The Anticipation of Freedom: Art Theatre Guild and Japanese Independent Cinema

- published

- 28 June 2004

Since the beginning of the 1990s, Japanese films have been very successful internationally at film festivals and have become an essential part of the worldwide movie/video/DVD/television market. Anime, which, of course, are a world of their own, have conquered TV channels and the hearts of children and adults alike and are now moving on to the big screen. More importantly, several directors, who started out in the 1990s (or, more precisely, after 1989), have come to the center of attention. At film festivals, there were the contemplative/theoretical works of Shinji Aoyama, Hirokazu Kore-eda, Naomi Kawase and Nobuhiro Suwa, in the cinemas (and among the fans) there was a little more action in the films of Takashi Miike, Shunji Iwai, Sabu, Shinya Tsukamoto and Isao Yukisada. Merely Takeshi Kitano is an exception: he is successful in both fields and is the only Japanese heavyweight in the international movie ring.

As the films of these directors were (and are) often presented as "Japanese Independent Cinema" and because Japanese films up to the 1980s have largely been ignored in the West, one might get the (erroneous) impression that independent cinema in Japan was a thing of 1990s. We have to ask ourselves, however, what "independent" is supposed to mean in the context of the Japanese film industry of that period. The term "independent", i. e. independent of the big studios, has become almost meaningless nowadays, at least on the production level. The studios Shochiku, Toei and Toho make very few in-house productions and participate in barely a dozen films as co-producers annually. More than 95% of all films are made outside the studios. If the term "independent" has any significance at all it is on the distribution level, but even here things are not that simple. In 2002 the three big studios distributed 45 films, including 13 anime (their main source of income), the remaining 203 films (including 98 pink eiga or sexploitation movies) had independent distributors and were shown in cinemas that do not belong to the studios which still play an important part in the distribution and exhibition of films. All of this goes to show that the meaning of "independence" in Japan is very different from the US, where the Hollywood studios still dominate the film industry, or Europe, where government subsidies form the basis for "independent" films, i. e. films that do not necessarily conform to mainstream tastes and that do not follow primarily commercial goals.

In Japan, unlike Europe, the film industry is not supported by government subsidies but is at the mercy of the "free market". That is why budgets are generally very low. Nevertheless many Japanese films are high-brow and "difficult" and do not conform to majority tastes but appeal to small minorities. This shows that despite unfavourable circumstances Japanese filmmakers are determined to stay true to their vision (and still make commercial films). And it also proves that they are capable of countering scanty means with creativity and original ideas.

Even with regard to differences of plot and style the distinction between "independent" and "mainstream" has lost its meaning, as the biggest differences are to be found within the field of independent productions themselves.

The 1980s saw the formation of several independent distribution and production companies as well as of so-called mini-theatres. This provided the basis for an alternative movie market and an increased diversity of film production. The starting point of this development was ATG, the Art Theatre Guild, which was established in 1961 as an independent distributor of foreign art films as well as Japanese films that were produced outside the studios. These films were shown at the movie theatres owned by the Art Theatre Guild. From 1967 onward ATG started to produce their own films and became the most important producer of Japanese independent movies. Until the mid-1980s ATG strongly influenced the whole of Japanese cinema.

Independent cinema in Japan

Independent cinema, however, did not start in the 1960s. The first independent productions (dokuritsu puro) appeared in the 1920s when directors as well as actors left the studios in order to establish their own companies. Theirs was a deliberate reaction against the studio system that had developed since the 1910s and in this the dokuritsu puro differed from the various earlier small production companies. Some became independent for artistic reasons, e.g. Teinosuke Kinugasa, who wanted to direct his ambitious masterpiece A Page of Madness (Kurutta Ippeiji, 1926), one of the most important avant-garde films of all times. Kinugasa would not have been able to realize this project within the studio system. In most cases, however, it was economic considerations, which prompted actors and directors to establish their own companies. The stars who were responsible for most of the studios' income began to demand a share in the profits. Tsumasaburo Bando and Chiezo Kataoka, the major stars of the popular jidai geki, were able to make more money by leaving the studio. Also, they were no longer dependent on a single employer; they now had choice. This brought them higher salaries and greater freedom, but they still depended on the studios, just as the studios were dependent on the popularity of their stars.

Because of increasing centralization many of these independent production companies were supplanted by the big studios in the 1930s. In 1941, the government ordered all movie companies to merge into the three blocks Shochiku, Toho and the newly established Daiei. Thus the first phase of independent productions came to an end.

In the late 1940s there was a second wave of independent production companies, this time for political reasons. After the war, the studios had to conform to the new demands of the allied occupation forces headed by the United States. They also had to deal with the trade unions that were established under the influence of the allies. The studios were under an enormous amount of pressure from these trade unions. Toho, for instance, was shaken by three major strikes, which almost ruined the studio. Later on, during the so-called Red Purge, Toho and the other studios took their revenge by firing undesirable, i.e. left-wing artists.

The outbreak of the Cold War led to a change in occupation policies and to the suppression of the communist-dominated trade unions. In 1950, members and sympathisers of the Communist Party were removed first from official positions and later from private companies by order of General MacArthur. Altogether there were 336 people in the film industry who lost their jobs in this way. Many left-wing directors such as Satsuo Yamamoto, Tadashi Imai and Kaneto Shindo therefore established their own production companies. With the backing of the trade unions as well as the Communist Party they made films about the proletariat and the citizens' struggle against the bureaucracy and the state in which they exposed the contradictions within Japanese post-war society. This second phase of independent cinema did not last very long, however. The studios soon regained their old strength and quickly got rid of the competition.

In the 1920s, when studios had suffered from a lack of capital, as well as in the late 1940s independent production companies profited from the big studios' weakness. They successfully occupied certain gaps in the market, but were often dependent on the studios either as sub-contractors or because they had to fill out their repertoire. Because of the block-booking system the studios had to constantly supply their cinemas with new films. If they could not keep up on their own, they had independently produced films to fall back on. However, in the 1950s, when the studios flourished, there was hardly room for independent films. In 1959, when the Japanese studio system reached its zenith, there were no independent productions at all.

The 1950s are generally regarded as the Golden Age of Japanese cinema. They were certainly the Golden Age of the Japanese studios. After the painful adjustments of the post-war period, Toho, Shintoho, Shochiku, Daiei, Nikkatsu and the newly established Toei dominated not only film production but, as they were distributors and exhibitors at the same time, all other levels of the movie market.

In addition to radio the movies were a favourite pastime. Many people went every week to see the new double feature. At the end of the 1950s Japanese cinema reached its zenith. In 1958, 1.13 billion people went to the movies, and in 1960 production reached an all-time high with 547 new films. In order to satisfy the ever-increasing demand for new material, many young assistant directors were permitted by the studios to direct their own films and thus had the opportunity to try out new ideas. Shochiku in particular had several talented assistant directors who debuted in this way: Nagisa Oshima made A Town of Love and Hope (Ai to Kibo no Machi) in 1959, one year later Masahiro Shinoda's One Way Ticket for Love (Koi no Katamichi Kippu) and Yoshishige (later Kiju) Yoshida's Good-for-Nothing (Rokudenashi) set a new course. They were called "Shochiku Nouvelle Vague" after the French Nouvelle Vague. The difference between them was that the Japanese Nouvelle Vague was essentially a product of the studios (Shohei Imamura, who is generally, at least in the West, associated with the Japanese Nouvelle Vague, worked for Nikkatsu), whereas the French Nouvelle Vague like many other innovative movements in Europe established itself outside the studio system.

Oshima, Yoshida and Shinoda soon hit a snag where the studio was concerned. They simply were not allowed the freedom they needed to develop their ideas. As early as 1960, Oshima left Shochiku, when the studio pulled back his fourth film Night and Fog in Japan (Nihon no Yoru to Kiri) after only four days in the cinemas. Yoshida left the studio in 1964 after his film Escape from Japan (Nihon Dasshutsu) had been severely cut by Shochiku (before that, one of his projects had been cancelled and he'd had to go back to work as assistant director for a while). Finally, in 1965, Shinoda left Shochiku after 12 films. For the directors of the Shochiku Nouvelle Vague and others who later followed their example, escaping from the assembly line production system of the studios was an important step in order to demonstrate their independence and individuality.

Despite the friction between the directors and the studio (they did not always settle amicably, especially in the case of Oshima), the break was not complete. Even after they had parted company, many of their films were still distributed by Shochiku. Only after finding a new distributor and later a new producer in the Art Theatre Guild could the Nouvelle Vague directors completely disengage themselves from Shochiku. What becomes obvious here is the fact (typically Japanese and still valid today) that even independent productions continue to a certain extent (if it's not the production, at least, in this case, it's the distribution) to depend on the big studios.

In some respects this is also true for the Art Theatre Guild, which in the mid-1960s became the artistic home of the directors of the Japanese Nouvelle Vague. Ultimately, even the Art Theatre Guild was dependent on Toho, its main financier and one of its initiators. ATG did not really compete with Toho and the other studios, they rather complemented each other. Experiments made possible by ATG were unthinkable within the structure of the studio system, especially in times of dwindling attendance and decreasing revenue. The studios preferred to let others worry about the unprofitable auteur films and concentrate instead on the rather more lucrative genre cinema. To a certain extent, however, the studios supported independent productions such as ATG's because their experiments were considered an important source of innovation. From 1968 onwards, ATG was the major experimental laboratory of Japanese film. Soon they began to act as talent scouts as well, so the studios had new talents to fall back on whenever they needed it.

Until the 1950s there had been no real conflict between artistic claim and commercial value (almost all of Ozu's films, for instance, were big hits at the box office), but during the 1960s commercial considerations became increasingly important. This was partly the result of a change in the audience, which became more and more varied and eventually split up into little groups of people with specified interests and predilections which could not be satisfied by one single film.

In the 1960s, television replaced the cinema as the favourite form of entertainment. Because of this and the rapidly developing leisure industry cinema attendance declined drastically. This had its effect not only on the studios but mainly on exhibitors, who were bound to the studios by exclusive contracts. Smaller theatres in particular were no longer able or even willing in view of decreasing profits to pay for expensive studio productions. They started looking for cheaper alternatives and found them in low-budget films of independent companies, which mushroomed in the early 1960s. As these films provided a topic which was still taboo in the studios, i.e. sex, they quickly found their audience and brought handsome profits to cinema owners as well as small production companies at the expense of the studios. The number of these so-called "eroductions" increased from just 15 in 1962 to 98 in 1965 and 207 in 1966. In 1968, there were 265 eroductions, for the first time outstripping studio production.

By the late 1960s, these independent eroductions were called pink eiga, the term that is still used today. Like studio productions they were made primarily for commercial reasons, but they were not restricted as far as content and plot were concerned. Therefore, many directors used them as far as the low budgets permitted to make extremely individual and analytical movies. Koji Wakamatsu, Masao Adachi and other radicals turned their pink eiga into political propaganda, others such as Atsushi Yamatoya used them for formal experiments. The manager of the Art Theatre Shinjuku Bunka, Kinshiro Kuzui, is to be thanked for the fact that the films of these directors were made available to a large audience and that they were taken seriously by the critics.

In the 1970s, the big studios started to encroach upon the lucrative sexploitation market. Nikkatsu changed its entire production to Roman Porno in 1971, but pink eiga did not lose their importance. On the contrary, as most studios (except Nikkatsu) stopped employing new assistant directors in order to save money, aspiring directors found their chances for a career severely limited. They had to look for alternatives and found them in directing pink eiga as they provided a way of getting into the movie business. Yojiro Takita, Masayuki Suo, Kiyoshi Kurosawa and other successful directors started out like this. Even directors who are not usually associated with pink eiga, like for instance Kohei Oguri, Kazuo Hara or Nobuhiro Suwa, worked at the beginning of their careers as assistant directors in this genre that is so essential to Japanese film.

Many of them had made 8mm-films as early as high school or university. Student and amateur films became an important aspect of the cinematic landscape of the 1970s. These activities did not start in the 1970s, but go back to the late 1950s. The film club of Nihon University played a decisive role in this. Motoharu Jonouchi, Masao Adachi and Katsumi Hirano later became important representatives of Japanese experimental film. If the term "independent" fits any aspect of movie industry of the 1960s at all it has to be experimental films. Here ATG played a doubly decisive role. On the one hand, apart from Hiroshi Teshigahara's Sogetsu Art Center, ATG's Shinjuku Bunka Cinema and its underground theater Sasori-za had become the most important venue where experimental film was concerned. On the other hand, ATG gave several experimental directors the chance to make feature films, among them Toshio Matsumoto, Nobuhiko Obayashi and Yoichi Takabayashi (the stars of the amateur 8mm-scene), and Shuji Terayama, the famous playwright and leading figure of the Japanese avant-garde theatre. ATG enabled them to direct groundbreaking films, some of them masterpieces of Japanese avant-garde cinema.

Matsumoto had originally directed documentaries, the third important pillar (after pink eiga and experimental and student films) of Japanese independent cinema in the 1960s. The film department of the publishing house Iwanami (established in 1950) played a decisive role, especially with regard to PR films and documentaries. Susumu Hani, Kazuo Kuroki, Noriaki Tsuchimoto, Shinsuke Ogawa and Yoichi Higashi all started out with Iwanami. Ogawa and Tsuchimoto continued to make documentaries and became internationally distinguished directors in their field. Others later moved on to feature films and directed several important movies in the 1970s.

In the 1960s and 1970s the Art Theatre Guild held all the strings as far as Japanese independent cinema was concerned. They united the directors of the Nouvelle Vague who had left the studios, the documentarists of Iwanami Productions, directors of sexploitation movies as well as important representatives of amateur and experimental film. But what exactly was the Art Theatre Guild? In order to answer this question it is necessary to return once more to the "Golden Era" of Japanese cinema.

The Art Theatre Guild

Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon winning the Golden Lion at the Venice film festival in 1951 gave the Japanese movie industry a first glimpse of the international market. The subsequent success of other Japanese films at European festivals impressively demonstrated their strength. Still, film exports could in no way compare to film imports. Foreign movies had always been popular in Japan, but after WW2 their number was limited because of currency regulations, and importers were allocated quotas by the government. As domestic film production increased at the expense of foreign imports, distributors were less willing to take risks. They preferred films that could guarantee commercial success and largely ignored ambitious and "difficult" films.

There were several initiatives that attempted to adjust this imbalance. One was instigated by the group Cinema 57 which had been founded in 1957 by the young directors Hiroshi Teshigahara, Susumu Hani, Zenzo Matsuyama and Yoshiro Kawazu, the critics Masahiro Ogi and Kyushiro Kusakabe, Sadamu Maruo (later director of the National Film Center), Ryuichiro Sakisaka (editor of the art journal Geijutsu Shincho) and Kanzaburo Mushanokoji. Their first project was the film Tokyo 58, which was shown in 1958 at the first festival of experimental film in Brussels. Another project was the formation of the Association of the Japanese Art Theatre Movement (Nihon Ato Shiata Undo no Kai) which aimed at setting up special cinemas for the showing of non-commercial art movies. This association was soon joined by the critic Naoki Togawa, the director Hiromichi Horikawa and the vice-president of Towa, Kashiko Kawakita, who became a driving force of the Japanese art theatre movement.

Before the war, she, together with her husband Nagamasa Kawakita, had imported many important European films to Japan. After the war the Kawakitas were still committed to the ambitious European art cinema. In the mid-1950s Kashiko Kawakita spent two years in Europe, getting acquainted with the art theatre movement, which became international in 1955, as the International Association of European Art Theatres C.I.C.A.E. (Confédération Internationale des Cinémas d'Art et d'Essai) was founded. On returning to Japan she worked towards the establishment of a film library, of an institution similar to the Cinémathèque Française and the British Film Institute and a movie art theatre like the National Film Theatre in London, which had opened in 1957 with Akira Kurosawa's Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jo, 1955).

Kashiko Kawakita and the Japanese Art Theatre Movement were supported by their old friend Iwao Mori, then vice-president of Toho. Mori had started out as a film journalist and had written the first comprehensive study of the American movie business in Japanese. Then he started to write screenplays, became a producer and, in the 1920s, initiated the "Association for the Recommendation of Good Films" (Yoi Eiga o Susumeru Kai). Mori talked Taneo Iseki, the president of Sanwa Kogyo, into supporting them and on 15 November 1961 the Art Theatre Guild of Japan (Nihon Ato Shiata Girudo / ATG) was launched. Taneo Iseki became its first president. In the 1920s, he had edited the programs of the Musashinokan, one of Tokyo's most prestigious first-run cinemas. Later he had worked for Shochiku and P.C.L. (a predecessor of Toho), and in 1946 he had gone into business for himself. He founded the cinema chain Sanwa Kogyo and become an exhibitor. Sanwa Kogyo brought one million yen and a cinema, the Shinjuku Bunka, into the new undertaking. Toho contributed five million yen and five cinemas (the Nichigeki Bunka in Tokyo, the Meiho Bunka in Nagoya, the Kitano Cinema in Osaka, the Toho Meigaza in Fukuoka, and the Koraku Bunka in Sapporo). The cinema operators Eto Rakutenchi, Teatoru Kogyo und OS Kogyo joined in with one million yen respectively and four cinemas (the Sotetsu Bunka in Yokohama, the Korakuen Art Theatre in Tokyo, the Kyoto Asahi Kaikan in Kyoto and the Sky Cinema in Kobe). Thus, the Art Theatre Guild had ten cinemas in the whole of Japan at their disposal.

In April 1962, ATG started their program with Mother Joan of the Angels (Matka Joanna od Aniolow, 1961) by Polish director Jerzy Kawalerowicz. The repertoire was chosen by a committee of mainly film critics. At the time of its founding these were Tadashi Iijima, Shinbi Iida, Jun Izawa, Jinichi Uekusa, Chiyota Shimizu, Naoki Togawa, Keinosuke Nanbu and Juzaburo Futaba. Most of them had published in the programs of the Musashinokan and knew Taneo Iseki from that time. Further members of the committee were Masahiro Ogi, Susumu Hani, Zenzo Matsuyama, Ryuichiro Sakisaka, Kyushiro Kusakabe, Sadamu Maruo and Kashiko Kawakita from the Association of the Japanese Art Theatre Movement. Hiroshi Teshigahara was not included as he had already started work on Pitfall (Otoshiana, 1962), which was later distributed by ATG.

Setting up an independent committee was a radically new approach. As most of its members were film critics the films were chosen with artistic instead of commercial considerations in mind. At first, the films distributed by ATG were predominantly European productions, mostly contemporary, but also some classics which had never been shown in Japan such as the films of Sergei Eisenstein and Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941). Apart from masterpieces by Bergman, Cocteau, Antonioni, Buñuel, Fellini, Resnais and other established directors, ATG introduced several less famous names such as young Polish directors (Kawalerowicz, Wajda, Munk), the French Nouvelle Vague (Godard, Truffaut, also Agnès Varda and Bertrand Blier), Soviet filmmakers (Kalatozov, Schweitzer, Kheifits, Parajanov), young rebels like John Cassavetes and Tony Richardson, and, finally, Satyajit Ray and Glauber Rocha. ATG thus played a vital role in the creation of a new consciousness of film history in Japan.

Apart from foreign movies, ATG also acted as distributor for several independently produced Japanese films such as Teshigahara's Pitfall as well as films by Kaneto Shindo, Susumu Hani, Kazuo Kuroki, Yoshishige Yoshida, Nagisa Oshima and Akio Jissoji, whose later films ATG also produced.

Not only the method of selecting the films was new, the way in which they were presented was novel, too. One of ATG's basic rules was to show each film for at least a month, irrespective of attendance. In the 1960s, the repertoire was usually changed weekly, and a four-week run was exceptional even for box-office hits. ATG's flagship was the Art Theatre Shinjuku Bunka in Tokyo, which was managed by Kinshiro Kuzui who remained pivotal until the mid-1970s. The Shinjuku Bunka had been built in 1937 as a contract cinema of Toho. Kuzui readapted it according to his own plans and created a completely new type of cinema. The whole cinema was painted a dark shade of grey, bills and posters and any other kind of flashy advertising were banished, there were only afternoon shows (most cinemas opened in the morning), the seats were spacious and comfortable, and the audience could not simply come and go during a performance like they did in the other cinemas. The foyer acted as a gallery where well-known painters and illustrators exhibited their work. ATG posters were often designed by famous artists and were utterly different from traditional movie bills.

In the evenings, after the movies were over, Kuzui, who was also interested in modern theatre, started to organize theatrical performances. He benefited from the fact that several new troupes had split off from established ensembles in the early 1960s and were now looking for suitable venues. The first stage performance in the Shinjuku Bunka was the Japanese premiere of Edward Albee's The Zoo Story on June 1, 1963, followed by more plays by Albee, Tennesse Williams, Samuel Becket, Harold Pinter, LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), Tankret Dorst, Jean Genet, Edward Bond, Barbara Garson, and other contemporary foreign dramatists. Many of these were Japanese debuts. Apart from these, the Shinjuku Bunka also put on many plays by leading Japanese writers, among them Shuji Terayama, Juro Kara, Minoru Betsuyaku, Kunio Shimizu, and Yukio Mishima. Thus it was not only one of the most important cinemas in Japan but also (despite the tiny stage) one of the major venues for contemporary drama.

Kuzui envisaged an expansion of the Shinjuku Bunka into a comprehensive art theatre. Together with ATG productions and in special programs he presented experimental short films, among them works by Takahiko Iimura, Katsuhiko Tomita, Donald Richie, Nobuhiko Obayashi (whose films were shown publicly for the first time) and Masao Adachi's Sain (1963), which was shown as the first "Night Road Show" in 1965. The Shinjuku Bunka was the first cinema in Japan that had regular shows later than 9pm, a practice that was later adopted by many small theatres.

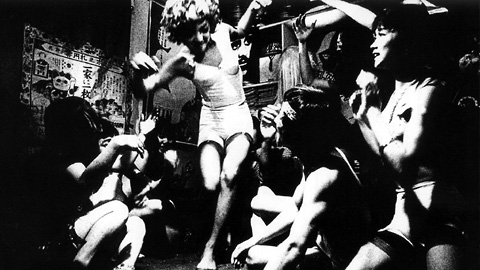

In order to present even 8mm or 16mm films in the best possible quality (the screen of the Shinjuku Bunka was too big for these formats), in the basement of the Shinjuku Bunka Kuzui had a small theatre built for film and theatrical performances, concerts, and other events. The Sasori-za was inaugurated on June 10, 1967 with a performance by the flamenco dancer Yoko Komatsubara. In August 1967, the first film that was shown there was Masao Adachi's Galaxy (Gingakei, 1967). It was Yukio Mishima who was responsible for the name Sasori-za (Theatre Scorpio), a tribute to Kenneth Anger's film Scorpio Rising which was shown at the Shinjuku Bunka before. The Sasori-za was the first underground theatre in Japan, others soon followed. It was a center of experimental drama and experimental film (together with Teshigahara's Sogetsu Art Center) as well as a popular meeting place for all kinds of artists. There were movie and theater performances, concerts and recitals, happenings, and dance performances by Tatsumi Hijikata, the pioneer of butoh dance. The Sasori-za was one of the major centers of the Japanese avant-garde and set an example for many other underground theatres.

Five days after the opening of the Sasori-za ATG released Shohei Imamura's controversial documentary A Man Vanishes (Ningen Johatsu, 1967). This was the first film that ATG also co-produced. The idea of not only distributing but actually producing films had taken shape in 1965 with Mishima's Patriotism (Yukoku), the only film he directed, which was screened with great success at the Shinjuku Bunka. As the film is merely 28 minutes long, it was shown as a double feature with Buñuel's Diary of a Chambermaid (Le journal d'une femme de chambre, 1966). A little later, Oshima's Yunbogi's Diary (Yunbogi no Nikki, 1965) was similarly successful. These triumphs provided the encouragement to start producing films.

Calculating the profits of their previous films, ATG decided that in case of a budget of approximately 10 million yen (then less than US$28.000) they should be able to cover the production costs. What eventually facilitated the decision to expand into production was the liberalization of the import market. In 1964, the official limit for importing foreign movies was abolished. So was the allocation of quotas which had determined the number of films per distributor. One result of this liberalization was a rise in distribution costs so that it became increasingly uneconomical to import foreign films. ATG decided that it would be more profitable to produce its own movies.

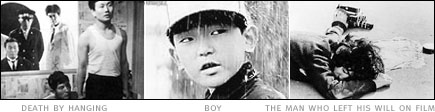

In the case of Imamura's A Man Vanishes ATG had not been involved in the planning stage but had only helped out in the final phase of production. The first film planned and produced by ATG was Oshima's Death by Hanging (Koshikei), which was released in February 1968. Production costs were split between ATG and Oshima's production company Sozosha. Later productions followed the same pattern. Films were financed by ATG and the director's company in equal shares. Compared to those of the studios, feature film budgets were quite modest. Even though the estimated 10 million yen were hardly ever enough, ATG's films were often referred to as "10 million yen movies" (issenmanen eiga).

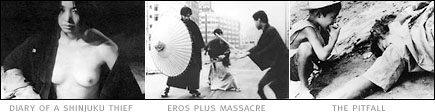

Projects were chosen by an independent planning committee of film critics. In the beginning, the directors of the Japanese Nouvelle Vague were at the center of ATG's production activities. Many of their major works were made in collaboration with ATG: Death by Hanging, Boy (Shonen, 1969), The Man Who Left His Will On Film (Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa, 1969), The Ceremony (Gishiki, 1971), and Little Summer Sister (Natsu no Imoto, 1973) by Oshima, Heroic Purgatory (Rengoku Eroika, 1970) and Coup d'Etat (Kaigenrei, 1973) by Yoshishige Yoshida, Double Suicide (Shinju Ten no Amijima, 1969) and Himiko (1974) by Masahiro Shinoda, as well as The Inferno of First Love (Hatsukoi Jigokuhen, 1968) and Morning Schedule (Gozenchu no Jikanwari, 1972) by Susumu Hani. Furthermore, ATG distributed several films by Oshima (Manual of Ninja Martial Arts / Ninja Bugeicho, 1967; Diary of a Shinjuku Thief / Shinjuku Dorobo Nikki, 1968) and Yoshida (Farewell to the Summer Light / Saraba Natsu no Hikari, 1968; Eros Plus Massacre / Erosu + Gyakusatsu, 1970; Confessions among Actresses / Kokuhakuteki Joyuron, 1971). ATG's importance for the Japanese Nouvelle Vague can hardly be exaggerated.

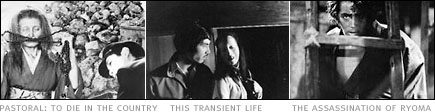

At the same time, ATG gave several experimental directors the chance to realize their extremely individual fantasies, most importantly Toshio Matsumoto (Funeral Procession of Roses / Bara no Soretsu, 1969; The Pandemonium / Shura, 1971) and Shuji Terayama (Throw Away the Books, Let's Go into the Streets / Sho o Suteyo, Machi e Deyo, 1971; Pastoral: To Die in the Country / Den'en ni Shisu, 1974; Farewell to the Ark / Saraba Hakobune, 1984). Akio Jissoji and Kazuo Kuroki also were very experimental in their approach; in the 1970s they became ATG's leading directors. Jissoji had started out in television and had only directed one short film, When Twilight Draws Near (Yoiyami Semareba, 1969), which ATG had distributed and shown as a double feature together with Oshima's Diary of a Shinjuku Thief. This Transient Life (Mujo, 1970) was the first of four films which Jissoji realized together with ATG. This masterpiece is one of the very rare successful cinematic representations of Buddhist philosophy and has undeservedly fallen into oblivion even though it won the Grand Prix at Locarno in 1970.

Apart from Akio Jissoji, there is Kazuo Kuroki, another director who still needs to be discovered in the West. ATG distributed his early masterpiece Silence Has No Wings (Tobenai Chinmoku) in 1966 and produced his later feature films The Assassination of Ryoma (Ryoma Ansatsu, 1974), Preparations for the Festival (Matsuri no Junbi, 1975), and Lost Love (Genshiryoku Senso, 1978). Other directors, many of whom worked for a studio, got the chance to finally realize their dream projects which they could not do within the structure of the studios: Kihachi Okamoto, Kon Ichikawa, Ko Nakahira, Kei Kumai, Yasuzo Masumura, Koichi Saito, Sadao Nakajima, and Nobuo Nakagawa. ATG also produced several films of Kaneto Shindo, the veteran of Japanese independent film.

The early films of ATG were determined by the explosive political climate of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The highlight of their political films is Koji Wakamatsu's Ecstasy of the Angels (Tenshi no Kokotsu), which was, in 1971, closer to the events of the day than any other film. Ecstasy of the Angels is based on a screenplay by Masao Adachi, who later defected to Lebanon and became a member of the Japanese Red Army. The film anticipated the terrorism of the left-wing guerrilla in an almost prophetic manner and thus made for one of the biggest scandals in the history of ATG.

After 1972, political topics retreated into the background. It is possible to identify two strands of escapism in ATG's films: there is the escape from urban to more rural settings and the escape into the past. Typical films are Koichi Saito's Tsugaru Folk Song (Tsugaru Jongara-Bushi, 1973) and Kon Ichikawa's The Wanderers (Matatabi, 1973). Both of them were made by studio directors, which indicates a development towards increasingly orthodox films. ATG, admittedly, continued to co-operate with experimental directors such as Yoichi Takabayashi and, later, Nobuhiko Obayashi, but the films made after 1973 were much less radical than the earlier films. The main reason, apart from the general spirit of the age, was the closing of the Shinjuku Bunka in 1974. ATG thus lost one of its most important assets.

Most of ATG's other cinemas had already bailed out earlier. The profits were simply not large enough, nor were the people in charge sufficiently farsighted. The last film to be shown at the Shinjuku Bunka before it was closed was Terayama's Pastoral: To Die in the Country. Thus ended the heyday of the Art Theatre Guild. Kinshiro Kuzui stayed on for some time as an independent producer, but his function as main producer was taken over by Shosuke Taga, who had been responsible for editing the programs ever since the beginning of ATG. Toho's reopening of the newly refurbished Shinjuku Bunka with Just Jaeckin's Emmanuelle must have been painful for Kuzui, who embodied the essence of ATG like nobody else, even though he had remained an employee of Sanwa Kogyo and had never officially been a member of ATG.

Sexploitation films kept many people afloat in Japan as well, as it was the only market that actually boomed. Still, many directors tried to break out of this quandary and ATG gave Chusei Sone, Seiichiro Yamaguchi, Tatsumi Kumashiro, Koyu Ohara, Kichitaro Negishi, Toshiharu Ikeda, Banmei Takahashi, Kazuyuki Izutsu, and other Roman Porno and pink eiga directors the chance to establish themselves outside this field.

Among the directors who left Nikkatsu was Kazuhiko Hasegawa, who had debuted with ATG to great acclaim in 1976 with Young Murderer (Seishun no Satsujinsha). This film marked the beginning of a new development in the history of ATG: the promotion of young directors who had not yet gained a lot of experience in the making of feature films. In 1979 producer Shiro Sasaki replaced Taneo Iseki as president of ATG. He belonged to a different generation, and this is reflected in the new films. Yoshimitsu Morita, Sogo Ishii, Shunichi Nagasaki and other major representatives of the independent cinema of the 1980s worked with ATG, but they were not tied to ATG in the same way their colleagues were a decade or two earlier. New independent production and distribution companies as well as cinemas took over from ATG and established themselves outside the studios, which largely gave up producing and became mere distributors and cinema operators.

When ATG was founded in the 1960s, Japanese cinema was still dominated by the studios even though they were already on their way out. ATG was the most important producer and distributor outside the studio world and decisively shaped the development of Japanese cinema. When the studios virtually stopped producing films and new companies filled the gap, the Art Theatre Guild could retire with a clear conscience and surrender the field to others who followed and expanded their policy of quality films. The spirit of ATG lives on in the independent cinema of today.

NB: This essay originally appeared, in German, in Art Theatre Guild: Unabhängiges Japanisches Kino 1962 - 1984, the bilingual (English/German) catalogue to the ATG retrospective organised by the Viennale and the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna between October 4 and 30, 2003. Roland Domenig curated the retrospective.