy Thunder Road while watching Lonely Hearts Club. Since they were made around the same time, is there any kind of relation between the two films or did you and Ishii communicate about the films?

I don't see Ishii much anymore, but in those days we did meet up from time to time. Of course, these films were made around the same time, but it's not that one film inspired the other. The phenomenon of bosozoku biker gangs was everywhere at the time: it was in the media, everyone talked about it. So that image of the bike gangs as a youth culture was really in the air. In that sense it's no coincidence that there were several films about this same subject.

I forgot to mention something important, which is that the person who did the lighting for Thunder Road was also the cameraman of Lonely Hearts Club, and his assistant also worked on both films.

Does that exchange have something to do with the fact that you were at the same university and working with people from that university?

We are the same age, but Ishii was one year lower than me. So in the school context we didn't have so much contact. It was outside school that were both involved in these joeikai, these screening meetings where we would both show our films.

If I compare the two films, I would say that Crazy Thunder Road is the explosion and Lonely Hearts Club Band is the aftermath.

I guess that's a valid interpretation. I did see Ishii's film, because it was released before mine was finished. Perhaps there was unconsciously some sort of influence that made me construct my film as a sort of follow-up to his.

In a less direct sense, this connects with the idea that a lot of your films are about what comes after some kind of crisis or some kind of traumatic experience, and how the characters cope with that experience. That continues right up until your most recent films.

I'm not really deliberately or consciously doing this, but I am interested in characters like that, who have to face the things that have gone wrong in their lives. I hadn't seen Lonely Hearts Club Band in a long time, but when I watched it again recently to work on the English subtitles, I was reminded of the fact that all these various elements of Lonely Hearts Club Band still return in my recent films.

In the early films that aftermath seemed to mostly have to do with the end of youth. Your early films have a sort of youthful energy to them, a kineticism that your later films don't show as often. It suggests rock 'n' roll, but the films' titles suggest something after rock 'n' roll, a sort of exhaustion with it. It's not just The Lonely Hearts Club Band, but it's in September, a sort of autumn of rock 'n' roll. Another title is Rock Requiem, or The Summer that Yuki Gave Up Rock Music.

At the time I was shooting Lonely Hearts Club Band, I felt there was this rock-like energy present. But at the same time, I also couldn't fully believe it. This probably has to do with my own personality, but as I was expressing this rock-like energy in my films, at the same time I tried to relate it to my own age, my own position in society and life, and to somehow connect it to that. For example, in Lonely Hearts Club Band again, the theme is "how do these young people go out into the world?" Today of course, being much older, I know the answer to this question, but at the time I was making these films, I was reflecting on those issues and those themes, and these reflections also found their way into the films themselves.

Not only for myself, but also for the crew and the cast, Lonely Hearts Club Band was a film about how we should face adulthood and how we should face becoming adult members of society. This is also something I realised only recently, and it was quite a strange sensation to realise it. At the time I wasn't aware of it. Other people have told me repeatedly that a recurring pattern in my films is that the characters have all lived some kind of intense experience - a crisis or an intense love affair - that made them feel really alive. But that they lived this before the film starts. So the films are actually about afterward, how they deal with the fact that this intense experience is over.

A lot of your films are very self-referential and self-reflective. Cameras appear in the films, there is use of 8mm footage as clearly being 8mm footage, and so on. Where does this come from?

I'm not really so seriously preoccupied with these matters. In the beginning I didn't really know how to show things I wanted to express and didn't know who I was going to show the film to. I had no clear ideas about these matters. I ended up thinking a lot about what it means to make films. On a number of occasions where I start thinking along these lines, I end up incorporating that in the film. So this reflection on what it means to make a film then becomes part of the film. But I repeat, it's not meant to be taken all that seriously.

There seems to be another break in your career with the thriller The Enchantment (Yuwakusha) in 1989. Do you yourself also look at the film this film in this way, as a change in your career?

I had done a few films with major production companies before The Enchantment, so I had had a chance to work with a real film crew and a more extensive cast than in the past. That actually gave me a chance to concentrate more on adding my own personal approach and my own personal elements to The Enchantment. Those previous films were a training ground for the experience of working with a bigger crew and cast, and with The Enchantment I could use that ability to focus more on what I really wanted to add to the film, personally. You could say that, in a way, it was a starting point, but at the same time I realised that it was not the direction I wanted to continue heading in. There was an ambiguity there: it felt like a new start, but there was also the realisation that this was not the way I should make films all the time. I had the feeling that human emotions, and those are what interests me the most as a filmmaker, could not be depicted fully and in a satisfactory way in a film like The Enchantment. So it was also a realisation that I had to change my ways once again.

Many of your films, The Enchantment included, contain strange, dreamlike scenes. Do you set out to insert such scenes from the moment you start developing a film and its story?

It differs from film to film. In the case of Dogs we had a script that was fully developed but we didn't have enough money to shoot it the way it was written. The art director Yohei Taneda had a big influence on this film. Normally he is used to working with bigger budgets, but he and I discussed for a long time how we should handle translating the story for the money we had. He came up with the option of showing things as if they were happening in a dream. He probably had a different definition in mind than I did, but it was the moment we decided to shoot the film in black and white. I then also discussed with the crew how we could create this dreamlike image and it was the cameraman who suggested that we shoot the scene in the woods the way we did: we follow her running, but the scene focuses on her thoughts drifting off and getting lost. So a lot of the times these kinds of scenes come about on set, in collaboration with other members of the crew.

How do you approach filming the city? Several films share that very dreamlike image of the city environment, filled with dark corners and fog. At the same time, a film like Stranger [Yoru no Sutorenja: Kyofu!, 1991] contains almost documentary-like shots of streetlife at night.

It depends on the film and what I try to achieve. With The Enchantment I wanted to have a very dreamlike atmosphere. I wanted to have the scenery outside look like it was shot inside a studio, as if it were artificial. But with Dogs and Stranger I was looking for a more real atmosphere, a feeling of proximity.

Stranger was an interesting film in that it was an urban paranoia/stalker film, which is quite a rare genre in Japan. In comparison to, say, New York, Tokyo and other Japanese cities are very well lit at night and there are hardly any dark corners for stalker types to hide.

Probably there hadn't been that many of these kinds of films at the time. What I wanted the heroine to feel was that there was a total stranger after her. It's not like the usual set-up, where somebody has done something and knows exactly why the others are after them. That may have been something quite new in Japanese cinema, that the heroine didn't know why she was being pursued. There was a more realistic feel to it. I didn't want it to be like in a film, but to give it the reality of the fear of being stalked or of someone trying to kill you. What I was also interested in, while making this story, is the fact that because she never knows who the stalker is, she never gets a good look at him, and so she is forced to confront herself.

Could you talk a little bit more about how that collaboration between you and Yohei Taneda works?

We've worked on four films together so far. He's used to working with big budgets and my films are very far from that, most of the time. Of course he brings in a lot of his artistic experience from other films, which benefits the films I make, but what I like about him is that he really comes to the point, he knows how to pin down what the film is about. He didn't work on The Enchantment, but he read the script, and immediately after he finished reading it, he said "This is a kind of ghost story." And for Dogs he said: "This film is like the heroine's dream." In one phrase he can capture what the film is about and that really helps me to work on it from there. The one phrase he uses becomes the base from which I can develop my ideas.

Would you say it's true that film as a way of investigating something, of searching for something, is a constant and a central concern in your work?

You're probably right. Things that I already understand aren't very interesting to me. Characters that make me wonder why they do the things they do are interesting to me. That tendency is probably there in the films. Another thing, maybe this is not related, but in the way I make films I have the same feeling. Already when I was making 8mm films, if a film became too 'film-like', this may be a strange way of putting it, I would automatically start looking for ways to change it. Even when I later made films with bigger budgets and larger crews, this happened. Normally, when you make an action film, the basics of it are obvious: you have a cameraman and a crew and they do what they do. Those are basic, standard procedures in the way films are made. But I always have my doubts: is it really okay to do it this way? Is this all there is? I'm always considering and thinking about whether we shouldn't try it a different way. A lot of films are made while taking these things for granted. This is very important to me.

I'd like to talk a bit about genre film. You say yourself that a lot of your films are genre films. In Japan there are a lot of opportunities to make genre films. Even if a lot of these come with certain restrictions, there is a certain degree of creative freedom for the director. A director can carve out a career for himself as a genre filmmaker in Japan and still find room in his work to gets things off his chest. But you've chosen to not take that route in your career. Why this wish to not follow that and keep a more independent direction?

I guess for me making genre films is not a simple matter. It's quite difficult in the sense that you have something that the producer demands, but there is also what I like to do. Somehow that relationship doesn't work very well. I always have the tendency to deviate from what the producer wants. I've told myself that it would be good to do these genre movies the way the producer wants and then I would have a lot of work, but somehow I always deviate from that.

To be more precise, it's not that I deliberately set out to deviate or upset the producer, but it's always when I see the finished film that I realise that I've done it again, once more I deviated from a producer's wishes.

But if I were a producer, I could easily imagine, for example, cutting a trailer for Lonely Hearts Club Band that makes the film look like a more or less standard biker action flick.

That film was a slightly different matter, since it was produced by ATG. Sasaki would actually try to encourage this kind of deviation.

You've shot films on many different formats. Do you have a favourite format?

When I look back, I notice that I've used all these formats over the course of my career, but it's not that I set out to try and use such a variety of formats. Usually it's dictated by the circumstances: the amount of money or the fact that a film is made for TV. But I try to approach this in a positive way: though I'm constrained to use a certain format, I try to see how I can employ it in a way that fits that particular film. I try to turn it into something positive.

Is there a theme or subject you still wish to cover in your films, but haven't had the chance to?

There are plenty of things I'd still like to tackle and do, but they're very vague. I don't keep a list of topics I want to cover. Usually how it goes is that something happens one day and this works as a trigger to get me working on something. One other big reason, also not unimportant, is that sometimes I do things simply to make a living.