Petrel Hotel Blue

- Year

- 2012

- Original title

- Kaien Hoteru Buru

- Japanese title

- 海燕ホテル・ブルー

- Director

- Cast

- Running time

- 84 minutes

- Published

- 20 May 2013

by Aaron Mannino

One of Koji Wakamatsu’s final cinematic works, Petrel Hotel Blue had its world premiere at New York’s Japan Society in 2012 as part of the standout Love Will Tear Us Apart season. Curator Samuel Jamier had pieced together a cross-cultural narrative of emotional/existential malaise through the relational cinemas of Korea and Japan, among which Ki-duk Kim and Wakamatsu were featured generously. With no additional screenings for Petrel Hotel Blue on the horizon, and such proximity to Wakamatsu’s untimely passing, it seems pertinent to visit upon this strange little film.

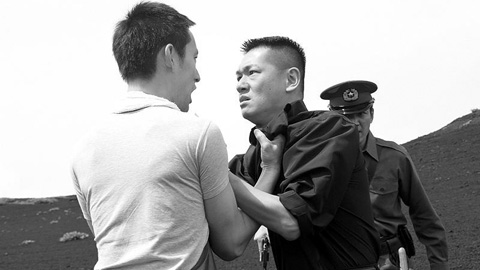

Based upon a novel of the same name by Yoichi Funado, Petrel Hotel Blue is about friends Yoji (Hirosue), Yukio (Jibiki), and Kohei (Uda) attempting a vehicular robbery. Yoji never shows, Kohei flakes at the scene, and Yukio takes the fall for the failed endeavor. Years later, Yukio is freed from prison and enacts a revenge plot against Yoji. From this point, one might anticipate an unsympathetic vengeance story consistent with the Asian arthouse of the past decade, but with Wakamatsu the intrigue is a pretense. Yukio traces Yoji to the isolated island hotel that he now manages with a sensuous and silent woman named Rika (Katayama). From this desolate environ, literally a kind of primordial Nowhere replete with ominous black volcanic sand, reality quickly deteriorates. Tensions and rivalries rise, things are said, people are killed, dreams are inhabited, space and time crumble. The catalyst of this degeneration, and the cause of the Yoji’s absence all those years ago is one and the same: Rika. And she has curves that will make you blush.

Petrel Hotel Blue seeds deeply over time. It correlates to something familiar and distinctly Japanese, as well as to Wakamatsu’s own legacy. Wakamatsu’s techniques of structure, editing, color manipulation, use of dissolves, slow-motion, and even shooting in HD, are basic in their aim to disorient the viewer and to render a saturated reality. On a material level, Wakamatsu doesn’t do anything with Petrel that can’t be found in student films across the globe, but his mastery is evident in the severity and purity of his execution. Touches of noir, psychological horror, folklore, and even black comedy blend into a unique creature, enhanced by the immensely tactile resolution of High Definition. Perhaps as a virtue of the HD aesthetic, and the ironic artificiality it lends to subjects, his characters by contrast have an internal vitality and are all the more victims of Wakamatsu’s manipulations, which engender spontaneity of character by contrast of very rigidly cinematographic, architectural, and structural conventions. The result is an emphasis of the human.

With Petrel Hotel Blue, Wakamatsu tackles a staple Japanese theme, man’s weakness in the face of female sexuality. Here it is reminiscent of author Kenji Nakagami’s short story A Tale Of A Demon (Oni no Hanashi, 1981), which concerns a demon in the guise of a woman who seduces an arrogant demon-slayer swordsman away from his trade into solicitude, unaware that she is in fact the great demon he had set out to slay - the very definition of a man-eater. Wakamatsu and Nakagami could easily stand on the same provocative platform, as they share in a brutality of matter-of-factness applied to metaphysical content. Shohei Imamura’s Under the Blossoming Cherry Trees could be drawn into the same fold, with a narrative that verges into an absurd degree of debauchery and violence in its protagonist’s pursuit of sexual possession of a demon-woman, which, like in Wakamatsu’s film is inversely the case.

Petrel Hotel Blue is most interesting where it concerns the vixen, the female “demon” Rika, even though she seems a periphery. Like Sozaburo Kano, Ryuhei Matsuda’s character in Nagisa Oshima’s Gohatto – where an idol of (male) physical beauty and emotional disaffection is introduced into the sanctity of samurai code – Rika in Wakamatsu’s film displaces the loyalty amongst thieves. Rika and Sozaburo are indeed both objects, but Rika is the more complete distillation, having only two lines in the entire film, and barely so much as blinking the entire time. Rika is a stunning surface, a blank empty form with glistening supple lips and ample breasts, who smokes and stares out to sea, made all the more alluring to her admirers for her utter vacancy. Her emptiness draws out the worst compulsions in men like a vacuum. One might also compare Rika to the titular character of Kim Ki-young’s The Housemaid (1960), as an equal and opposite. The latter manipulates actively and the former passively in silence, but the fallout that radiates from them is the same. The camera deliberately sexualizes Rika with its gaze (yet there is virtually no sex in the film) and makes her into an object amid the fever of attraction paid her. Rika’s magnetism is death’s magnetism, but the natures of the men in her orbit are complicit in projecting their desires and fears onto her canvas. Wakamatsu abstracts Rika with hypnotic slow motion, rumbling noises one might expect of David Lynch, color saturations, disappearances and reappearances, which make her own nature both ambiguous and unambiguous.

It is of some interest to draw on Wakamatsu’s previous work, United Red Army, when considering Petrel Hotel Blue, which is a reimaging of the general idea that the occupation of nowhere that can either concretize or fracture one’s perceptions and assumptions of reality and identity. Petrel, however, exists in a spectrum entirely removed from politics or socially conscious reflection. More contemplative and abstract, Petrel is an exercise in the primordial, but is equally the bad dream that United Red Army was.