Seventh Code

- Year

- 2014

- Original title

- Sebunsukodo

- Japanese title

- セブンスコード

- Director

- Cast

- Running time

- 60 minutes

- Published

- 9 March 2015

by Kohei Usuda

At first glance, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s hour-long Seventh Code, made as a vehicle for the 23-year-old J-pop idol Atsuko Maeda to accompany the release of her single of the same name, might not seem like the work of one of contemporary cinema’s most consistently brilliant auteurs, especially coming after 2012’s ambitious four-and-a-half-hour epic Penance. Yet Seventh Code is by no means "minor" or "totally inconsequential," which is how Variety’s Jay Weissberg and Dan Fainaru of Screen International respectively described it. On the contrary, its formal boldness is reminiscent of another "idol movie," Sailor Suit and Machine Gun (1981), Shinji Somai’s popular classic starring the teenage singer-actress Hiroko Yakushimaru in the role of a naïve high school girl who finds herself spearheading her father’s yakuza clan in the wake of his death – a film notable for its extraordinary long takes and rigorous formalism (if not for its ludicrous plotline).

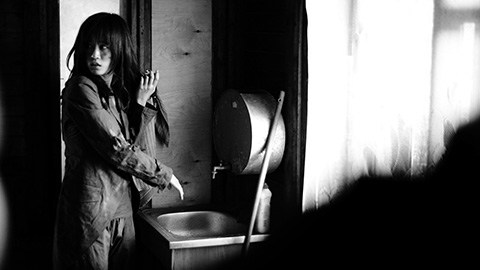

Kurosawa’s first foray into the idol movie genre is also the Kobe-born writer-director’s first film to be shot outside his native country. The story takes place in the backdrop of the desolate landscape of Vladivostok, Russia’s eastern port city situated on the Sea of Japan near the borders of China and North Korea. Out of nowhere, a young Japanese tourist in the form of Atsuko Maeda enters the picture, dragging her stocky, wheeled suitcase and desperately seeking a mysterious Japanese businessman by the name of Matsunaga (Ryohei Suzuki) who purportedly plies his trade in this part of Russia and with whom she has supposedly spent a night in Tokyo’s Roppongi district.

Maeda arrives suddenly and unannounced only to get mixed up in a murky international conspiracy concerning a tug-of-war for a priceless nuclear component called "Krypton," involving the aforementioned Japanese businessman, a redhead femme fatale, a handful of Russian mafia, as well as an expat Japanese chief (Hiroshi Yamamoto) and his Chinese girlfriend (Aissy), who come to Maeda’s rescue in what amounts to a plot every bit as implausible as that of Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955).

With Seventh Code, Kurosawa yet again confirms himself within his domestic cinema as the least "Japanese" of all filmmakers working today. Indeed, with rare exceptions such as his Ozu-esque family drama Tokyo Sonata (2008), which shows how one suburban household in Tokyo unravels due to the economic recession that deeply stagnated the country’s economy, Kurosawa’s cinema includes few tell-tale signs indicating “Japaneseness” (notwithstanding his international reputation as master of J-horror movies), to the extent that one wonders if it was ever necessary for him to film in Japan at all.

In fact, rather than tracing the rich heritage of Japanese cinema, Kurosawa’s referential models have primarily been American genre pictures, having grown up avidly watching the action movies of Don Siegel, Richard Fleischer, Sam Peckinpah, et al. In film after film, he has extensively emulated the emblematic formulas of American genre movies, as is evident in the slasher horror The Guard from Underground (1992), the slapstick action-comedy series Suit Yourself or Shoot Yourself (1995-96), the psycho thriller Cure (1997), the neo-noir revenge sagas Serpent’s Path and Eyes of the Spider (both 1998), the detective story Charisma (1999), and the cyber thriller Pulse (2001), to cite but a few examples. Even in the case of above-mentioned Tokyo Sonata – which makes allusions to Ozu’s Depression-era silent drama Tokyo Chorus (1931) (both concern the struggles experienced by a laid-off Tokyo salaryman) – Kurosawa brushes aside conventions by, for example, having the family’s eldest son enlist in the U.S. Army to fight in the Iraq war. Although Tokyo Sonata tells the story of an ordinary family living in one corner of the Japanese capital, its concerns are universal in nature in that the film deals with the leading symptoms of the current global malaise, from the U.S.-led “war on terror” to the economic recession affecting middle-class households worldwide.

In the case of Seventh Code, Kurosawa disengages himself from his home turf to take full advantage of Vladivostok’s geographical specificity as a borderless and lawless backwater in Russia’s Far East. In so doing he has truly made a mukokuseki eiga – a subgenre of action movies produced by Nikkatsu Studios in the 1950s and 60s – the term translates as "films without nationality." The multinational, nomadic characters in Seventh Code all speak in foreign tongues, mostly English with smatterings of Russian, Chinese-accented Japanese and Japanese-accented Russian.

Well before Vladivostok’s Eurasian setting in his latest film, Kurosawa had always had a penchant for bleak, decaying, barren urban environs. Those are the settings of nondescript wastelands that this filmmaker has customarily favoured, evident in the setting of the toxic forest outside of Tokyo in Charisma, where Koji Yakusho’s detective, on a leave of absence, finds himself in the midst of a power struggle between two opposing parties, a premise strongly reminiscent of Poisonville in Dashiell Hammett’s hardboiled novel Red Harvest. In fact, the Kurosawa-esque nature could hardly be said to constitute a "harmonious" whole, as is the case with the eerie countryside of Loft (2005) haunted by the wrath of a female mummy. Similarly, his vision of Tokyo tends to be strangely depopulated and dystopian, as in Pulse and Retribution (2006). Each of those films ends in an apocalyptic end-of-the-world scenario that suddenly descends on the Japanese capital, not unlike something out of the Hollywood disaster movies of today. (Not surprisingly, Kurosawa names Spielberg’s War of the Worlds [2005] as his favourite film of the past decade.)

"I guess whenever I find some place in ruins or falling apart I know it won’t last," Kurosawa told Midnight Eye’s Tom Mes in 2001. "I know it will be turned into something new very quickly. Even though the location may or may not have some relation to the theme, I find myself filming there just in order to make a record of this wonderful ruined place."

The central theme running through Kurosawa’s cinema is that of "reducing everything to zero, and of starting the world anew," as the director himself defined in an interview with Chuck Stephens in 2001: "In a number of my films, you see cities destroyed, and even hints that the end of civilization is near... I actually see them as just the opposite – as starting again with nothing, and as the beginning of hope." [ 1 ]

It is for this reason that Kurosawa returns, time and again, to the motif of regeneration following on the occurrence of a catastrophic event, such as the reinvigorated tree rising up from the ashes of a forest razed by fire (Charisma); the mutating poisonous jellyfish growing in number and slowly taking over the underbelly of Tokyo’s sewers after the death of its owner (Bright Future [2003]); a family toiling to start over again after dissolution (License to Live [1999], Tokyo Sonata); the survival of a group of traumatized schoolgirls as they grow into adulthood some years after the brutal murder of their friend at the hands of a psychopath (Penance); a father’s vengeful mission to track down and exact revenge on his daughter’s killer (Serpent’s Path, Eyes of the Spider), and so on.

Kurosawa is a storyteller of the first order when he chooses to be, as was skilfully demonstrated in the pair of no-nonsense dramatic masterpieces Bright Future and Tokyo Sonata, not to mention Penance, which expertly employs intricate flashbacks as well as novelistic shifts in perspectives. With Seventh Code, however, he seems merely to "borrow" the typical signifiers associated with the prototypes of Hollywood’s post-Cold War espionage thrillers (in the mold of John Frankenheimer’s Ronin [1998], etc.) – a genre which grew out of the collapse of the Soviet Union and resulting geopolitical shifts (for instance, the presence of villainous Russian mobsters, the plot concerning a nuclear weapon sold on the black market, spies operating as mercenaries, etc.). Here, instead of pretending to maintain any degrees of realism, he opts for an irreverent style that calls to mind Godard’s playful New-Wave reworkings of American B-movies of the 1960s.

Indeed, Kurosawa’s Seventh Code seems like a rough sketch or blueprint for a possible film, not unlike Godard’s Made in USA (1966), with its blatant and conspicuous lack of suspense and refusal to explain the characters’ actions whatsoever. Maeda’s character, for example, remains an ever-changing, indefinable entity from the get-go. The film functions more as an essay on Hollywood’s spy thriller genre than as a conventionally conceived enterprise, as Mark Schilling points out in his review of the film in The Japan Times.

One is tempted to imagine Kurosawa made Seventh Code in response to the collapse of a planned project to be titled "1905," a big-budget Chinese-language production he was slated to direct in 2012, but forced to abandon due to financial and political reasons, the latter having to do with the protracted Sino-Japanese dispute over ownership of the Senkaku Islands, a relation that was further aggravated by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s nationalistic agenda.

In Seventh Code, what emerges in the absence of a plausible plot or verisimilitude is pure filmic action, all of which is staged and executed by Kurosawa with a sure hand. Such elements include the movement of the Japanese businessman’s Soviet-era vintage car being driven across the screen at full tilt, Tarkovsky-like tracking shots of wind sweeping the foliage in the forest, slapstick action in the quintessential Kurosawa setting of a skeletal abandoned factory where the stolen nuclear component is stored, and the tangible white noise of Atsuko Maeda dragging her heavy luggage on Vladivostok’s unevenly paved streets.

Admittedly, these may not serve much dramatic or narrative purpose in terms of the efficiency of storytelling proper, and yet such a view risks missing the point entirely. Like Godard before him, Kurosawa is, if necessary, prepared to shoot an action movie without an exorbitant big budget required of an epic period piece or a bankable movie star in the shape of Tony Leung Chiu-Wai (originally the lead in the ill-fated 1905). In short, the conditions under which Seventh Code was shot are antithetical to those that would have been demanded by the 1905 project.

Shigehiko Hasumi once described Kurosawa as a director who "does not hesitate in hiding his confidence that he’s capable of getting a film made without large-scale movie sets or special effects makeup, by virtue of having started making films following the collapse of the studio system." [ 2 ]

In other words, Kurosawa, who has never known the luxury afforded to those belonging to the bygone era of the studio system (which was in place to enable such masters of the past like Ozu, Mizoguchi and Naruse to produce some of the classic works of Japanese cinema), has conversely specialized, during the mid-1990s, in light-footed flexibility combined with resourceful inventiveness. Early in his career, he regularly churned out low-budget, straight-to-video efforts for the domestic V-Cinema market – averaging an astonishing three films a year – before finally attaining international recognition with Cure in 1997.

In truth, Seventh Code is realized with a minimum of means at his disposal. In effect, the director is saying that all he needs to make a film is an abandoned building somewhere on the outskirts of Vladivostok, coupled with some easily obtainable props like a vintage car, a travel suitcase, a few cases of dynamite, and so on – not forgetting, of course, the onscreen presence of a pokerfaced J-pop idol.

Kurosawa’s Russian adventure heralds a new chapter in his filmmaking practice, echoing the earlier footsteps of Japan’s pioneering feminist poet Akiko Yosano (1878-1942), whose poem "Tabi ni tatsu" (Starting on a Journey) serves as an important inspiration for the film. Yosano’s poem is twice quoted in Seventh Code, first by Aissy’s free-spirited young Chinese woman whom Atsuko Maeda befriends in the course of her sojourn in Vladivostok, then at the end by Maeda’s character herself as she departs the port city for a new life:

"Now, the heaven’s day shall belong to me / Move the golden vehicle forward / Stormy winds sweep from the East / Now, let’s pursue one’s self with good grace."

Yosano’s passionate verses were written in fact in Vladivostok in the spring of 1912 before she embarked on a Trans-Siberian Railway journey bound for Paris, as she breezily and briskly made her way to Europe to follow her husband and fellow decorated poet Tekkan, where the couple would go on to befriend some of the era’s well-known luminaries of the arts.

Her journey to the cultural and artistic capital of Europe mirrors the trajectory taken by Maeda’s heroine in Seventh Code (whose character shares the name of "Akiko") as she auspiciously sets out for Moscow by hitchhiking. This spirited final sequence is interspersed with shots of the former AKB48 member singing her catchy tune produced by Yasushi Akimoto to the rapturous adoration of Kurosawa’s camera.

- [ 1 ]. Chuck Stephens, “Kiyoshi Kurosawa Begins at the End”, The Village Voice, 24 July 2001. http://www.villagevoice.com/2001-07-24/film/kiyoshi-kurosawa-begins-at-the-end/full/

- [ 2 ]. Shigehiko Hasumi, Eiga hokai zenya (Tokyo: Seidosha, 2008), pp. 51-52.